The Hotel Rapunzel

The rusty castors of the service trolley creaked on the lemon-colored carpet stretching from the paternoster lift to the WC (pronounced veh-tsay) at the far end of the fourth-floor corridor. The flabby chambermaid pushing the cart removed the KARO cigarette from between moist lips and stubbed it out in the glass ashtray whose transparent bottom magnified the corner of the white sheet (now flecked gray) that it lay on. I’ll shove that corner under a mattress and no one’ll know the difference, Gertrude thought.

She windmilled her left arm to work out the sharp pain running up and down it, even as she relished the prospect of dying in that cheerless DDR hotel while pushing this symbol of a life wasted and hopes long since withered on the vine. The cart’s length and breadth were commensurate to her torso’s; and she reasoned that the rickety contraption would be an effective bier to wheel her out on should the need arise. Bear me off like a slain Spartan on his shield. And I hope to God that the paternoster lift gets stuck between floors to add to the hilarity.

The walls of the Hotel Rapunzel were covered with curling yellow wallpaper (faded to a drab mustard hue) that dated to the Yellow Nineties. The paper was adorned with Jugendstil panels showing scenes from the tale of the golden-haired damsel, whose curling blonde locks formed filigrees on the damask, resembling the gilt edges of an ex libris. Everything in this place is yellow, to include my uniform and nicotine-stained teeth

The hotel was a popular destination for closely-monitored apparatchiks from Eastern Bloc countries, UN officials, and the periodic Western academic who came to Eisenach to do visit Wartburg Castle, where the legendary Minstrel Wars of the High Middle Ages were said to have taken place, and where Martin Luther translated the New Testament during the Reformation. The theologian’s 500th birthday would be commemorated in the castle’s courtyard on 10 November 1983—only four months away—when State Council Chairman Erich Honecker would come down from Berlin to preside over the occasion.

Gertrude stopped the trolley before the door of room 4-C and rapped thrice. When no one answered, she inserted an iron schlüssel with jagged bittings into a keyhole. The latch clicked, the hinges groaned, and the fairy-tale door swung open to reveal an unhappy girl sitting at the table under the mullioned window.

“Why didn’t you answer when I knocked?” Gertrude said, waving her hand (almost) apologetically to disperse the acrid haze clouding her features.

The girl could not have been more than twelve. She was sulking, twirling the ends of a blonde ponytail. “My parents told me not to answer the door for strangers.”

“You speak German?”

“Yes.”

“You speak it like a fish head,” she said with a leer. “Like a northerner.”

“My parents are from Hamburg.”

“I see.” Gertrude stepped into the room and pointed to the messy sheets on the bed. “May I?”

The child nodded.

She removed the coverlet and stripped the bedclothes, taking these to the trolley and fetching clean linens from the base cabinet, so as not to use the dirty one on top. She presumed the cot in the corner was where the girl slept. So she made that up as well.

“If your parents are from Hamburg, you are too.”

“They’re not really my parents. I’m adopted.”

“Ah. . . That explains it.”

“Explains what?”

“Why you’re not close to them.”

“That’s a rude thing to say.” The girl looked away. “But I suppose it’s true.

“Where did they go?”

“To the castle.”

“Why didn’t they take you?”

“Because they don’t want me to be distracted from my studies by the tapestries and frescoes. Otherwise, I might get romantic ideas about knights and ladies.”

The girl handed Gertrude a notebook that lay open on the table before her.

The chambermaid flipped through the pages. “Numbers, graphs. . .”

“They want me to be an economist.”

“That sounds dreadful.”

“I think so too,” she said, taking the notebook. “But I do, in fact, enjoy mathematics. I have a knack for it.”

“You’re a strange child.”

“You’d be strange too if you weren’t allowed to read fun books or watch cartoons.”

“I did none of those things when I was growing up. But it didn’t make me strange.”

“Are you sure?”

Gertrude turned away and grinned.

In the silence the girl drummed her fingers on the table. “I’m not even allowed to read Michael Ende’s The Neverending Story,” she said. “All the kids at school are talking about it. But when I found a copy in the library and brought it home, father confiscated it.”

“I’ve never heard of the book.”

“It’s very popular. They’re making it into an English-language movie.”

“Good for them.”

“But it’s being filmed in Munich. With some parts filmed in Canada. . . Or maybe America. I can’t remember.”

“Do you need anything else?”

The girl lowered her eyes. “No, thank you.”

In the honey-tinted sunlight filtering through the window Gertrude saw the child’s lashes were glistening with tears. “Have you ever heard the story of Rapunzel?”

“Die Rapunzel (the lady) or das Rapunzel (the hotel)?”

“Both. They’re connected.”

“How so?”

“This hotel was where it all began?”

“Where what began?”

“The fairy tale.”

“I’ve never read it.”

“You can’t be serious.”

“My parents think fairy tales are nonsense. You see, I was born a prodigy. And when I was a child—”

“You’re still a child.”

The girl grimaced. “When I was a child, I had a private tutor who used only educational books to instruct me. By the time I was enrolled in the Gymnasium, we were reading belletristic literature.”

“What’s that?”

“Stuffy books, by people like Goethe and Herder.”

“Oh. . .”

“But I do recognize the name Rapunzel. I think it has something to do with a girl named after a species of bellflower—campanula repunculus.”

Gertrude went to the window, and pointed down. “Do you see that balcony on the third floor?”

“Yes.”

“This hotel was once a ducal palace. And that balcony looked out upon a garden surrounded on three sides by a wall. But the garden was not part of the palace, nor did it belong to the duke or his wife.”

“Who did it belong to?”

“A witch.”

The girl leaned forward in her chair. “Go on.”

“One day the duchess stood at the balcony, looking down longingly at a bed of rampion, which is to say rapunzel lettuce. She told her husband that her craving for it was so great that she would die if she could not taste it. So the next day, the duke put a ladder against the garden’s outer wall and climbed up it. There was a tree growing immediately on the other side that granted him access into the garden.

“When he had gathered up as much rampion as he could carry, he returned to the palace and gave it to his wife. When she tasted it, she said that she desired more of it and that she could not go on without a daily diet of the lettuce. The following morning the duke returned and fetched as much rampion as he could carry. But when he turned to leave, he was confronted by an ugly old witch named Mother Gothel.

“She asked him where he got off thinking he had the right to climb over her wall and steal her rapunzel. But when the duke explained that his wife could not live without it, the witch’s features softened. And with tears in her eyes she said, ‘You may take as much of the lettuce as you want. But you must give me your first-born child; and I shall raise her and love her as if she were my own.’

“Not long after this, the duchess conceived; and when she bore the duke a sweet daughter, the couple went to the church and christened the child Rapunzel. When they left, they handed the newborn to the witch, and never saw their daughter again.

“When Rapunzel was twelve years old, Mother Gothel, moved her to the top of a lofty tower in the Thuringian Forest. The tower had no stairs or lower chambers, because these had burned away in a conflagration long ago. As the girl grew older, her soft golden hair grew as well, until it became longer than the tower was high.

“Each morning Mother Gothel climbed down Rapunzel’s hair and spent the day in the walled garden gathering food for them to eat. And when she returned in the late afternoon, she would cry out: ‘Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair.’ And the girl’s tresses would fall from the open window and Mother Gothel would climb them.—”

“How did the witch and Rapunzel get up there in the first place?”

Gertrude’s brow contracted. “What do you mean?”

“If Mother Gothel had to climb Rapunzel’s hair to get into the room, how did she get Rapunzel up to the room the first time?”

“Magic.”

“Then why didn’t she use magic to go up and down the tower every day?”

“Because Rapunzel asked irritating questions like you’re doing, so Mother Gothel decided to punish her in this way.”

The girl began twisting the end of her ponytail again.

“Not only was Rapunzel the most beautiful woman in the land, she had a lovely voice, and sang as she went about her daily chores.

One day, the king’s son came walking by and heard her singing. He presumed it was a nightingale that had taken up lodging in the ruined tower and he resolved to find the bird so that he could capture it and bring it with him back to the castle. But when he stepped inside the tower, he saw nothing but ashes and scorched timbers lying about, and could find no way to the top.

“He heard the sound of someone approaching and ran into the bushes so he could observe what transpired from afar. He watched as an old woman cried out, ‘Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair.’ And when he saw the voluptuous golden ladder fall from the window and the hag climb up, he deduced that this must be the only way to the top.

“The next morning he returned, and saw the witch descending the tower by the same means. When the ladder was hoisted back up and had vanished over the sill, the prince placed himself squarely beneath it, and cried out: ‘Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair.’ Again the blonde locks fell; but this time it was the prince who climbed them. When he stepped inside, he gasped when he beheld the young lady.

“At first Rapunzel was frightened. She had never seen a man before, and this one was a rather toothsome specimen. The prince explained that he had been moved by her voice. But on seeing how lovely she was in the flesh, he could not go on without her. He asked her to be his wife. Rapunzel agreed and they kissed.

“She told the prince to bring her a silken rope each time he visited, so that she could weave a ladder so both of them could climb down it and escape. The prince’s daily visits went unnoticed for many months. And Rapunzel continued to weave the ladder, hiding it in a wooden chest that Mother Gothel never opened, because she respected Rapunzel’s privacy.

“But one night, Rapunzel accidentally said to Mother Gothel: ‘How is it that you are so heavy compared to the prince? When he visits me, he climbs up my hair and is up here in a trice.’ The witch flew into a rage. ‘You naughty girl,’ she said. She grabbed a pair of enchanted shears and cut off Rapunzel’s hair with a snip, snip, snip. Then she scraped every follicle from her scalp until it was as smooth as an egg.

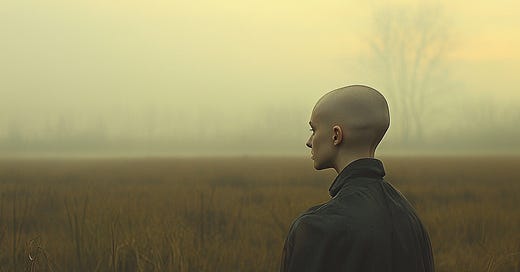

“By the same magic she had used to bring Rapunzel into the tower, Mother Gothel carried her off over the swaying trees of the Thurgingian Forest. She set her adopted daughter down on the willowed bank of a desolate marsh. Rapunzel’s hair never grew back; and she spent the remainder of her days in the misty twilight, singing of her sad fate and of the husband she had lost.”

“Well, that’s a depressing ending,” the girl remarked.

“It’s not over yet. . . On the same night that Mother Gothel Rapunzel away, she wove the girl’s hair into a thick cable. And when the prince came the next day and cried out ‘Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair,’ she cast the cable down. The prince climbed to the top. But when he had planted his feet firmly on the floorboards, he looked up and saw Mother Gothel standing before him.

“‘The cat ate the nightingale in the tower,’ the witch said. ‘See how its claws gouge out your eyes?’ Raising her hands, she raked the air with her claw-like nails, and the prince stepped back and fell from the tower. He grabbed hold of a prickly vine on the way down. But the dagger-sharp thorns plucked out his eyes. So he wandered for many years in the forest, alone and blind.

“He sustained himself on nuts and roots. And one day, he strayed into a marsh where, amidst the croaking of the frogs and the buzzing of the dragonflies, he heard what sounded like a nightingale. Rapunzel stood among the reeds, singing. On either side of her were the twins whom she had borne by the prince. When the young man recognized her voice, he knelt and encircled his arms around his beloved’s waist.

“Rapunzel bent low and shed two tears that fell in his empty eye-sockets, restoring his vision at once. The two embraced, and Rapunzel introduced him to his children. They returned to the castle, where lived happily ever after. But Rapunzel refused to wear a wig or otherwise conceal her head for the rest of her natural life. She outlived the prince and all of her children.

“When she died in her hundredth year, her body was placed on a marble slab in a high tower, which had no stairs leading up to it. Mother Gothel, having repented of the sins she had committed, cast one last spell with her dying breath. And Rapunzel’s golden hair (stolen long ago) was restored to the shriveled corpse in the high tower.”

When Gertrude concluded the tale, the girl touched her chin. “How did Rapunzel know the twins belonged to the prince?”

“Oh. . .” Gertrude dithered. “You’ll have to ask your parents. Enjoy your stay.”

The door slammed shut. And the castors of the service trolley creaked away.

Around lunchtime the next day, Gertrude found the girl in the ground-floor dining room, with its buffet of brittle cheeses, schwartenmagen (aspic), and a gray-white pudding that looked like a desert, but was actually pulverized carp. The girl wore an aquamarine beret and faced a harsh-featured woman who was making derisive comments about the state-sponsored newspaper she was leafing through—even as she cast worried glances at the empty chair that the paterfamilias had presumably only recently vacated.

There were no other guests in dining room, and the garden out back was bathed in bright sunlight. The girl smiled at Gertrude, who winked back before stepping outside for a smoke. Behind the leafy beech tree, she lit a cigarette and leaned against the bark.

There was a scuffling sound, followed by a grunt and sigh. Gertrude peered around the trunk, and saw the new bellhop exiting a wooden shed, and fidgeting with his belt. A man in a white shirt and plus fours stepped out, wiping his mouth.

He caught sight of Gertrude, and arrogantly looked away. He wandered over to a plot of vegetables surrounded by red bricks. He stooped down and started plucking the rampion.

“What are you doing?” Gertrude asked.

“My wife is ill. Her stomach is not used to the food here. She needs vitamins.”

His tone was confident, unconcerned. Gertrude regarded him with a baleful sneer. She took a deep drag from her cigarette.

Still kneeling, the man lifted his face up. “The garden’s part of the hotel, isn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“Then why are you looking at me like that?”

“Because I know what you were doing in the shed. This is not Hamburg.”

She saw the color drain from his face. She could tell he was surprised that she knew where he was from. She let the chilling reputation of the East Germany Stasi marinate in the man’s panicked mind, as she idly smoked away.

“I’m picking rampion for my wife,” he faltered. “I assumed that it was. . . free?”

He wants to know my price. “Nothing is free,” she said. She turned her gaze back to the hotel, and studied through the window the sad little girl at the dining-room table. Tears welled in her eyes. “I shall love her as if she were my own.”

“What are you talking about?” the man whispered.

But Gertrude did not respond. Something on the fourth floor had caught her attention. A thick blonde ponytail was oozing down from the windowsill of room 4-C. She searched for the girl in the dining room, but the only person there now was her mother. The man plucking rampion had vanished as well—as had the sun.

It was raining. Gertrude dropped her cigarette, and began to windmill her left arm in an effort to ease the lancing pain running up and down it.

A latch clicked, a hinge groaned, and the fairy-tale door swung open to reveal an empty room. So that’s when I died, Gertrude thought, looking down at her supine body lying next to the service trolley, skirt hiked up over knobby knees, fat calves sheathed in Dederon.

She mulled over the child apparition. And the more she thought about the ponytailed psychopomp, the more convinced she became that her encounter with the girl, combined with whatever she was experiencing now, was a compelling argument for the continuation of life after death. Otherwise, I would never have known about Michael Ende’s novel, The Neverending Story. Maybe I’ll read it, now that I have time.

The hotel manager suggested putting Gertrude’s corpse on the trolley so they could roll her to the paternoster lift at the end of the hall, since carrying her down the winding slick marble staircase into a lobby filling with curious onlookers was an open invitation to a world of unimaginable high jinks and knockabout comedy.

And two decades later, long after the Wall had fallen, a beautiful blonde mathematician from Hamburg sat (sun-kissed) at a beachside bar of a five-star resort in Mallorca, as a tanned Thuringian dropped two maraschino cherries in her second piña colada, and told her that he had never believed in ghosts until he worked as a bellhop at the Hotel Rapunzel in Eisenach.

“On my first day, one of the chambermaids, an old lady named Gertrude, died. We laid her corpse out on the service trolley and rolled her to the paternoster lift. The three of us were packed around the corpse like mackerels standing in a barrel when the lift got stuck between floors. An outburst of wheezy laughter was heard overhead; and the manager said, ‘I’d recognize Gertrude’s laugh anywhere.’”

Excellent retelling\adaptation

Magnificent!