If you’re joining us just now, follow the snake’s tail to the Prologue or climb a ladder to the Table of Contents.

Chapter 1: The Playing Pieces

Evan rode the escalator up to the second floor of the airport. The step he stood on flattened and slipped under the steel panel as he reached the top. A woman’s voice told him in an Australian accent to “mind” his step instead of “watching” it. The recording was on a loop and Evan thought to himself: “mind” your step. It gave him an idea for another metaphor for life—something about looking where you’re going with your mind instead of your eyes. But this revelation would need a bit of licking into shape. He couldn’t wait to share these insights with his crew when he got back to UCLA. He’d have them over on Friday night. Marcus would bring the bong.

“Dude…” Evan would say (and he’d say “dude” in the singular even though he was addressing six dudes), “I think—like, when you travel to different countries, you know? And you spend time experiencing nature and visiting sites that are far away, it opens up all these windows in your mind, and you see things, like, how they really are. Like, I dunno, like you see ahead and behind, but ‘behind’ as in time… like the past, which becomes the future while you’re looking at it.—It’s hard to explain.” Then he’d cover the bong’s kick-hole and take another hit.

Evan stuck his right hand in pocket to make sure the unborn universe was still there. He hoped it didn’t slip out during the flight. (They were sneaky and elusive like that.) He must’ve picked it up when he was on the beach in Sydney. He was glad the sleepy-eyed yawning X-ray dudes let him keep it, because now he had a keepsake to remember that trippy experience on New Year’s Eve.

It had been late afternoon in Sidney. After a short nap in his hotel room, he did fifty pushups, put on his pink Bermudas and headed down to the lobby for his last touristy excursion before the year ended. A hotel shuttle was heading out to Coogee Beach. The shuttle would return forty-five minutes later. Evan had used the same shuttle service two days prior to visit Shark Bay. But Shark Bay was rocky and overrun with tourists, so he’d gone back to the shuttle and slept until the others returned because he was hungover.

But Coogee Beach—wow!—that was different. There weren’t a lot of people there because everyone was getting ready for the night’s festivities. Evan told the shuttle driver not to wait for him, because he would probably stay for a couple hours. He’d get a cab back.

The late-afternoon sun was sinking in the east. Evan removed his sneakers and socks and left them on the sand. He went wading in the surf but didn’t let the water get too far up his legs because he didn’t want to get his pockets wet. His wallet and passport were in them.

He closed his eyes for a solid minute and faced the breeze. Then he looked down and admired the shifting contours of the dark wet sand at the water’s edge. The shadow of the receding surf writhed and vanished seaward and the lines formed loops like snakes. The ribbed sand looked like ladders. And he thought of that board game he’d learned to play so long ago. He was suddenly aware of a presence nearby. He looked up.

A South Asian woman stood about 10 feet away. She held her sandals by the straps. She was beautiful. They smiled kindly at each other. When she spoke, she sounded American. She said her name was Niyati. Evan remarked that there used to be a girl named Niyati who lived next door to him in Pasadena.

“Holy shit!” Niyati exclaimed. “Evan?!”

“Yes!” he grabbed his head in disbelief.

She said she hadn’t seen him since they were kids. She too was on vacation and would be heading back to California in a couple of days.

The slanting rays of the setting sun threw a glamor on the surf and the clouds until the rosy hues of twilight matched the blush on Niyati’s face and the color of Evan’s Bermudas. The whole dreamy landscape became as soothing as the sound wind chimes make. And Evan heard the wind chimes hanging from the eves of his backyard on that summer day in 1979.

They were 7 years old when they met. Evan saw her playing next door on the day his family moved in. He had no idea that Niyati’s family (his new neighbors) would be moving to Santa Ana within the week.

Niyati knocked on Evan’s front door on the Saturday morning after they had moved in. She held a decorated teak box in her arms.

“Can the boy who lives here come out and play?” she asked.

“Let me ask,” Evan’s mom said.

She went into the den where Evan was sitting on the floor amid the unpacked boxes watching the boob tube.

“The girl next door is here,” mom said. “She wants to know if you’d like to come outside and play.”

Evan’s favorite Saturday morning cartoons were over. “I guess,” he said.

Niyati’s hair was tied up in two ponytails and she wore pink-framed glasses. She told Evan that she had a game that she’d like to teach him how to play. She rocked the teak box back and forth.

“Okay,” he said.

They went to the backyard and sat on the broad wooden deck.

Evan’s mom asked if they wanted Fantas. Niyati said that would be nice, but Evan asked for a Dr Pepper instead.

He felt a need to show the girl with the glasses how smart he was, so he volunteered to open her Fanta for her. He said, “If you pull the tab off the can and drop it inside—like this—the tab won’t come out, because now it’s all curled up. That way you won’t accidentally throw the tab on the ground and step on it with your bare feet.”

—“I still do that to this day,” Niyati told Evan on Coogee Beach in the final hours of 1993.

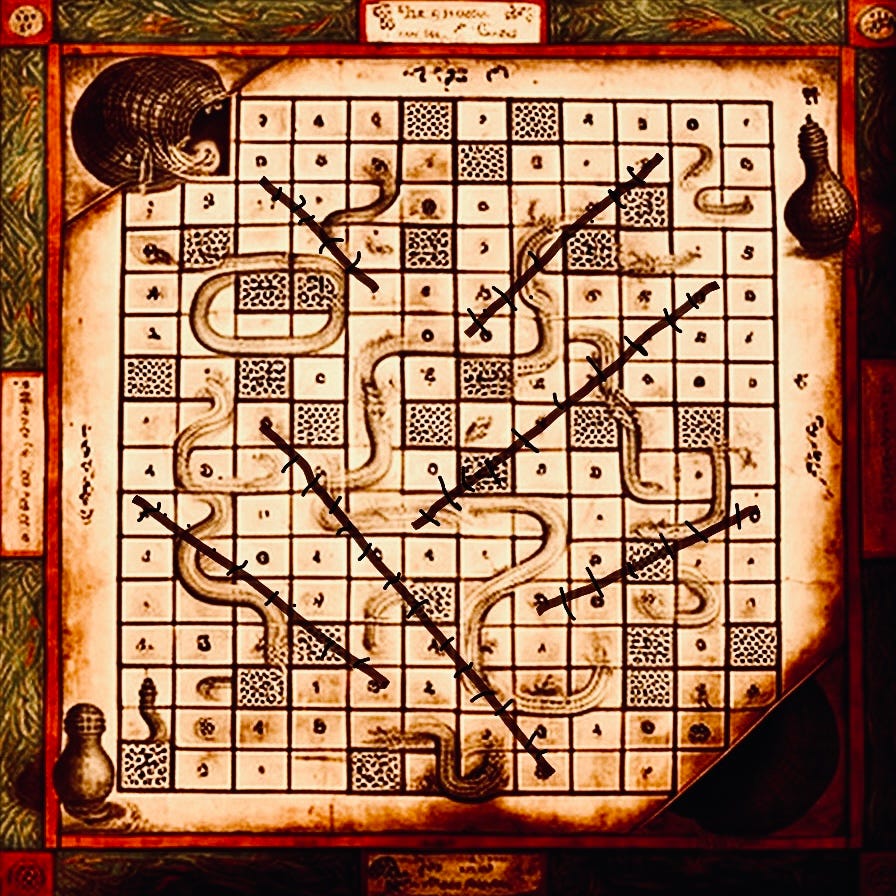

Niyati opened the teak box and unfolded a game board arranged in a 10 x 10 grid. The gameboard was hand-painted, but old and faded. There were burn marks at the edges. The grid was covered with bamboo ladders and spotted snakes.

“It’s called Snakes and Ladders. The game board was made hundreds of years ago by an ancestor of mine. He was holy man who lived in a city called Varanasi in India.” Evan would later learn that Veranasi was a city that didn’t exist on the planet Earth where the sun rises in the west. It was a mythical place, like Avalon or Oz.

The teak game box also contained a worn leather cup for the die and four colored playing pieces with Hindu images carved on them. The pieces represented a priest (white), a warrior-king (red), a merchant-farmer (yellow), and a minister (black).

Evan knew the words “farmer”, “warrior”, “king”, and “priest”, but he didn’t know what a “merchant” was.

“What’s a merchant?” he asked.

“When you go to the store. The person who sells you things is called a merchant.”

“What about people who come to you and sell things? Like the ice-cream man? Is he a merchant?”

“Yes! Very good!”

That’s a smart-aleck way to respond, Evan thought. He looked back down at the pieces.

“What’s that piece called again?” he asked, pointing at the white piece.

“The priest.”

“And that one?”

“The minister,” she said.

“So if there’s already a priest,” he asked, “why is there a minister too?”

“You’re thinking of a Christian minister. There’s another meaning of the word minister. A minister can be a person who gives people advice.”

“Like a priest?”

“Umm,” Niyati said.

Evan grinned. He was glad she wasn’t as smart as she acted.

“I’m just going to call these pieces by their colors,” he said.

“Black and white aren’t colors,” Niyati replied.

If black and white weren’t colors, Evan didn’t know what they were. He decided it wasn’t worth arguing over, so he sipped his Dr Pepper in silence. She apparently liked saying things that didn’t make sense and saying them in a way that made her look like she knew what she was talking about.

“I think you should be the warrior-king,” Niyati said.

“Red,” he replied.

“And I’ll be the priest.”

“White,” he said. Then he thought of something. “Can girls be priests?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” Niyati said and pushed up her glasses. “The word for priest is brahman in Hindi.”

“What’s Hindi?”

“It’s the language my mom and dad speak. I only know a few words. Hindi comes from an older language called Sanskrit.”

Evan finished his Dr Pepper, crushed the can to show how strong he was, and said, “How do you play this?”

Niyati said the rules were easy. “You roll the die and move your piece along these squares—all the way down this row. Then you move in reverse on the row above. The path the pieces follow on the gameboard is called boustrophedon, which is an ancient Greek word that means the path an ox follows as it draws a plow over a field.”

Evan furrowed his brow and looked at her. He’d never heard someone his age talking the way she was talking.

“You have to get to the square here at the top and land on it by an exact roll of the six-sided die. If your piece lands at the bottom of a ladder, you climb to the top of it. If it lands on a snake’s head, you fall down his scaly back and land on the square where the tip of his tail is.”

Though he was only a child, Evan picked up on a flaw in the game.

“So,” he said, “I can’t make choices in this game—to move myself ahead.”

“Correct,” she said. “The game is deterministic.”

He had never heard the word “deterministic” before and assumed it was also Hindi.

Niyati looked at him and touched her chin. “When you say that you can’t make choices in this game, I think what you’re alluding to is something called strategy. This game has no strategy. But it’s still fun, because you can’t predict chance, so it’s always a surprise how the game will proceed.” (He noticed she hadn’t said “how the game will end”.)

Evan rolled the die and moved three spaces. He landed at the bottom of a ladder and got to move up five levels. Niyati rolled a six and remained on the first level. It should’ve been a quick game, but it wasn’t. They played and played for an hour. Then Niyati had an idea.

“Let’s add the other pieces. It’s more fun that way. We’ll roll for them.”

“Alright,” Evan said.

The merchant-farmer and the minister were added. Surprisingly, the two newcomers advanced more rapidly along the game board than the priest or the warrior-king.

“They’re doing better than we are,” Evan said.

Niyati laughed. “They’re not doing better. It’s not a competition. You’re supposed to enjoy the journey.”

“You talk like an adult,” Evan said.

“I’m considered a prodigy,” she replied.

“I don’t know what that means but it sounds right.”

Niyati rolled the die on behalf of the minister, who had made it to the top row. They played another round and, when it was the minister’s turn, Niyati rolled the exact number the piece needed to get to the last square.

Niyati moved the minister to it and said, “Moksha!—That means ‘release.’ Good job, Mr. Minister!”

She put the black chip in the teak box.

“Can we keep playing?” Evan asked eagerly.

“Of course we can keep playing,” Niyati said.

Evan was enjoying himself. He didn’t know why but there was something about this game that was making him happy. Maybe it was this new friend he’d met that made it so fun.

“I want to see if I can get to the last square before you,” he said.

He rolled the die and moved two spaces. Niyati moved four. Evan rolled for the merchant-farmer and the piece advanced three spaces and landed on a ladder that carried it to the top row. When the merchant-farmer’s turn came again, the piece landed on the last square.

“Moksha!” Niyati said.

“Moksha!” Evan repeated. He put the merchant-farmer’s piece in the box. Then he looked at Niyati and grinned. “Just the two of us.”

“It always has been,” she said cryptically.

Up the ladders and down the snakes the two pieces moved. On and on they played until it was nearing the middle of the afternoon.

Evan’s mom came outside. She lifted the plastic flap of the electrical outlet on the deck and plugged in a chocolate-colored radio with a movable antenna. She placed the radio on top of the deck rail, turned it on, and moved the dial until she found a soft rock station. Then she put on her canvas gloves and started pulling weeds from the flowerbeds. Next to her was a slat of marigolds from the nursery that she wanted to plant. The previous owners had been too old to maintain the flowerbeds so the dirt in the flowerbeds was overrun with weeds.

Evan’s dad pulled the lime-green lawnmower out of the shed in the backyard. He fired it up and started cutting the grass. The wheels of the lawnmower made parallel dents in the yard, and the dents looked darker than the grass between them.

The two children continued to play the game.

The sun’s beams intensified the vibrancy of the marigolds. And, just as the pink glamor on Coogee Beach at sunset on New Year’s Eve in 1993 would become as soothing as the sound of wind chimes, so the wind chimes in Evan’s backyard in 1979 soothed the mellowing sunlight that fell on the yellow of the marigolds.

Evan was having such a great time that he told Niyati, “This moment is so warm and comfortable that I want it to last forever.”

“Which moment?” Niyati asked.

“This one!” Evan said—and he rolled the die, advanced two spaces, landed on a snake’s head, heard Niyati laugh, moved his playing piece down the snake’s back to the bottom row and drew in a deep breath that filled his nostrils with the scent of the fresh-cut grass laced with the petrol fumes from the lime-green lawnmower, as a pickup truck rounded the corner near the house with all its windows rolled down and the throbbing beat of Journey’s “Wheel in the Sky” came pouring out of the truck’s speakers until the song’s attenuated sound waves receded in distance but were replicated and amplified in the twin speakers of the chocolate-colored radio on the deck rail that was tuned to the same radio station the driver of the truck had been listening to.

“Well,” Niyati said, “a lot of things happened in that moment. And maybe it was many moments and not just one.”

They broke off playing for an afternoon snack. Evan’s mom made peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, but Niyati said she didn’t eat peanut butter. So Evan ate both sandwiches while Niyati ate an orange. Then they washed their hands with the garden hose in the backyard and got back to the game. They played until sunset on the planet Earth where the sun rises in the west. Niyati’s mom came outside when it started to get dark. She went to the chain-link fence.

“Niyati,” she called out, “time for supper!”

Niyati sighed and gathered up the playing pieces and arranged them neatly in the teak box. She folded up the game board and put it in the box as well. Then she started to cry and took off her glasses and wiped her eyes.

“Why are you crying?” Evan asked.

“Because,” she said, “we’re moving tomorrow, so we’ll never learn how this game continues.”

On the last day of 1993, Evan said wistfully to the grown-up Niyati standing next to him on Coogee Beach: “I remember that day so vividly.”

—The passengers were starting to board the plane for the red-eye flight to Los Angeles. Evan rose from his chair and joined the queue, but he was still thinking about that “chance” meeting on the beach on New Year’s Eve.

He remembered sitting with Niyati on the sand. They talked for an hour and reminisced. He stretched out onto his right side. That must’ve been how the singularity got into his pocket. Niyati told him how she had graduated from MIT at 16 and was now an astrophysicist. He felt an inexplicable wave of fatigue. He rested his head on his right arm and looked up at her with a flirty grin.

“I can’t believe how beautiful you are,” Evan said. “Do you still wear glasses?”

“I wear contacts now,” she said.

He told her that he loved looking at her with the stars at her back, because it made her look like a metaphysical being. Then they both laughed at how stupid that sounded. She looked down at him in the moonlight.

“You grew up to become a very handsome man,” she said. She lightly brushed his cheek with the back of her hand.

And then it happened. Evan fell asleep—instantly—like that! When he awoke, Niyati was gone.

He wondered at first if it had all been some kind of crazy dream, but in the sand next to him was an impression from where she had been sitting. He rose and stood on the sand with the city’s lights behind him. He called Niyati’s name and strained his eyes, looking left and right. The beach was empty.

He retrieved his shoes and socks and put them back on. It took him 30 minutes to find a cab to take him back to the hotel. Once there, he went to his room, showered, dressed in his acid-washed jeans, went up to the rooftop lounge, put on a paper hat, and mingled with the guests until midnight. He sang “Old Ang Zine” as the fireworks lit up the sky over Sydney and illuminated the famous opera house.

But all he could think about was how New Year’s Eve 1993 would’ve been infinitely more enjoyable if Niyati had been there with him at the 5, 4, 3, 2, 1. Perhaps they would’ve kissed at midnight in the “here and now” which had now become the “there and then”—the first “moment” of 1994. It could’ve been the beginning of an incredible journey, the next move on that game board they stepped onto so long ago on that marigold-yellow summer day in 1979.

Continue to Chapter 2

Reads like a charm. Time floats by quite easily. That's what I like about your writing. It doesn't feel forced.

The scene in the back garden was written with such wondrous wistfulness that it got me quite emotional reading it 🥹

Really enjoying this, Daniel 🙂