If you’re joining us just now, follow the snake’s tail to the Prologue or climb a ladder to the Table of Contents.

Chapter 7: Shiva’s Dance of Destruction

A blue-white fog rolled off the stage that stood between the card catalogs of the dim-lit reading room in the university library in the Canadian Colony of Norway. The stage was deserted because the band was taking a break. But there was literally nothing on the stage other than the fog: no instruments, no chairs, no sheet-music stands, no microphone. These items would come back into non-existence when needed.

Levi approached the broad oak table that Evan and Niyati were sitting at. He looked left and right to make sure the librarian was nowhere in sight.

“Woooooo,” he said, like an adolescent trying to sound like a ghost.

“No way!” Evan blurted out. “That was you tugging at the book chain upstairs?!”

Levi nodded and grinned. He wore a black turtleneck and took a seat next to Evan.

The two friends laughed (and the canned laughter laughed with them), because they now had all the ingredients for a knee-slapping Freudian joke about a gay guy yanking a straight guy’s chain and the straight guy kind of enjoying it.

“I like your glasses,” Levi said.

“Really? I hate ‘em. I think they make me look dorky.”

“No, bro!” Levi said, producing a shaving mirror and holding it so that Evan could see his reflection. “Take a look.”

Evan looked skeptically into the mirror and shrugged: “I guess they’re okay.”

“Trust me,” Levi said. “You look really good.”

Niyati drummed her fingers on the table and smirked enigmatically.

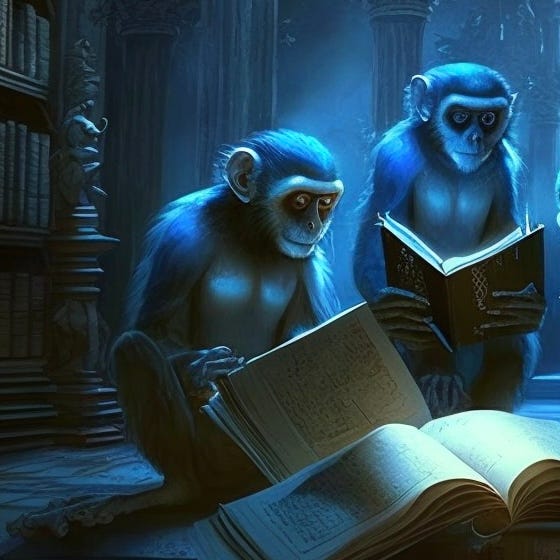

Scores of macaques, chimpanzees, orangutans, and baboons began entering the reading room. They were very well behaved. They couldn’t talk to the humans, because they weren’t in a children’s story.

The chimpanzees were there to conduct research: they’d been tasked with typing out “all of Shakespeare” on an old-timey typewriter (a rather broad and vague mandate), and they weren’t sure which edition of the Bard’s works they were supposed to use as reference. Plus, there was some confusion about which orthographical system was the most appropriate for consistency’s sake.

The macaques were desultory readers. They had little patience for non-fiction and tended to lose interest in novels after the sixth chapter: they tried reading the very novel they were in, but never made it to this paragraph. Their poor reading habits did not deter them from checking out scores of books at any one time and schlepping these home in canvas bags. But they tended to forget they checked the books out until the overdue notices came rolling in.

As for the orangutans, they would read books if they had to but preferred watching sitcoms because they hated to think. The baboons neither read nor watched TV, because they were wild animals. But the surly leader of the baboons was curious about the humans. He went to the table and looked narrowly at the wooden chairs that Evan, Levi and Niyati were sitting on. He implied by his facial expressions that the chairs did not seem comfortable; and then he bared his red ass and walked away in scorn.

The librarian rushed to the table, because the baboon’s behavior had reminded her of something. She addressed Evan in unaccented English, which she could now speak with complete and utter fluency. And this was because she had been thinking things over as Evan was reading the iron-bound history of Snakes and Ladders. And as she wandered from gothic corridor to gothic corridor in the ancient university library in the Canadian Colony of Norway, she felt herself overcome by a sudden and overweening passion for the inert singularity, whom she loved.

Often she would stagger in a swoon over the storm-blasted cliffs of the German Romanticism collection, shelving the poetry of Goethe and Kleist as the lashing rain beat against her tear-moistened cheeks. She clutched her withered breasts and wondered aloud if she was too old for him, too provincial. She stole furtive glances at the singularity from the library’s alcoves; and, turning away in mute despondency, tore her hair in inarticulate despair.

She tried to lose herself in her work; and from her desk by the front door, she stamped the due dates iron-fistedly at the backs of the books before handing them to the flabbergasted chimpanzees. When the last of the patrons had filed out of the building for the day, she would turn over the sign on the door to signify that the library was officially stengt. With quill and ink, she drafted stern notifications to the delinquent macaques, who had never known her to be so curt and acidulous in her correspondence with them before.

But then, one magical day, it happened: a sudden inspiration, a revelation that came to her ut av det blå (“out of the blue”). It was an idea that uncorked all the vials of her hope—an idea that upwardly perked the corners of her lips into an unctuous smile. She rose from her desk, and tilted her head in hesitating inquiry. Then she calmly asked her colleague, Madame Blavatsky, if she could perhaps monitor the front desk for a few minutes “because I need to powder my nose.”—Gentle reader, this was the most deceptive thing that the librarian had ever said in the course of her non-existence! But she felt that she must lie to Madame Blavatsky, because she was not confident that her plan would succeed; and were it to fail, she would be exposed to the unbearable calumny and ridicule of the entire population of the Canadian Colony of Norway, every man jack of whom lived outside the library’s walls.

The idea that had come to her was this: If she were to learn English, then the singularity might be impressed with her and see her as a real woman, instead of just an archetype in other people’s dreams. He might invite her to the conservatory, seize her by her wrists (despite her expostulations), loosen her bodice laces, call her his little puss, and then maybe. . . just maybe.

And so in lieu of going to the loo, the librarian slipped into the narrow confines of the inutility closet, which had never been used before because it was entirely useless. It was the largest and most opulently decorated room in the university library in the Canadian Colony of Norway. The mouldering treatises on the shelves were devoted entirely to vain and useless things: haute couture, cosmetics, hair dyes, motivational speakers.

A dusty full-length mirror mounted on the wall reflected the guttering flames of the candelabra on the marble table. Wavering gouts of sickly light danced between the cracks in the glass. The librarian lifted the candelabra. There was a click and the mirror swung inward.

With the candelabra in hand, the librarian descended the rotting staircase into the gloomy dungeon. Heavy chains that had no purpose other than to sway and dangle ominously overhead had been installed in the dungeon at the behest of the Venetian architect Giovanni Piranesi.

Two folding doors of bronze loomed before the librarian. She pulled a hidden lever, and the groaning hinges echoed in the dank and clammy air, as the doors swung open and disclosed a nighted expanse. A mephitic vapor issued from the cobwebbed interior of the English language collection.

From a warped bookcase near the door, our heroine withdrew a slender volume: it was the very thing she sought, an English primer written in the latter half of the 18th century by the rector of the University of Uppsala. And so, overcoming her hatred of the Swedes, which was rivaled only by her hatred of the Canadian oppressors, the librarian opened the book and studied the quaint and tasteful woodcuts that adorned its pages. She read aloud (at first hesitatingly, but then with mounting confidence) the first two sentences that her eyes lighted upon: “Whither, perpend, has Mary’s pussy gone?” and “See Thomas fondle his resplendently crested cock.”

—But the librarian set these ruminations aside, because there was something she urgently needed to divulge to Evan: “A piece of the puzzle,” she said, “for this scavenger hunt you’re on.” Evan told her that what she had just said was a mixed metaphor. The librarian apologized and explained that she was still learning English. Then she said, “Are you ready?” And Evan hoped that she wasn’t contemplating a lewd move, but he said that he was.

Then she hiked up her velvet dress and showed her red baboon’s butt. She said that she had been a primate all along and that Evan needed to remember this, because its implications were profound.

She shrieked like a thing unholy and unfeminine; and sprinted up the spiral staircase to the second floor. She clambered up a bookshelf in utter disregard of the rare volumes that tumbled to the ground in her wake. (It was a blatant violation of the sacred oath she had taken to preserve and safeguard all books, even dirty ones, since, just as the Grace and Majesty of God are often found in the cesspits and cloacae maximae of the world, so too does the Word of God run like a golden thread through obscure, long-neglected, and often unseemly works of literature.)

When she had reached the top of the topmost bookshelf, the librarian leapt up to the painted ceiling and seized the lower rung of a ladder that led up to the Devil’s red ass. But just before vanishing into the Evil One’s anus, she couldn’t help but to throw out a parting remark, filled with all the force and acrimony of the Prophet Jeremiah: “It is a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done. It is a far, far better rest that I go to.”—And she said these things because she had always been intentionally Dickensian. And as she looked one last time at the fucked-up face of the Angel Gabriel, she shed a bitter tear and said (more to herself than to the assembled primates below), that at last she would find peace and be free from the wily machinations of the Canadian oppressors. But what no one realized at the time was that the librarian was merely exiting the scene for a costume change.

Levi said, “I have to go help Gordon get ready for his act. He’s up next.—I’m in the act too, and it’s making me nervous. I’ve never been onstage before.”

“Tell Gordon I told him to break a leg,” Evan said. “Actually, don’t tell him that. We’re in a dream and it might come true.”

“Don’t be nervous, Levi” Niyati said. “You’re playing the game well.”

“Thank you!” he said. And then he ran up the steps and vanished in the blue-white mist on the stage.

The emcee of the Astral Plane suddenly appeared at the microphone, which was one of those clunky 1940s affairs. He adjusted the stand, tapped on the mouthpiece and said “is this thing on?”—and a burst of acoustic feedback caused Evan to spill the highball he was raising to his lips.

The emcee’s way of speaking, which Niyati found intriguing, was rather complicated and riddling. Although he seemed to be addressing the room, he could only speak to one entity at a time; yet he never turned his gray eyes to the entity he was speaking to. Furthermore, he could not talk directly to any of the archetypes; he could only talk about them. The only entities on the Astral Plane whom the emcee could address were the souls of dreamers from the planet Earth (where the sun sets in the east). Thus, when the emcee said “is this thing on,” Niyati realized that he had been asking her if Evan was paying attention, even though he had been looking directly at Evan when he said this.

And now he smiled at the audience, and then turned his face again to Evan, because he needed to say something to Niyati: “You should probably stop thinking about the way I talk,” he said, “and start thinking about the what instead.”

“What?” Evan asked.

“Precisely,” the emcee said, as he answered Evan by looking directly at Niyati.

There was a drumroll followed by a cymbal crash.

The emcee raised his white-gloved hands: “Our last number is actually our first,” he remarked. Then his gray eyes looked up at the library’s painted ceiling with its promiscuous depiction of the Last Judgement and the Fall of Man. It was clear that the painting was related to what the emcee was about to say. But Niyati was confused, because she knew he could only address one dreaming entity at a time—even though his voice could be heard by all. But she couldn’t figure out whether he was talking to her or to Evan. It wouldn’t make sense that he was addressing Gordon or Levi, since they were both backstage and were therefore not participants in this part of the dream. Yet no other dreamer in the room from the planet Earth (where the sun rises in the west) was present, at least as far as Niyati could tell.

Madame Blavatsky grinned slyly as she rose from her desk near the library’s front door.

The emcee continued to speak without removing his eyes from the ceiling: “We’ve been rehearsing this number for most of our non-existence. . . In fact, Blind Rufus over there can vouch for me when I tell you that this number is like nothin’ you ever heard before, at least this side of Judgement Day.”—And Blind Rufus, who was the meekest and gentlest archetype on the Astral Plane; and who played the bass like an angel (assuming angels play basses), nodded and told his bandmates on either side of him, “It’s true, it’s true.”

Since the emcee could not address Blind Rufus directly, he was unsure whether the archetype had heard what he’d just said about him. But the show must go on, the emcee thought. So he said, “Put your hands together, ladies”—(looking at Evan)—“and gentlemen,”—(turning to Niyati)—“as we present to you our rendition of Shiva’s Dance of Destruction.”

The drummer clicked his drumsticks thrice and said “1, 2, 3”—and a bluesy saxophone blared out a tawdry air that sounded like something out of a New Jersey strip joint. The footlights came up and Gordon took to the stage. Levi quietly stepped behind Gordon, since he would be pantomiming Lord Shiva’s other two arms.

The macaques, chimpanzees, orangutans, and baboons were now talking volubly and jovially because they were finally in a children’s story.

Gordon did a saucy move: he bent his knees and put one index finger to his lips and the other on one hip, as he made a sizzling sound and Levi executed jazz hands from behind.

An orangutan went to the stage and slipped a buck in Gordon’s longyi and said, “Great job, man!” Gordon thanked him. The orangutan responded with an opposable thumbs up as he returned to his seat.

But there was a heckler in the room, a plastered macaque who shouted at the top of his lungs that Gordon was the fattest Shiva he’d ever seen.—And Blind Rufus, who didn’t care for mean-spirited name-callers, whispered to the saxophonist, “Who is that cat?” And the saxophonist said he’d never seen him before. Everyone was wondering if Gordon was gonna take offense and shut the heckler down. But Gordon took it all in stride.

He kept gyrating lasciviously as he thought about how he should respond. Then he came up with a calm come back (that was neither snippy nor snappy) and he said, “The Puranas don’t specify that Shiva’s a skinny dude. Besides, I’m actually Lord Krishna, which means I’m everything and everyone in the universe—including all y’all.”—Then Gordon’s head transformed into the elephant head of Ganesha (god of good luck). “How’s this mask?” he asked. “Goes with the blubber, right?”—and the canned laughter laughed.

“Haven’t you had enough?” Niyati asked Evan, pointing to the three empty shot glasses in front of him.

“I don’t even remember drinking them,” he replied.

Gordon overheard. “Pace yourself, pal,” he said. “Nothin’ wrong with a pick-me-up every now and then. But listen to your friends when they’re tryin’ to help. I could give you an earful about the pitfalls of demon drink.”

Evan didn’t appreciate Gordon’s unsolicited advice. So he looked back down at the iron-bound book in front of him. It was still open to Chapter 1. He noticed a dot in the upper right-hand corner of the page. The next page had one too. So he started rifling through the pages and—ta-da!—and this created a moving picture: a cartoon of an inert singularity that expanded and jiggled like a living raisin, and then a second raisin appeared out of nowhere and the two danced together, and held their hands until they collided and—boom!—out came “Shiva Nataraja” doing a dance that mirrored the dance Gordon was doing onstage.

One of the chimpanzees, a scholar of Jacobean theater who’d written a monograph on Marlowe’s influence on Shakespeare’s Henry VI Parts I, II, and III, addressed Gordon respectfully: “Pardon me, but may I enquire, are you going to act in this performance? Or is it just an interpretive dance?” It sounded like the chimpanzee was trying to be a smart ass, and many of the spectators in the audience gasped, groaned, or said “good grief.”

But Levi sensed the chimpanzee was just a socially awkward primate, and that was something Levi knew a great deal about. So he whispered in Gordon’s ear and said, “The chimp didn’t mean to sound like a booger. He’s just genuinely curious.”

Gordon nodded casually because he’d suspected the same. “I hadn’t thought of acting while dancing,” he said. “Whaddya have in mind?”

The chimpanzee became flustered. “Oh!. . . I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to offend.”

Gordon and Levi raised their arms simultaneously and formed a double “V”.

“No offense taken, George,” Gordon said. Then he smiled kindly at his fellow primate; and the chimpanzee smiled back.

Then Gordon raised his eyebrows, “How about I recite a few lines from the Bhagavad Gita?”

Madame Blavatsky glided slowly toward the table Evan was sitting at. No matter where Evan was in his dream, Madame Blavatsky was somehow always outside of his field of vision; just like the inert singularity. Furthermore, she had started out at the front desk near the entrance to the library, which Evan had been facing ever since he had fallen from the ceiling above. Yet he still he had not noticed her.

The astral form of Madame Blavatsky was expanding like a balloon, as she approached Evan from behind. But Niyati saw her coming.

“Evan!” Niyati shouted. “We have to go! Run!” Evan followed her as she made her way through the audience, and pulled him toward the stage.

Gordon’s face had undergone a transformation and was now the black-and-white face of J. Robert Oppenheimer. “I am become Death,” he said. “The destroyer of worlds.”

Levi backed away from Gordon and went to the scrim on rollers against the wall. He moved it aside, so as not to reveal the trick. And Gordon looked over his shoulder to make sure Levi wasn’t screwing things up and giving the goods away.

Behind the scrim was a black curtain weighted at its base. Levi lifted the curtain and waved Niyati and Evan through. When the curtain fell, the wall turned to stone.

Clenching her black-gloved fists, Madame Blavatsky emitted a soundless scream as she floated upwards and backwards, head over heels, into the blue-white mist that suffused the university library in the Canadian Colony of Norway. When she reached the painted ceiling, her astral form condensed and then slowly disappeared into the closing mouth of the angry Jehovah.

"...the shelves were devoted entirely to vain and useless things: haute couture, cosmetics, hair dyes, motivational speakers." That tickled me mightily :-D

Who hasn’t been heckled by a plastered macaque? Occupational hazard.