If you’re joining us just now, follow the snake’s tail to the Prologue or climb a ladder to the Table of Contents.

Chapter 18: “X Marks the Spot Where the Map You’re Holding Can Be Found”

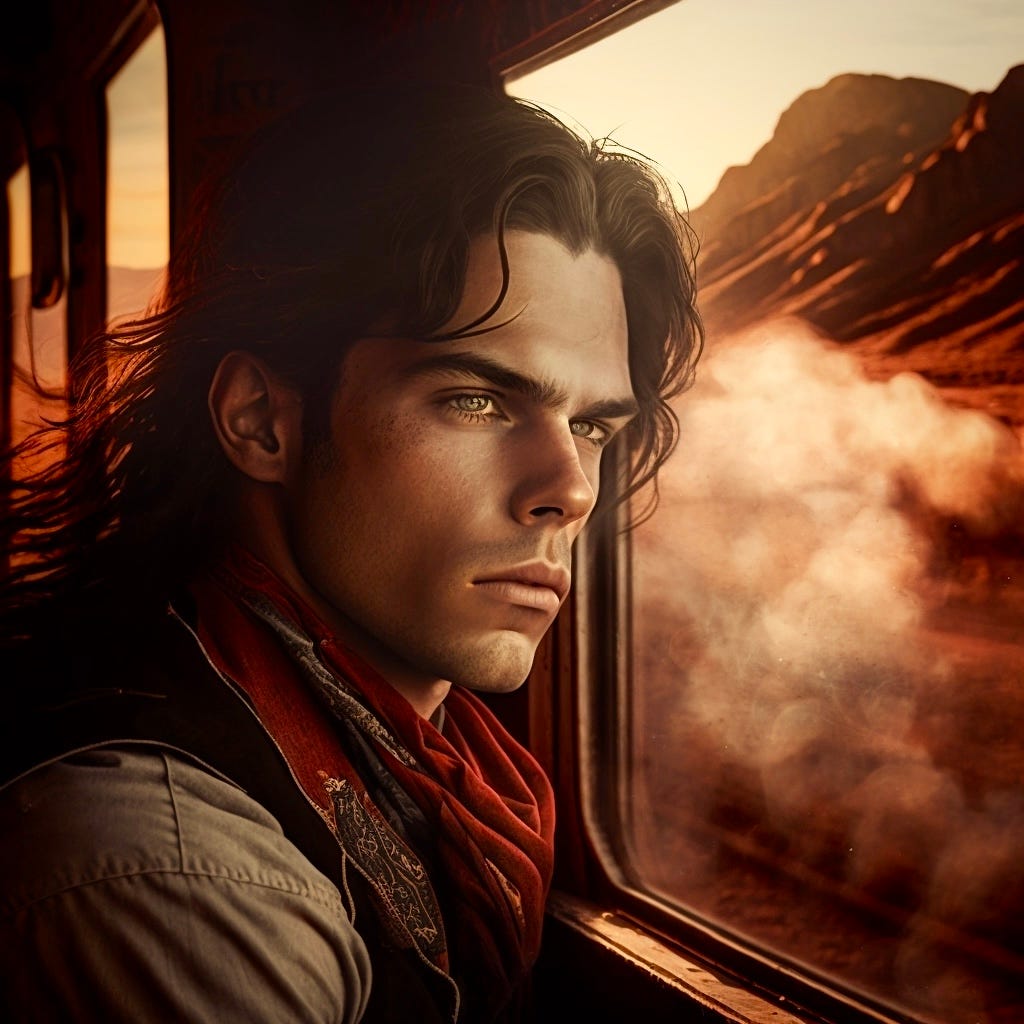

The asthmatic steam engine chuffed through the Arizona desert under a carnelian sky. It was late afternoon and a storm was brewing. Evan, still costumed as a Wild West cowboy, stood at one of the windows because no seats existed on his side of the coach. This should not have been the case since it was a Pullman car. He looked over his shoulder. The other side was banked with plush seats, all of which were occupied by ghostly passengers, the “extras” of America’s favorite sitcom.

The passengers seemed unaware that the middle of the coach was a late 20th century New York subway car, complete with vertical stainless-steel bars and a rubber mat running down the aisle. Straphangers in T-shirts and suits jostled for space as a gravelly voice incoherently mumbled the name of the upcoming stop. Grover Cleveland was evidently still president, according to a newspaper that a man with waxed mustachios was reading in one of the seats by the window.

Evan saw his 7-year-old self sitting next to Madame Blavatsky across from the man reading the newspaper. The boy held a chocolate-colored transistor radio, the speakers of which were cranked up and playing “Ghost Riders in the Sky” by Johnny Cash. As the song droned on, mingling with the noise of the subway speakers’ safety announcement, Evan ungripped the strap he’d been holding onto and grabbed the brass rail under the window.

In the gray clouds hovering over the low mountains, a herd of black fire-snorting cattle climbed a steep embankment. Behind them rode a gang of undead ranchers, led by the Havasupai man who stared down into Evan’s eyes before lifting his hat over his head and crying out for the others to follow him up the jagged acclivity toward an active volcano that was the source of the storm’s thunder. I guess I’m still in Hell, Evan thought.

Niyati stood close by. She wore a fawn-colored traveling dress that made her look like a cross between a prohibitionist and equestrienne. Evan glanced at her irritably and closed his eyes as tightly as he could.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“I’m trying to wake up.”

“Evan, you’re too far into the dream. You can’t wake up now.”

He opened his eyes and turned back to the window. “This is such bullshit.”

“Stop acting like a child.”

“You’re not my mom!”

Niyati laughed because she mistook his remark as a joke. But Evan clicked his tongue and cast an annoyed look at the 7-year-old copy of himself. The child shook its head, as if trying to warn him that he was being a dick.

“Where are we going?” Evan asked.

“I told you 10,000 years ago that I no longer have that strange intuition and foresight I had earlier in your dream. So I don’t know.”

“It makes no fucking sense. One moment, you’re an unborn universe, next moment you’re Niyati—but a Niyati that knows stuff the real Niyati couldn’t possibly know. You’re supposed to be my guide. And you were doing a pretty good job of it right up to the point when we left Wonderland. How can you no longer remember what you knew before?”

“Well, Mister Pouty Britches, do you remember anything from that part of the dream when you were a brilliant scholar in university library in the Canadian Colony of Norway?”

“No.”

“There you have it. It’s the same thing. It seems we’ve been given flashes of insight throughout this collective dream only to have the same insights snatched away when the entities running the show see fit.” She looked at Evan and turned away. “I have a theory that the memories we made earlier in the dream—the ones we can’t remember anymore—are still in our subconscious somewhere. They’re just inaccessible at the moment.”

“Well, then they’re useless.”

“Not necessarily. Perhaps those forgotten memories will return to us later when we need them. . . Or maybe they will resurface under hypnosis.”

“Oh my God. Are you suggesting we go under hypnosis in the dream?!”

“No, when we wake up, these memories and experiences that we’re collecting now could theoretically be retrieved. But I find your idea of undergoing hypnosis in the dream somewhat intriguing. I wonder if it would work?”

“I don’t care at this point.”

Niyati rested her hand on his shoulder. He didn’t pull away. “Evan, look at me.” He half looked. “This dream that you are the architect of is now as new to me as it is to you.”

The train crossed a bridge over a deep gulch. Evan saw the gulch outside the window swooping up in front of him, turning counterclockwise along the axis of the wooden bridge. He turned around and looked out the windows on the other side of the car where the vault of the sky was sinking under the tracks. No sooner had the gulch become sky and the sky gulch, than the train plunged into a mountain tunnel. Wisps of steam buffeted the glass as the roar of the locomotive echoed in the darkness. The train barreled out of the tunnel and the whistle sounded again and again as they progressed through a misty jungle in the northern Indian state of Rajasthan. The postman leaned out of the train with a hook and seized a bundle of mail dangling from a pole near a telegraph office. A signpost pointed the way to Jaipur.

“We’re slowing down,” Niyati said. “I think the station is coming up.”

Because Evan and Niyati were in a dream, the transition between the train’s stopping and their standing on the platform next to their luggage happened in a matter of seconds. What’s more, the platform they stood on was opposite the side the passengers were detraining from. But they could hear the distant voices of the people making their way into the Art Nouveau station. Before them stretched a tangle of Ashoka trees. The whirring of winged insects and the guttural calls of unidentifiable amphibians lent an air of excitement and mystery to the wild landscape before them.

Evan walked around the pyramid of trunks and suitcases. “Why did you bring so much crap?” he asked.

“I didn’t bring anything with me.”

A woman’s voice called out from the trees. “Open the box on top, Dr Evan.”

Evan squinted his eyes. The librarian from the Canadian Colony of Norway stepped into the light. She wore the dress of an aristocratic adventuress from a late 19th century serial novel. The moment she addressed him as “doctor,” Evan touched his ears and the bridge of his nose to make sure he wasn’t wearing those dorky glasses from earlier in the dream. To his relief he wasn’t.

“Why are you here?” he asked.

“Do as I say!” she replied urgently.

Niyati looked at Evan and spread her arms. He went to the pile and opened the box on the top. Inside lay an ancient khadi scroll the color of beef broth. He removed it and unrolled the delicate cloth. Niyati and he puzzled over the Cheriyal painting with its vibrant colors. Hindu gods crowded the edges of the scroll and a stylized jungle was in the middle. A stark blue line ran through a series of hazards with Sanskrit writing underneath these. The line ended with an X.

“Where does the map lead to?” Evan asked.

“X marks the spot,” the librarian said, “where the map you’re holding can be found.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” he asked, looking at Niyati who seemed as perplexed as he.

“It means, Dr Evan, that in order to find your heart, you must first find the way to it.”

“So it’s like an adventure,” Evan said. It had been a long time—centuries, actually—since he’d felt excited about the dream. His hand went to his holster, but the holster was empty. He didn’t even have a bowie knife or bullwhip. “Goddamnit,” he mumbled.

“Evan!” Niyati exclaimed. She pointed to the train.

Manat was still aboard, dressed in a child’s pinafore with a white bonnet. Her taloned fingers tapped on the window she floated behind.

“Come!” the librarian said, stepping forward and touching Evan’s sleeve. “Manat can do us no harm so long as we remain in the jungle.”

“How so?” Niyati asked.

The librarian gestured to the dark interior of the jungle where thousands of unborn universes floated among the vines and foliage. Manat sank beneath the windowsill. Her talons dug deep into the glass.

“Who’s going to carry our luggage?” Evan asked.

“You don’t need the luggage,” the librarian quipped. “All you need is the map. The luggage on the platform was ejected by your psyches. It’s the emotional baggage both of you have collected since the catastrophe at the Festival.”

“We never made it to the Festival,” Niyati remarked.

“Forget I said that,” the librarian said. She seemed flustered, as if she’d said something she wasn’t supposed to. “Right, let’s go.” She wheeled around and disappeared behind the leaves.

Evan ran after her. “Hey! What’s the point of the map if you already know where we’re going?”

“I don’t know where we’re going,” the librarian said, stopping and sitting on a stone. “I’m waiting for you to guide us.”

“Well, I don’t know where we’re going,” Evan said. “I can’t read this thing.” He held the scroll sideways. Then he shook it up and down like an Etch-A-Sketch, thinking that, since he was in a dream, that might make the words turn into English. But it didn’t work. He groaned. “I wonder why I can’t read Sanskrit anymore. I was fluent in it when I was in the Canadian Colony of Norway.”

“It’s because you no longer have the glasses that so annoyed you,” the librarian noted.

“Maybe I can help,” Niyati said, catching up to them. “I don’t know Sanskrit per se, but I’m fluent in Hindi.”

Evan handed her the scroll. Niyati exhaled and translated the writing under an image that looked like a tree: “Hmm. . . I think it says: Follow the route to the magic mirror in the banyan tree. . . Then enter into—or maybe ‘under’?—the mirror’s reflection.”

Evan nodded. “Yeah, that’s pretty straight forward. We’ve been jumping into magic mirrors ever since this dream began.”

The inert singularities drew close around them, forming a protective cloud as the party advanced over the uncertain ground.

“I’ve been thinking about something,” Evan said, mostly to break the silence which was starting to grate on his nerves. “Are the magic mirrors in this dream portals into unborn universes?”

The librarian shrugged and walked on.

“They must be,” Niyati said.

“Then why don’t inert singularities, like the ones protecting us now, look like mirrors?”

“Evan, I don’t know,” Niyati said dismissively. She saw him roll his eyes. Respect is a two-way street, she thought. “Maybe they are mirrors—but at the subatomic level. Perhaps inert singularities are coin-shaped, and sort of spin around with only one side opening up as a gateway. We just don’t have the instruments to observe them at such a small scale.”

Evan seemed not to have heard. He glanced at the map and looked up. “We need to go left.”

They descended a slope. He resumed the conversation. “Well, I don’t think the magic mirrors in this dream are unborn universes.”

“If you’re suggesting they’re not the same due to the perceived differences in their size, those differences are illusory and relative—especially considering we’re in a dream.”

“No, I wasn’t thinking about their size. I was thinking about the fact that Manat is scared of unborn universes but apparently not scared of magic mirrors. She’s been using mirrors throughout the dream.”

“You’re right!” Niyati said, stopping dead in her tracks. “The mirrors can’t be unborn universes.”

“Yeah,” Evan said. “So the mirrors must lead to places that already exist.”

“That would mean the mirrors we encountered in the hedge maze in Hell—”

“And in the Tent of Magic Mirrors—”

“All of them!” she exclaimed. “They must be gateways to places that already exist!”

The librarian (who didn’t exist) was finding their conversation irritating. But something in the distance caught her eye. She extended an antique spyglass that materialized instantly in her hands and peered through it. “The banyan grove is down there,” she said, pointing to the hollow of the valley.

The three made their descent. The inert singularities floated ahead to light the way. Evan folded up the map, put it inside his cowboy hat, and put the hat back on.

An eagle-owl hooted as they entered the banyan grove. It didn’t take long to find the magic mirror. It stood upright against a banyan tree in a shallow puddle of water. The mirror reflected what looked like a pond in the hazy light of a balmy afternoon.

“There it is!” Evan remarked.

Niyati gasped.

“What?”

A second mirror stood on the opposite side of the grove between two crumbling Hindu ceremonial pillars. The face of Manat contemplated them from the mirror, but the face was no longer that of a child. It was a pale and grotesque face with glowing red eyes.

The librarian whispered: “Remember, Manat can do us no harm so long as the singularities remain with us.”

Evan looked at Niyati. “In the hedge maze all we had to do was wish ourselves into the mirrors.” They closed their eyes and wished themselves into the pond on the other side of the glass. But nothing happened.

“We must be doing something wrong,” Niyati said.

The demoness parted her lips, exposing three rows of fangs. She emitted a deep vibratory tone that caused the glass of the mirror in the banyan tree to quiver. Three cracks formed in it.

Evan touched the mirror, wondering if they were supposed to step through it, instead of merely wishing themselves into it. He was afraid to apply too much pressure to the glass since the cracks might spread or the mirror shatter altogether.

“Quick!” the librarian said. “What did the inscription on the map say?!”

Because she had 98 percent recall, Niyati repeated verbatim what she had said. “Follow the route to the magic mirror in the banyan tree. . . Then enter into—or maybe ‘under’?—the mirror’s reflection.” Her eyes expanded. “Evan!—Remember the story of Mama Margot Ashwiyaa?”

“Yes!” he replied. “I wondered why I had experienced her story as if I’d lived it myself!”

“She didn’t enter the Lodge House on the island in the Lake of Galilee.” Niyati pointed to the puddle at their feet. “She entered the reflection of it!”

“So we’ve got to enter the mirror’s reflection by entering the reflection of the mirror in the puddle?!”

“Yes!”

Evan beckoned to the librarian. “Come on!” Then he and Niyati joined hands and sprang into the puddle. They landed in the pond on the other side of the mirror in the banyan tree.

The librarian jumped in after them. Manat howled and the mirror shattered as the inert singularities condensed into a funnel that tried to sink into the reflection as well. But only fifty made it through.

The adventurers stood waist deep in the pond.

“We did it!” Evan said, embracing Niyati.

“Yes,” the librarian added. “But we suffered losses.”

The fifty singularities that remained circled the three protectively.

Though he had lost his heart, Evan was starting to trust Niyati again. And with trust, his affection for her was rekindling. “We make a great team,” he said. “You’re super smart and sometimes I have good ideas too.”

“What about me?” the librarian said. “If it hadn’t been for me, you wouldn’t have remembered what the map said.”

“You don’t count,” Evan said. “You don’t exist.”

The librarian seemed crestfallen. The fifty singularities grew dim.

“Evan,” Niyati said. “Why would you say that?”

“But it’s true,” he said.

Niyati glanced at the librarian apologetically.

“It’s alright,” the archetype said, her eyes brimming with tears.

Evan didn’t apologize, but the librarian’s tears bothered him. He turned away as he spoke. “We have to keep going. I see a light beyond the trees—that way.”

They made slow progress through the pond. Some of the singularities dove under the water to ensure nothing harmful lurked beneath.

When they had made it to the shore, there was a deep rumble and the ground shook.

“Stay here,” Evan said. “I’ll check it out.” He sprang over the vines, crept behind the trees and looked out at the clearing. A line of elephants was advancing in his direction. He stepped in their path. All of a sudden the leader trumpeted in joy and broke away in a trot.

“Evan!” it cried out.

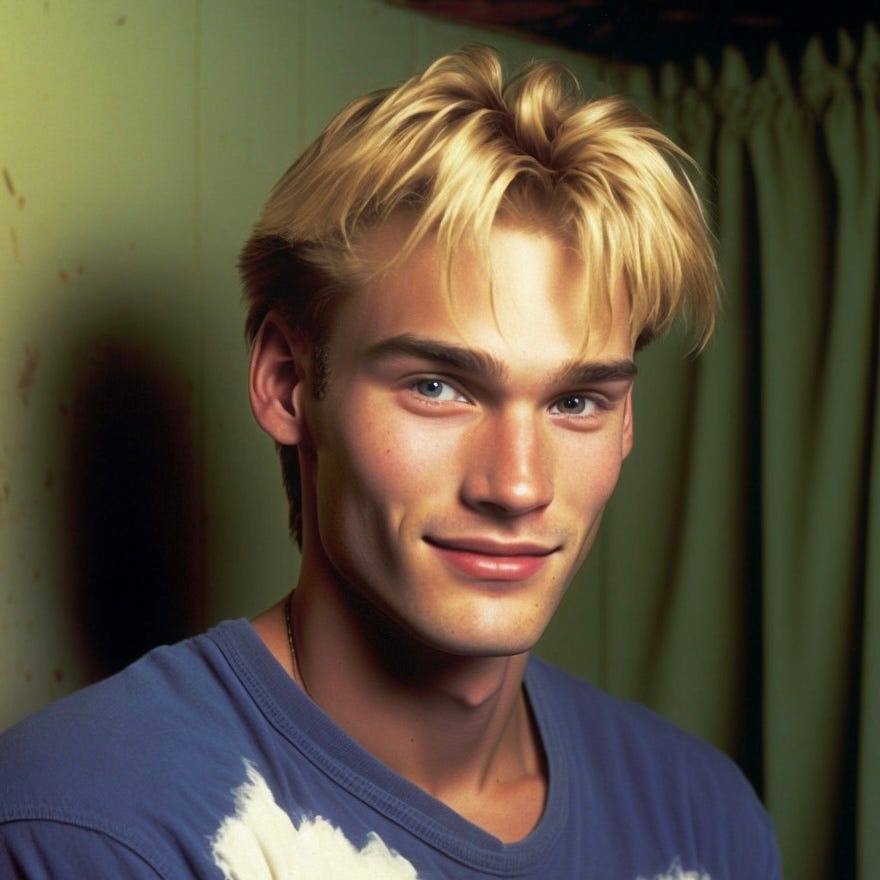

“Levi?!”

“I’ve missed you sooooo much!” the elephant said. Levi’s proboscis coiled around Evan’s body.

“I’ve missed you too!—Dude, watch it! Jesus!”

“Sorry!” Levi said as his trunk slipped out from between Evan’s legs. “I’m still learning to control it.”

Evan shouted over his shoulder, “It’s alright! You can come out!”

Within no time Niyati and the librarian had emerged from the jungle and joined them.

The other elephants stood motionless. Levi was their leader. They had no independent existence in the dream without him.

“I’m not a good leader like you,” Levi lamented. “But I’m getting used to it. I don’t like having to tell others what to do. It feels kinda bossy.”

“Being a leader is all I’ve ever really known,” Evan said, removing the map from his hat. “I’m pretty Alpha like that. I’m prolly gonna be a wrestling coach someday. . . Anyway, we’re on a quest. We’re following this map to the original version of it. Because that map leads to my heart.”

“That makes perfect sense to me,” Levi said. “Hold the map up in front of one of my eyes so I can see it.”

Evan unfurled the scroll and did as Levi had asked.

“Got it!”

“Are you sure?” Niyati asked, stroking Levi’s ear. “The print is small and the map’s a bit faded.”

“It’s in my noggin now. An elephant never forgets! The place you’re going to is pretty far away. If you guys want, you can climb up onto my back and I can take you as far as the rope bridge.”

“That sounds great!” Evan said.

Levi lowered himself to the ground so that Evan and Niyati could climb up into the canopied seat that had miraculously formed on Levi’s back. The seat was cushioned with soft bolsters.

The librarian said that she would ride in the back to keep a lookout for any danger from the rear. But this was unnecessary since the unborn universes were already keeping watch. Truth be told, the librarian was still hurt by Evan’s remark that she didn’t count “because you don’t exist.” That really hurt. She wanted to be left alone so she could brood on it.

Over the course of what seemed like a single day, Evan and Niyati traversed millions of miles through the Deccan peninsula. The lovers lay in each other’s arms and were lulled to sleep by a symphonic rendering of Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day” that somehow echoed in those empty chambers at the back of their minds, which had formerly been occupied by the emotional baggage they left on the platform in Rajasthan. Both dreamed they were looking down on their sleeping astral forms, and from this above-hovering position each witnessed the other momentarily wake, brush a lock of hair from the beloved’s closed eyes (a caress the floating observer felt), and then fall back asleep, as the phantom form sank back into the navel of the slumbering astral form that had projected it up and over them in the first place.

But what the unconscious minds of Evan and Niyati were unaware of at the time was that the perceived “single day” was in fact a protracted (and retracted) event that two powder-blue aliens on the desert planet of Satcitananda were tracing in the sand. One of the aliens was an embodiment of the Absolute Past; while the other was the embodiment of the Absolute Future—and the two had fallen in love. They drew their fingers through the time-bearing sands, forming spirals and arcs. And each grain they disturbed represented 10,000 years. Thus, Evan and Niyati were dragged billions of years into the past only to be catapulted billions of years into the future. But when the individual grains of sand were tallied, it was discovered that the respective quantities differed by a single grain preponderating toward the future, which meant that the lovers on the desert planet of Satcitananda, as well as the lovers snuggled up together on Levi’s back, experienced a single day that lasted 10,000 years. And both pairs of lovers assessed this single day to be about as perfect as the one Lou Reed was singing about in those now vacant and unencumbered chambers at the back of their collectively unconscious mind.

At break of day, Levi trumpeted that the sun was rising in the west. They had arrived at a rope bridge spanning a dark ravine.

“End of the line,” Levi said in a sad and wistful voice.

The three adventurers dismounted. Niyati and the librarian stepped away so the two friends could bid each other farewell.

“Thanks, buddy.” Evan said. “I’m not sure when we’ll see each other again.”

“I’m not sure either,” Levi replied, as he walked away. “But I can assure you that I’ll be there for you when you need me the most.”

Evan felt a sudden and inexplicable sense of regret. He had heard those words before—somewhere else in the dream. Perhaps in Hell. He couldn’t recall. He brushed a tear from his eyes as the last of the elephants disappeared into the jungle. Then he went to the bridge.

Niyati and the librarian stood waiting for him.

Evan confronted the librarian. “You aren’t real. So you don’t have a heart. But I saw you weep.”

“What of it?” she replied.

“How can something without a heart weep?”

Niyati didn’t like where this was going. In an effort to de-escalate the situation before it got out of hand, she intervened. “Some of the most heartless tyrants in history were easily moved to tears.—Oh, and crocodiles weep to lubricate the nictitating membrane of their eyes.”

Evan turned away from them and stared dumbly at the footprints in the path where the elephants had stood.

The librarian sighed before replying. “There’s a difference between a physical heart and a metaphorical one, Dr Evan. Your physical heart is still beating in your sleeping chest aboard an airplane transiting the Pacific Ocean. Otherwise, you’d be dead.” She paused. She needed to tread carefully, because she was forbidden from telling Evan he had already died once in the dream. “However, your metaphorical or spiritual heart—whatever you want to call it—has been seized by the demoness Manat.”

When she said “spiritual heart” Evan saw again that strange and somehow vivid memory he had of Mama Margot Ashwiyaa entering the reflection of the lodge house in the Lake of Galilee, where the Havasupai man opened his chest and revealed to her the Sacred Heart.

“You didn’t answer my question,” Evan persisted. “How is it that you and I can weep if neither of us has a heart?—Metaphorical, spiritual, or otherwise?”

“As you said, Dr Evan,” the librarian smirked, “I’m in the same boat as you. So I can’t answer that question, can I?”

Evan’s shoulders slumped. He studied his boots.

The librarian softened her tone. “I can’t answer your question. But I can reframe it as a statement.” He looked up and saw that her eyes were wet. “You don’t need a heart to weep,” she said. “You need a heart to understand why you wept.”

Nice close, Daniel: “You don’t need a heart to weep,” she said. “You need a heart to understand why you wept.” 🔥