Book II, Chapter 7: The Judge’s House

List of Chapters | Previous Chapter

It was the night after the rabid dogs had invaded the stable. Benedikt the ostler sat in the center of the carriage house’s living room, entertaining the assembly by reading aloud from Theodor Fontaine’s novel, Ein Sommer in London. The room’s table was at his elbow so that he could read by the lantern’s light. Alternating the pitch of his voice between characters, his animated recitation grew livelier as the tale progressed. But he often stumbled, or had to reread passages, since he was slowly going blind.

Hermann, who was only half-listening to the story, leaned against the wall and contemplated Walter, who lay stretched out on the couch, head pillowed on Monika’s lap.

Benedikt concluded the third chapter and had just launched into the fourth when Monika signified by a tender gesture that “Florian” had fallen asleep. She woke the boy and asked him if he was ready to go to bed. The orphan nodded and rose from the couch. Monika lead him to his room to tuck him in.

Benedikt ignored their departure, silently mouthing the initial paragraphs of the subsequent chapter so that they would be fresh in his mind for the next reading, whether that took place tomorrow or the day after.

Hermann stretched and yawned. “Your wife is very good with children.”

“Yes,” the ostler replied. He snapped the book shut, stood up and grabbed the lamp from the table. “We should check on the horses before turning in.”

They drew their coats on and headed downstairs.

Hermann and Walter had acquired multiple changes of clothes since their arrival at the coach inn the previous month. Most of these had been donated by the Eltzbachers, including the warm coat he now wore. But some of the articles had been purchased in the unnamed village that lay behind inn’s stables. Although the village had no name and appeared only on a few military maps, the farmers in the area sometimes referred to it as Am Haus Löringhof (near Löringhof House), due to a medieval castle by that name, the ruins of which lay southwest of it.

When they reached the bottom of the steps Hermann found himself looking back on those blissful years he had spent as a cartwright at the Landecker Werke. With a critical eye, he appraised the neglected wheels of the Eltzbachers’ landau and gig. The landau had not been used for many years because it needed to be pulled by two horses and the Eltzbachers only had one, although two were currently in the stable. It was an aspect of the coach inn’s operations that Hermann still found mystifying.

Frau Eltzbacher maintained contracts with several firms in the region that were permitted, at a fixed rate, to stable their horses at the inn between relays. It was up to Benedikt as ostler to take care of the animals. If a horse arrived sick, the ostler did what he could to nurse it back to health. If its condition was terminal, the firm was notified and a representative hastened to the inn to fetch the beast and take it directly to the glue works before it died, which was cheaper prospect than hiring a knacker to haul the carcass away.

Benedikt opened the stable’s doors and stepped in. He raised the lantern and examined the dirt floor, which still black from the mad dogs’ blood.

“Hold this,” he said, handing Hermann the lantern.

“How long have you and Monika been married?”

“It’s none of your business.”

“I wish you wouldn’t talk to me like I’m an adversary. Upstairs I meant no offense when I insinuated that your wife would make a wonderful mother. I marvel the two of you don’t have children.”

Benedikt wheeled around and regarded Hermann with an expression of curiosity, as if he wanted to divulge a secret to him but was unsure if he could trust the man. But out of nowhere he began to speak.

“Monika’s parents died shortly after her birth. She was raised by a reclusive judge, a widower, who lived in a crumbling mansion outside of Dresden. He had not sat on a bench in years, due to the severity by which he had prosecuted alleged insurrectionists in the wake of ’48.

“He was said to have tortured and hanged nearly a hundred men and women, supposed collaborators—the evidence against whom was scant if it existed at all. There were rumors that he had accepted substantial bribes from noblemen who sought to settle old scores, now that the chaos had ended and order had been restored. He was removed from his office by a faction of courtiers affiliated with Prince Frederick Augustus II of Saxony.

“Back then I was an itinerant schoolmaster—‘down on his luck,’ so to speak. I found work where I could, as a stablehand, a street sweep . . . a rat-catcher.”

At that, Benedikt seized a spade from the stable walls and with a heavy stroke dispatched a rat. The clang of spade’s iron against the hard dirt caused one the stallions to nicker in its pen. Benedikt placed the spade back on the wall and resumed his narrative.

“I lived over a chandler’s shop in Dresden’s marketplace, a rookery whose shuttered windows opened out onto die Steinerne Glocke (the Stone Bell), that curvaceous dome crowning the magnificent Frauenkirche, whose 43-stop organ had been played by none other than the musical savant of Eisenach, Johann Sebastian Bach.

“My landlord was a shifty-eyed criminal, who ran a gang of smugglers and thieves that operated on both banks of the Elbe.

“Tacked to the notice board of a public house I frequented was an advertisement seeking a private tutor for a young girl of means who lived under the care of ‘a loving uncle’ deep in the Saxon wilderness. Petitioners were directed to the judge’s agent, a clerk who ran a counting house on the left bank of the Elbe.

“I crossed the Augustus Bridge and bent my steps to the address indicated, where I met a fit young man, approximately my age, who had been educated at Leipzig. My knowledge of both Latin and the rudiments of arithmetic so impressed him that I was hired on the spot.

“He told me that the job required me to reside at the mansion. He commanded me to return to the counting house in three days. He pressed into my hand a coin purse containing a modest advance, warning me that I must keep my promise and not to flee with the money: ‘You’ve made a pact with the judge, who has even more reach than the Devil.’

“When I notified my esurient landlord that I would be moving out, he spontaneously computed an outrageous sum that he said I owed. He threatened that, if I did not settle my debt in its entirety before my departure, I might find myself face down in a pit. Around him stood his retainers, who shook me down and found the coin purse. He took everything I had.

“‘Consider your debt paid,’ he laughed. ‘Feel free to grab your belongings before you leave. I know you have nothing of value in the room. My men have already checked.’

“My prized possession was the Latin primer that Monika pointed out to you on the night of your arrival. It was the book that I was taught from and I have kept it with me ever since in memory of man who instructed me. I took it and a change of clothes, and spat on my landlord’s boots as I left.

“My last two nights in Dresden, were spent under the old bridge, hungry and exposed to the cold October winds. I returned to the counting house on the third day, as the judge’s agent bade me do. The man met me in front of the counting house’s padlocked door. He directed me to board a small leaky boat moored on the quay close by.

“The pilot stepped into the boat, wearing a straw hat over a black hood, which he had pulled down low. He directed us to sit on the bow plank, as he took up the oars in the center of the boat and sculled the craft in silence down the Elbe’s placid stream. As the city passed behind us an eerie mist rose up whose thin vapors enveloped the weird trees lining the mossy banks.

“My young guide hung the lantern on a hook at the prow, and leaned back, elbow akimbo on the gunnel, explaining to me that, during my sojourn, I would be sharing a room in the mansion with an elderly footman, the judge’s only remaining servant. At nightfall, we entered a dark tributary where a boathouse loomed into sight. Beyond it, through the birches and white elms, winked the dim lights of the decaying mansion’s many windows.

“‘Take note of what I am about to tell you,’ the agent said. ‘So long as you live under the judge’s roof, you must never touch, even inadvertently, his niece. If he catches you in the act.—Nay, if he senses that an intimacy has developed between the two of you, he will have you gelded and cast into the river with a stone about your neck.’

“‘I have no such designs!’ I protested. ‘I am poor, but I was raised Christian and will not be taken for a villain.’

“The guide smiled and pointed casually over the edge of the boat. I squinted in the darkness and detected a lumpen shape drifting toward us through the reeds. In the lantern’s diffused light I saw what it was: the bloated corpse of my erstwhile landlord.

“‘That would have been you,’ the young man said, ‘if you had tried to run away with the money.’

“There was a dull thud as the boat’s keel bumped up against the body. Slowly the vessel veered into the boathouse’s gloomy interior. No sooner had it stopped at the edge of the rotting planks than the pilot could be heard chuckling. ‘I like this one’s spirit,’ he said. ‘I feel that I can trust him.’—It was the judge!

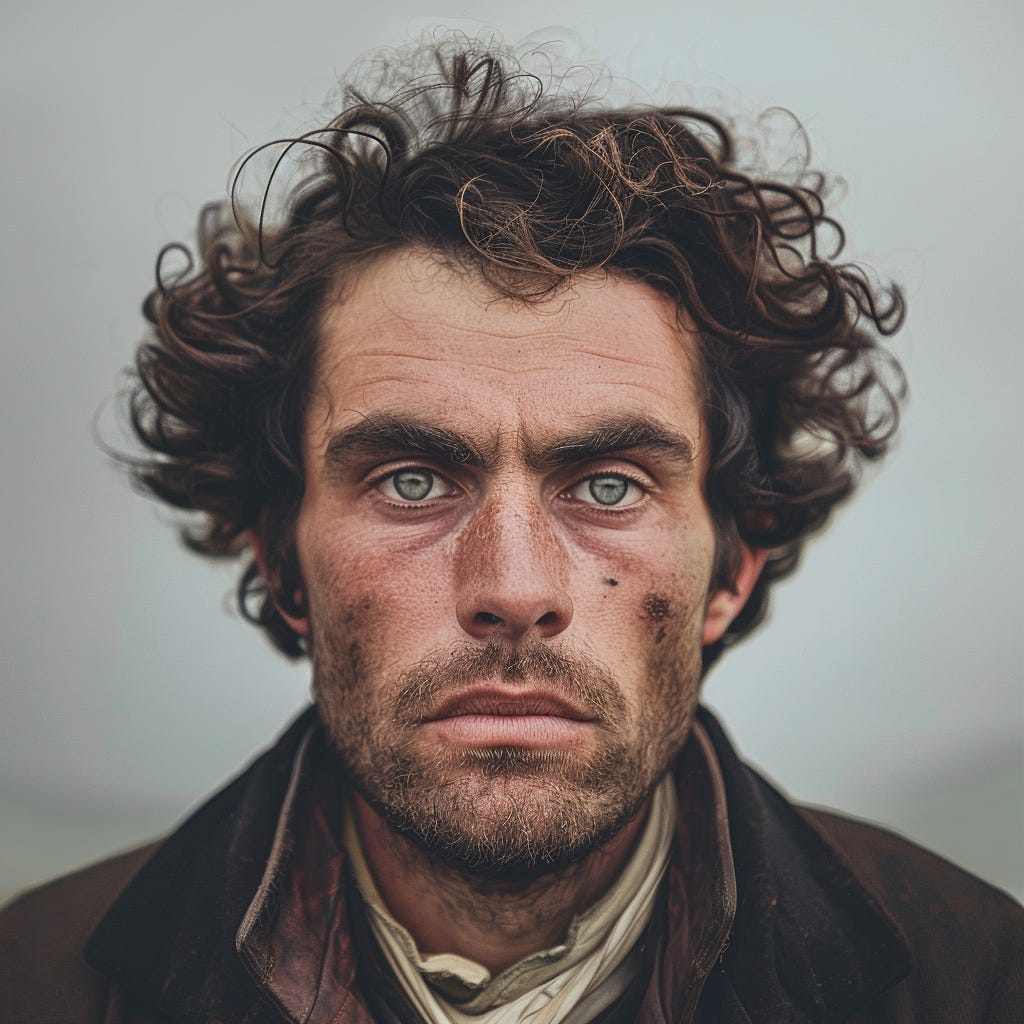

“He exited the boat, threw off the straw had and pulled back his hood. I recoiled at his palsied, ulcerous face. Beneath his chin hung a bulbous goiter like a milch cow’s dewlap. My instinct told me that I must show no fear, that I must remain firm and entirely resolute. So I joined my employer on the boathouse’s creaking boards and kept my chin high.

“Meanwhile, the young agent had moved to the center of the boat, taken up the oars and began to scull away. His job here was done. As the light dangling from the prow’s hook vanished, the judge lit the wick of a lamp on a table by the door. Then he reached into his pocket and removed a coin purse, casting it to me with a grin. ‘You seem to have misplaced your advance,’ he said.”

Benedikt wiped the back of his neck. “You may think me a fool for not fleeing that very night. But I was desperate. I was afraid. And yet, there was an unChristian part of me that was gratified at how the judge had laid a retributive lash upon the back of my enemy, that hateful landlord.”

Benedikt looked coldly at Hermann, who wondered if the ostler perceived him as an enemy. As if reading his thoughts, Benedikt nodded and made a clicking noise with his mouth. He walked over to the pens, where both stallions appeared. He scratched the ear of one, and spoke with his face turned to the other.

“The venerable footman met us at the door, and I was conducted into a salon where my first encounter with Monika took place. I maintained five paces between us, bowing respectfully to the girl. I had ever laid eyes on a more unhappy creature in my life.

“Over the days that followed I could hear the judge breathing and coughing behind the walls, all of which were hollow with secret passages through which he could observe my interactions with his niece—through a myriad of apertures concealed in the wallpaper or hidden away in the brass fixtures and sconces.

“How shall I describe to you the decor of the mansion? It was filled with porcelain figurines the judge had privately commissioned from the nearby factory in Meissen. He thought it would be amusing to amass a collection of figurines representing jubilant men and women, with palsied leers and ulcerous faces—with goiters at their necks and other deformities resembling his own. Hundreds, if not thousands of these, were displayed on shelves on every floor and in every room. Behind them were cracked and distorted mirrors, positioned in such a way so as to enhance and multiply their grotesqueness.

“My student’s knowledge of Latin far exceeded my own. She was—is a prodigy. But she chooses to hide her native talents behind a veneer of rural simplicity. She told you that I taught her how to construe Latin. That is untrue. From the moment she could read German, the girl lost herself in her uncle’s books, teaching herself the rudiments of Latin, Italian, and French. The library was the only place she felt happy. It was the only place where she could escape from the horrors that compassed her round in that crumbling abode.

“I kept my distance, lecturing to her from across the room, or standing well behind her as she read from a book—for in those days I could still read fine print from afar.

“One time, at the supper table, Monika’s fingers lightly brushed mine as she passed the salt cellar to me. Both of us froze. But the judge, having witnessed this, seemed unperturbed. He even weighed in, nonchalantly, on an obscure grammatical point concerning Latin verbal declensions that my pupil and I had been discussing earlier that day.”

Benedikt’s shoulders slumped and he turned to face Hermann, tears brimming in his eyes. “As that winter passed into spring, I began to suspect by the way the judge addressed Monika—by the way he . . . touched her—that she had been ill used by him. Do you understand what I mean?”

Hermann blushed and looked away.

“It was a rainy April morning. The judge had contracted a cold that had confined him to his bed. My pupil and I sat across from each other in the mansion’s rococo library. We sat closer to each other than we had ever dared do before. Between us lay an open volume of Ovid’s Metamorphoses.

“The black clouds hanging over the Saxon wilderness without the windows deepened the shadows within. Misery hung on my sweet girl’s brow. A strip of gauze was wrapped about her wrist.

“Knowing that the illiterate footman had taken up his master’s position behind the wall and was eavesdropping on us, I spoke in classical Latin, asking her if there was a message that she wished to communicate to me.

“The girl’s eyes turned to steel as she ran her fingers over the lines of the poem describing how Lycaon, king of Arcadia, murdered his slave and served up the boy’s cooked flesh to Jove in order to test whether the guest in his house was indeed divine as he was rumored to be. Seeing through the ploy, Jove punishes the Arcadian king by transforming him into a wolflike man. For it is Lycaon who gave his name to the first Lycanthropos, werewolf . . .”

The ostler glanced knowingly at Hermann, whose features had hardened in the wavering light of the lantern’s flickering flame.

“It was then that Monika removed the gauze around her wrist and revealed to me the livid marks where a man’s teeth had torn her flesh.”

Hermann stepped back and exhaled. He felt an urgent need to force the ostler to conclude his story. “Then you took her away from that place?”

“Yes.”

“What became of her uncle?”

“I went to his bedside and plunged a jagged knife into his goiter. Monika stood at the door and watched, unmoved. I was drenched in his blood.”

Hermann stared at the ostler in awe.

“She assured me that her uncle’s doddering servant had known nothing of what his master had done to her, and so I spared him. We gathered up some food and a few personal items, along with two silver candlesticks which we planned to sell. But we were afraid that too many items would only burden us in our flight.

“The footman saw me and ran to his master’s corpse. ‘Murder! Murder!’ he cried out, knowing full well that it was I who had committed the deed. But there was no one else in the house to hear the servant’s pleas.

“The judge kept carrier pigeons on the grounds, but the footman could neither read nor write and would not be able to use these to alert the authorities in Dresden of what had taken place. The mansion was so remote that it would not be until one of the boats making its weekly deliveries arrived at the estate before anyone would learn from the old man what had happened.

“We fled downriver in one of the judge’s boats. And a few miles beyond a Saxon village we had passed, we drew the boat ashore and hid it amid the trees. From there, we made our way by land to Leipzig, where we sold the silver and used the money to emigrate to the Rhineland. Neither my wife nor I have ever changed our names—as some fugitives are wont to do.”

Benedikt smiled enigmatically at Hermann.

“I told her once we arrived in Cologne that I would not compel her to stay with me—that I would do all in my power to see her settled in a place where she would be safe and where she would be able to thrive on her own. She told me that she would never feel safe without me. When she grew to womanhood, we betrothed. The bond of affection that my wife and I share can never be severed, even unto death.”

“Why have you told me this story?”

“Because you said that you marveled that Monika and I do not have children. The abuse she suffered at the hands of her uncle has made the touch of any man insufferable to her. We sleep in a room behind a locked door on the upper floor of the carriage house. But within that room are two narrow beds that stand well apart from each other.”

Benedikt took the lantern from Hermann’s hand. Together the men left the stable and returned to the carriage house.

Catching up on Chap 23-24. Still reading and still fascinated! Particularly anxious to understand what it is that horrified the ostler when he looked at Hermann after the dog attack... I must be patient I suppose!