Little Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty)

Reel 1 | Reel 2

Projector 1 snicks off. Projector 2 rattles to life. The screen dissolves into a pallid graininess that filmmakers in later years will call a “leader.” The quivering title card indicates that fifteen years have passed; and the fifteen-year-old princess (played by a twenty-four-year-old ingénue) ascends the spiral staircase of the high tower. Her dimpled face is a mask of genial curiosity, although her eyebrows, which have been plucked away and painstakingly redrawn, give her the air of one perpetually astonished. The door swings inward to reveal an ample chamber.

A withered crone clad in a hooded robe sits before a spinning wheel making thread. The concentrated shaft of arc-light falling from an upper window makes the spindle gleam. The girl’s lips twitch in benign inquiry as she steps in. But no captions appear on the screen, because the ancient actress is so adept at pantomime that we know by her fluid movements that she is explaining to the princess how a spinning wheel operates. She began her career in 1862, when stages were still illuminated by tallow-drips, debuting in title role of Goethe’s Iphigenie auf Tauris

The princess advances, looking askance at the spindle, which she tentatively touches with one fingertip. With lightning-like rapidity, she gasps, flings wide both arms, and collapses to the floor like a stone. Her fall is so hilariously abrupt that a ripple of laughter runs through the audience. The venerable thespian might have offered her a few pointers on dramatic restraint, but she has been replaced by her alter ego, the scorned wise woman, who stands gloatingly over the supine princess, believing her dead.

A montage ensues.

In the kitchen a shrewish cook is upbraiding a back-talking young scullion. Both begin to yawn and fall asleep standing up. Birds perched on the battlements are shown with their heads tucked beneath their wings; but their feathers are unruffled by the wind, betraying this to be a photograph. The king and queen, sitting on their respective thrones (about the only thing monarchs do in films), begin to nod off. The courtiers milling about, and the guards at the door, close their eyes and freeze in whatever position they were in when the princess pricked her finger.

We are back in the high tower, where the sleeping beauty has been miraculously transferred from the floor to a bed (which was nowhere to be seen moments before). A soft light illuminates her unblemished face; but her brow is furrowed in consternation. She has been lying there for hours, because fluctuations in the electric current are causing lightbulbs to pop repeatedly. When the gaffer finally rolls over to a secondary, coal-operated generator, the director calls “Action!” and the shadows of thorn-bearing vines creep across the satin pillow and frame her slumbering head.

The scene closes with an iris shot contracting to a single point; and when it expands again, the castle on the hill looms in the middle distance. The foreground is edged with plywood strips that have been cut up, painted, and arranged into jagged layers forming a three-dimensional wreath of thorns. The director is so pleased with this Expressionistic masterpiece that it is left onscreen for a full minute as a contraption (somewhere in front of the cardboard castle) atomizes glycerin and water to create the illusion of fog.

A placard with gothic Fraktur script provides the prosiest intertitle we have yet encountered in the film:

An enchanted sleep fell upon every living creature in the castle, which itself became surrounded by an impenetrable hedge of thorns. Many forgot that a castle lay beyond this barrier. But legend spoke of a virgin who lay asleep amid the briars, a beautiful girl whom only the most valiant could awaken. Many men tried to penetrate the foliage but died horrible deaths. A hundred years passed. And one day, a prince from a distant land found an opening in the briars.

A handsome young man in a doublet and tights wanders into the scene. He is taken aback when two slats of painted scenery roll apart on castors, exposing an opening into the hedge.

He touches is chin, musing over this phenomenon, as an aged hermit approaches from the opposite side of the screen. The prince gestures to the opening, spurring the hermit to provide a précis of the title card we have just read. As the old man wanders off, he waggles his head, because he senses the prince is precipitous and foolhardy. Wonderingly, the young man waits until the hermit is gone. Taking three deep breaths, he plunges into the hedge.

Two months before filming began, a tenement building in Wedding collapsed, killing ten people. The skeleton of a man were found beneath the cellar floor. A hole at the back of the skull suggested foul play; and a scrap of newspaper stuck in the insole to seal a gap dated to 1857. On reading about this in the Vossische Zeitung, the film director called the Berlin police to ask if he could take possession of the bones once they completed their investigation. Permission was immediately granted, since the matter was not being investigated and the bones had been thrown into a broom closet in the archives.

The director hired an anthropologist to assist the set designer in reconstructing the skeleton into a diorama representing a corpse amid the briars. An oversized papier-mâché thorn was thrust through the hole at the back of the skull, so that it would jut out from between the jaws. The camera lingers on the gory sculpture for many seconds before the prince stops in front of it, placing both hands on his temples and swaying back and forth in a swoon. Faintly, he tells us in a caption that he must go on. But though he is able to do this, we are not.

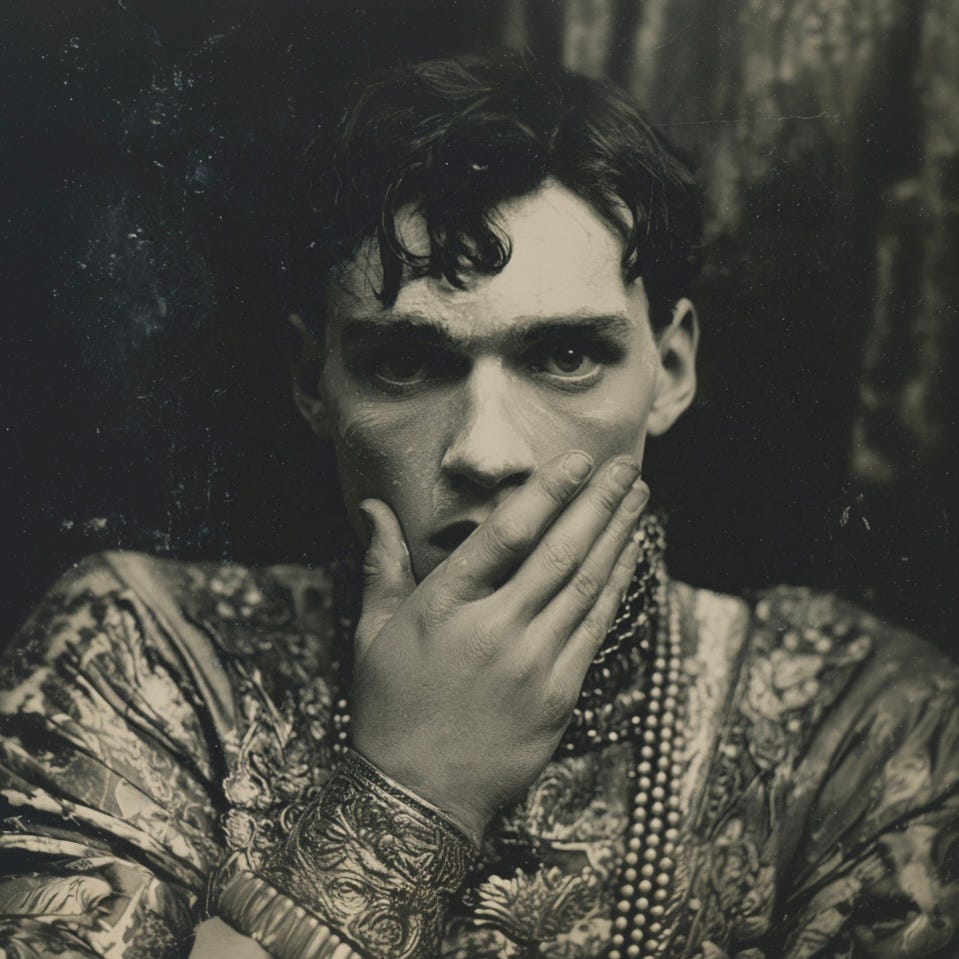

Nitrate film is fragile; and time has obliterated over three minutes of footage, to include the prince’s ascent up a zigzagging ramp leading to the castle’s portcullis. Without warning, we are again in the throne room as the prince contemplates the sleeping royals and their attendants. Since it is impossible for so many actors to stand convincingly immobile as another walks among them, the director focuses the camera on the young man’s face whose lips open, as the most gratuitous line in the film flashes on the screen: “They are all asleep!”

He spasmodically covers his mouth, a gesture the director finds so strange and compelling that he will leave it in the final cut. But what he does not realize is that the prince did this to hide the trickle of blood issuing from his nostrils, because he is a cocaine fiend. He is also a member of the Sturmabteilung (SA), the paramilitary wing of the Nazi party; and last night he and two friends beat to death a female Marxist they found distributing agitprop in the Tiergarten. But his days are numbered and he will die by firing squad on the Night of the Long Knives, accused of procuring athletic teenagers to serve as SA leader Ernst Röhm’s bedfellows.

The prince is now standing at the base of the high tower. He is overcome by an ardor he cannot control. The object of his love lies at the top of the winding staircase. He mounts the bottom step, clutching his chest with his right hand as his left hand claws the wall behind him. When he reaches the top, he enters the room where Little Briar Rose lies asleep on the bed.

Tenderly, he scoops her up into his arms, kissing her lips, which have become the color of blood. Her eyelids flutter open, but there is no life in the lusterless pupils. The prince senses something is amiss. The silent world has been pierced by the rattle of a projector. He is not easily startled, and does not ignominiously release his beloved to let her flop back on the bed. Instead, he twists his upper torso and cradles her in his arms in such a way that they may both see the source of the noise.

There is a pinpoint of light, beneath which scores of faces stare back at them in a darkened gallery. The briars around the bed begin coiling around the prince’s limbs, thorns ripping and tearing into his doublet. For the first time in his life, he hears his own voice when he speaks.

“I feel like I’m dying,” he says. “Or as if my life until now was but a dream.”

“Perhaps both are the case,” Little Briars Rose says, smiling broadly to reveal two rows of fangs. “Kiss me, my love. And I shall awaken you from your sleep.”

Clever revisualisation here, Daniel. Nice atmospheric work. 👏🏻