Seven years ago I spent a week in Romania. A friend of mine had planned to join me but had to cancel at the last minute. I met my driver at the airport. As he was taking my luggage, I asked if he could drive me to the Monastery of Snagov before dropping me off at the hotel in Bucharest. He said this wouldn’t be a problem and that it was in fact a good idea, since by the time we left the monastery traffic into the capital would be light.

Romania is a beautiful country with a landscape that is in many ways redolent of the rolling hills of the Bluegrass State. Within an hour we arrived at the monastery’s parking lot, a muddy space overgrown with grass and weeds surrounded by a split-rail fence. There may have been cows in the adjacent pasture, but I can’t remember for sure. The older I get these undeveloped stopping points at the entrances to state fairs, national parks, and prehistoric ruins become a blur.

The Monastery of Snagov is situated on an island in a reedy lake. Local tradition holds that Vlad Țepeș, the Voivode of Wallachia, known throughout the world as Count Dracula, is buried there. Access to the island (at that time) was via a zigzagging aluminum bridge which had been assembled to replace a former bridge that my driver said had recently been demolished.

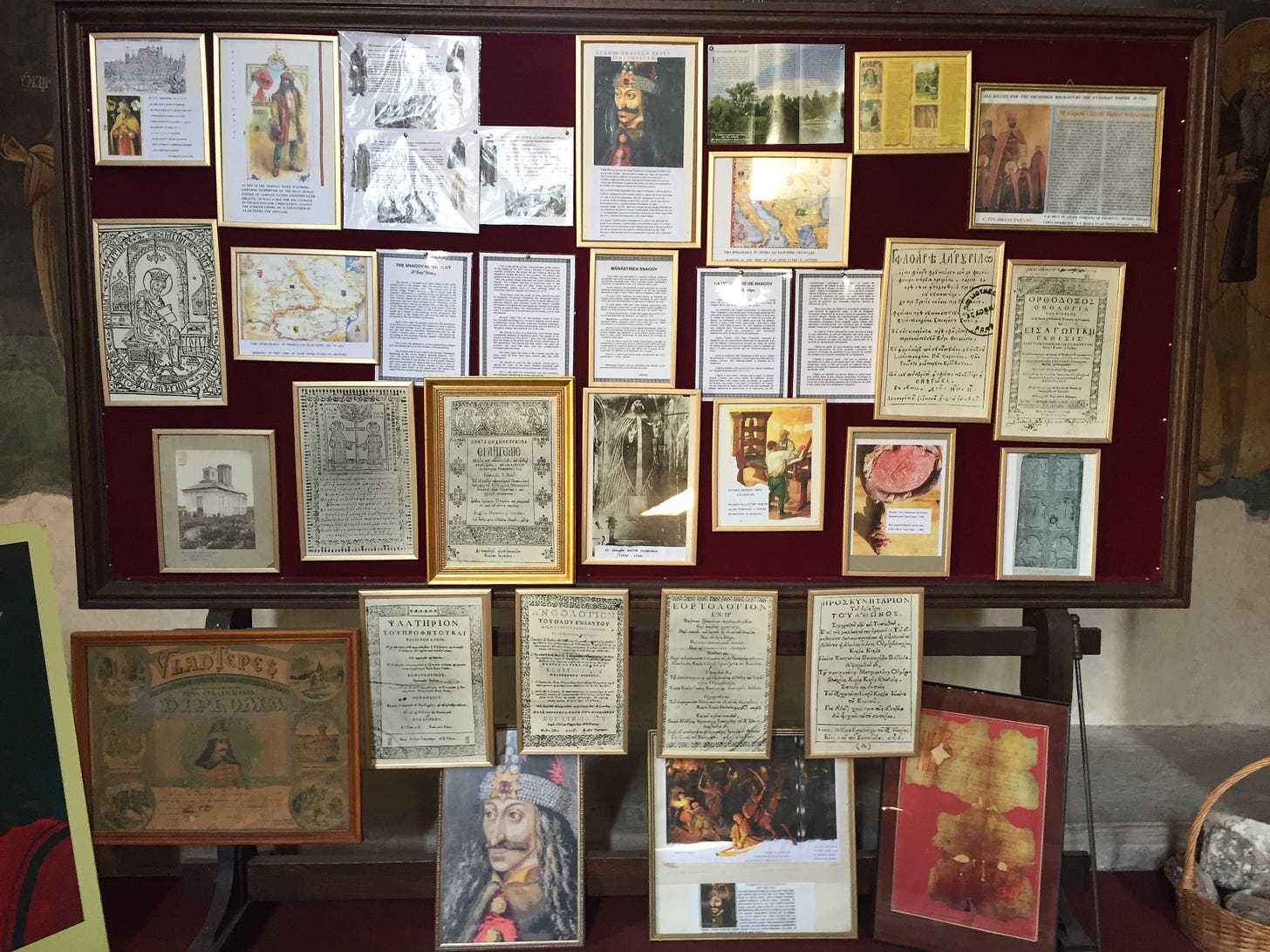

The monastery is not large. The tomb of Dracula is in a chapel built in the Byzantine style. Two Orthodox priests were talking to each other when we entered. They ignored us. The younger priest was wearing a smock over his cassock and doing masonry work on the north wall. On a peg board there were placards and wooden holders stuffed with glossy brochures in French, German, Italian, Romanian, Russian, and ungrammatical English.

I asked if I could take pictures. Both priests nodded, but the older one added gravely “Just no flashes.” As he said this, my driver took a selfie of himself in front of a fresco of St. George and his camera flashed. The priest pretended not to notice.

I pointed to the slab on floor that marked the grave of Vlad Țepeș and said, “So that’s the—”

“He was a great man!” the old priest said. Then he turned away and spoke rapidly to the younger priest in Romanian. I heard the word turiştilor. Since I don’t understand Romanian, I just assumed he was complaining about how Western tourists always came to see the grave of Vlad Țepeș, whom they believed to be a vampire.

In Romanian tradition, Vlad the Impaler is a Solomonic figure, a wise folk hero who treated his subjects with dignity, humility, and respect. He is revered as a paladin who helped preserve the eastern frontiers of “Christendom” (a term not much in use these days) from the violent onslaught of “the Heathen Turk” (another phrase that’s gone the way of the Dodo). The truth behind the legend is much more complicated and far too involved to go into here. It is the story of the fall of Constantinople in 1453, of infighting among Germanic and Hungarian noblemen over ill-defined borders on the continent of Europe (which is more of an Asian peninsula than a continent), and of the young son of Vlad Dracul, who spent several years as a hostage—some say a willing one—in the court of the Ottoman Sultan Murad II.

But this essay isn’t about Vlad Țepeș. It’s about that famous “image” of him—an image so popular that even children recognize it on sight. It appears on T-shirts and postcards, and is now so popular on social media that it has become a recurring meme, a meme as immortal as Bram Stoker’s grisly creation: “The Blood of Atilla flows in these veins!” On the Count’s grave was an icon of Vlad Țepeș based on that portrait. And you will notice that the placards on the peg-board also made liberal use of the image.

I had not come to Romania to go vampire hunting. I was actually doing some research into the life and times of former Romanian dictator, Nicolae Ceaușescu. But, since I was going to be in the country for a week, I thought I’d visit a few of the tourist traps associated with Vlad Țepeș and make a mental note of how many times that image cropped up. It’s literally everywhere. In Bucharest, there is a bust of Vlad Țepeș based on the painting. The bust stands on a pillar amidst a few smashed Medieval ruins in the center of the old town. Then there’s Sibiu (ancient Hermannstadt), which should probably be better known among Dracula aficionados than it currently is.

If you want to experience an interesting potpourri of vampire kitsch and late 20th century commercialism, I would recommend a stroll through the open-air souvenir market at the base of Bran Castle—the so-called “Castle Dracula.”

What makes Castle Dracula funny to me is that there’s no proof the Count ever set foot in it.—He may have been there?…Perhaps? I mean, it was under his jurisdiction and whatnot, but, again, there’s no documentary evidence that I’m aware of proving that he was ever there. (But then there are some scholars who dispute claims Vlad Țepeș is interred in the “Tomb of Dracula” on the Island of Snagov.) Since the curators running Bran Castle don’t want visitors to leave without a thrill, they’ve stocked every room of it with wax figurines, macabre dioramas, and authentically ancient instruments of torture imported from the dungeons of other Eastern European Burgs and Grads.

I’m going to fast-forward to the early spring of 2016. I am speeding through the foothills of the Tyrolean Alps aboard an ÖBB express from Vienna to Innsbruck. This is my fifth visit to Innsbruck and my third to Schloss Ambras, a Renaissance castle housing one of the most interesting cabinets of curiosities in the world. The collection was assembled by the eccentric Archduke Ferdinand II of Vorderösterreich (1529–1595). I was heading to the castle to see the famous portrait of Vlad Țepeș.

The first time I visited the castle was before the invention of digital cameras…In fact, it was before the Berlin Wall fell. The second time I visited the castle was in the summer of 2013 and everything was green. (See above). During that visit, I practically sprinted to the cabinet of curiosities, located on the second floor of a separate building within the palace complex. (See below.) When I reached the gallery where the portrait of Count Dracula was supposed to be, I was met with a “Sorry Folks!” placard indicating the portrait was currently on loan to another museum. I was fuming, but I vowed I would return again to photograph it.

On my third trip to Innsbruck, I was scheduled to be in town for two nights. I hired a driver to take me up to the castle. The buses going up and down the hill were infrequent at that time of the year. I paid the driver handsomely to wait for me, telling him that I would probably be no more than two hours.

Before seeing the painting, I wanted to enjoy a Viennese coffee and Sachertorte in the castle’s world-renowned Ferdinand Café. I bought my ticket to the castle and went to the café. I sat there reading a rare book I picked up earlier that day at an antiquarian bookstore in Innsbruck. The book was by Emil Lucka (1877–1941) called Die Jungfernprobe (The Maiden’s Test). The story is a dark fantasy, published in 1926. The book is full of creepy woodcuts by an artist named Hugo Rényi. I buy books with woodcuts like these on the off chance that I might be the sole owner of these works of art, assuming the originals are lost or perished after Second World War.

As I was reading my book, there was a man on the other side of the restaurant who was being boorish and was obviously drunk. When I finished my coffee, I paid the bill and left. I made my way up the steps leading to the cabinet of curiosities. There was a layer of snow on the balustrade. That’s how cold it was in the Tyrol that day. I opened the sturdy wooden door to the cabinet of curiosities and was pleased to discover that it was empty. I would be on my own. The room was unheated and I could see my breath. The floorboards creaked and groaned.

If you’ve never been into one of these collections, it’s like stepping into an Aladdin’s cave. You will find sacred works of art, such as little scenes of the Crucifixion on Golgotha carved out of red coral. Overhead you may discover the stuffed carcasses of sharks and alligators. The mummified hand of a Coptic monk will rest next to a Uralic amulet made of pewter and amber.

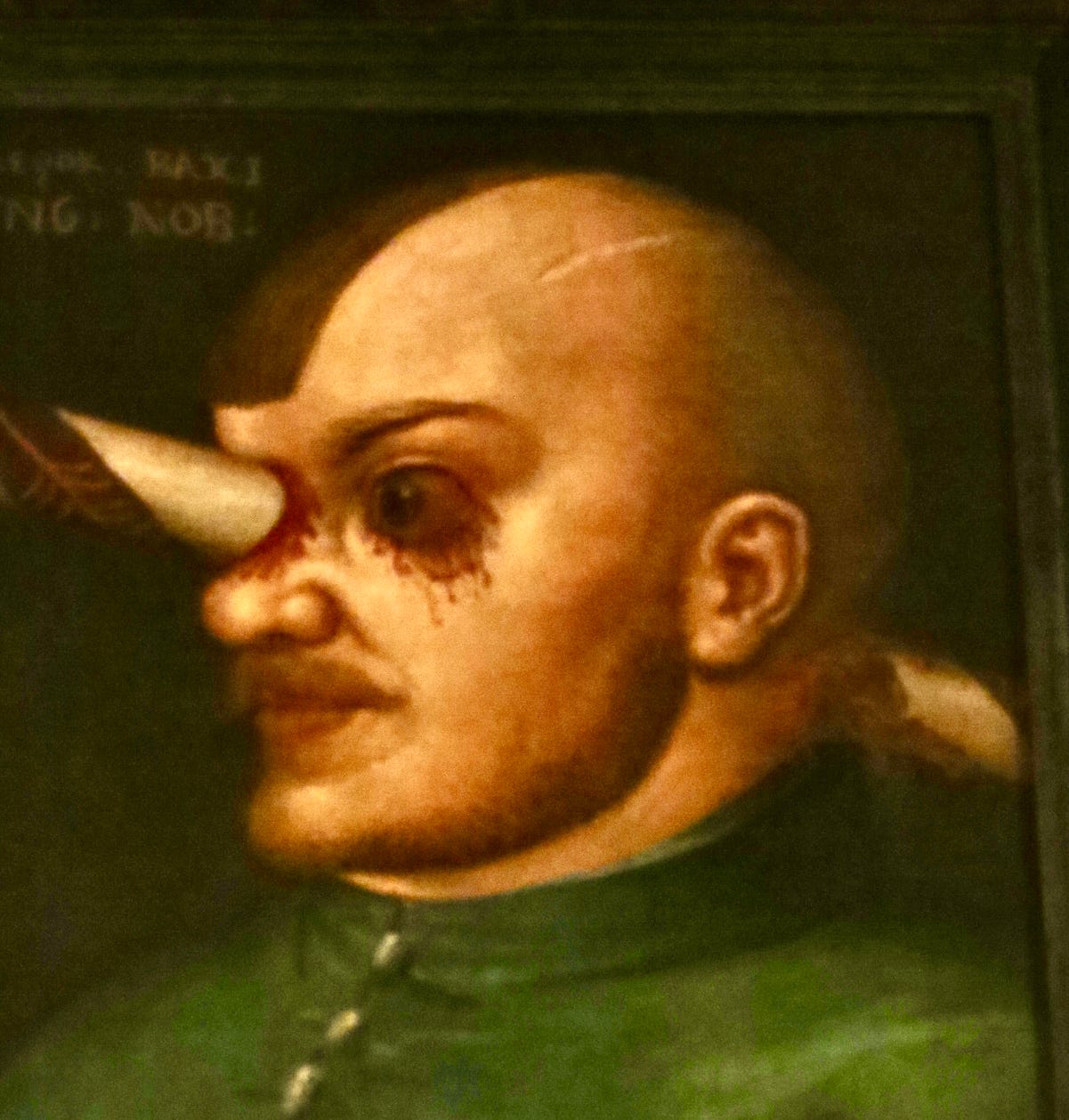

The portrait of Dracula is saved for last. It’s displayed at the back of the cabinet of curiosities on a wall next to portraits of people with deformities, disabilities, or medical conditions. It is like something out of the Grand Guignol. Archduke Ferdinand brought these people to Schloss Ambras to live—not as slaves (even though that’s essentially what they were) but as objects of contemplation and amusement for him and his guests. One of the portraits is of a man whose brain was pierced by a lance during a joust. He somehow survived, but with his cognitive faculties severely impaired and with blood issuing continually from his remaining, bulging eye. There were portraits of a family from the Canary Islands whose entire bodies were covered with hair.

And there he was: Vlad Țepeș in that famous portrait by an anonymous artist. The painting is believed to be based on a copy of a contemporary portrait of the Count made during his lifetime. I was standing in front of the painting when I heard the door behind me open. I didn’t turn to see who it was, but I could hear that it was the drunkard from the café. He was making exaggerated hemming and hawing sounds as he made his way up and down the aisles. I rolled my eyes.

I turned around and tried to position myself in a way so that I could take a selfie with the portrait of Vlad Țepeș behind me. The man was walking toward me, so I lowered my phone. Suddenly—and this still pisses me off to this day—he grabbed my phone out of my hand and said, “Here, I’ll take your picture.” That was the first time I looked at him. He was wearing a black leather jacket—and that jacket stirred something at the back of my mind. And then all of a sudden the memory hit me like a hammer fall. It was almost Proustian.

Two years prior, I was in Belgrade for a weekend. I hired a guide to take me to Niš: ancient Niassos, where Constantine the Great was born. On the way back, I asked him to stop at the Serbian Orthodox Monastery of Ravanica. He parked his car in another one of those undeveloped parking lots like the one at Snagov, and we walked to the monastery.

It was a gray and drizzly afternoon. We entered the church and I photographed some of the frescos and icons. Suddenly, the doors of the church flew open and three men walked in. All of them wore black leather jackets. The eldest man, the leader, had a shock of white hair and was wearing sunglasses. He seemed to be in his 60s or 70s. He took his place before the iconostasis and started to pray. The two men standing behind him, obviously his entourage, waited with their arms folded. My guide said, “Let’s go, please.” He ushered me out of the church. “Who was that?” I asked. He replied, “He’s a bad man. He does evil things and then comes here and prays, like it’ll make it better.” And then I saw that there were three mercedes parked in the same parking lot. And the engines of all of them were running. There were four men lounging about, smoking.

My guide drove away in silence. I looked over at him and saw that he had wiped a tear from his eye. His face was red, haunted. I looked away. It was not my place to ask what kind of connection there was between my driver and the man who had entered the church to pray. The guide asked me, “Do you want to see anything else before I take you back to your hotel?”—“No, thank you.” I replied.

The drunkard took a photograph of me and then handed me my phone.

“Glaubst Du an Vampire (Do you believe in vampires)?” he asked, grinning and pointing at the portrait of Count Dracula.

“Natürlich (of course),” I said. And my eyes fell again on his black leather jacket. “Die Vampire sind überall (Vampires are everywhere).”

Whether it was the brusqueness of my voice or the way I looked at him that caused him to react as he did, I will never know. But the drunkard abruptly turned away from me, and walked out of the cabinet of curiosities.

I love the way you tell a story, especially that final line - Vampires are everywhere.

Wow, vampires are everywhere, indeed.