Book II, Chapter 25: The Keepsake

List of Chapters | Previous Chapter

Exiting his cottage one bright February morning, Abner Eltzbacher slipped on the doorstep and landed supine on the ice. Though he’d broken no bones, his body was covered in bruises—“like rotting fruit,” he observed. Confined to his bed, the old man had taken to reciting from memory the more sepulchral stanzas from Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” apparently to his own amusement since no one around him understood English, save the village doctor who dropped by daily to check on him (but who had never warmed to “the harsh numbers of Albion’s versifiers”).

Frau Eltzbacher asked “Florian” (the only name she knew Walter by) if he would move into the cottage temporarily to keep an eye on her husband so that she and Monika could tend to the inn’s guests. Knowing how important Mürrisch was to the boy, she sweetened the proposal by telling him he could bring the cat too. The combined presence of the orphan and one-eyed feline had such a salutary effect on the old man’s disposition that he spent his waking hours, sitting up in bed teaching Walter his letters, as the tomcat snuggled contentedly on his lap.

With Walter out of the carriage, it was only Hermann, Benedikt, and Monika who remained on the day the incident took place that would upend the Hermann’s life once more, and lead him to realize that the accommodating situation he had found himself in since fleeing the workhouse in Cronenberg might soon be drawing to its end.

Benedikt had taken ill the night before it happened. So it had been up to Hermann to pick up the slack. Having carried a rick of cord wood into the coach inn and depositing it by the fireplace in the common room, he’d eaten a cold repast in the kitchen while Monika and Elischewa fussed over the diced pork and cabbage for the guests’ supper. But even as she worked Monika cast worried glances in the direction of the carriage house where her husband was sleeping.

By mid afternoon, the sunlight was fading fast. The pewter clouds had dulled to a leaden hue, portending in Hermann’s mind the onset of heavy snowfall. He was alone in the stable and had just finished feeding the four horses on loan from the coach firm in Speyer, when Monika cracked open the door, lantern in hand, and said, “Moritz, please hurry. Benedikt’s raving.”

“What?” He grabbed his lantern from the farrier stool and followed her outside, latching the door behind him so that it did not blow open in his absence.

Leaning into the wind, they crossed the frozen ground as fast as they could. They slipped through the side door into the carriage house.

Hermann noticed a light flickering behind the tarp-covered chaise. The oilcloth hanging in front of the galvanized tub had been flung aside. A lantern hanging on a wall hook illumined a neglected corner where gardening implements and other tools and apparatus were stored. Monika had laid out towels from upstairs on an overturned crate next to the tub, which was partially filled with freezing well water. “He told me to prepare his bath,” she said, answering Hermann’s questioning look. “It’s all so strange!”

“Where’s Florian?”

“With Abner in the cottage.”

An agonized cry broke out from the upper story and the two ran up the steps, reaching the living room within seconds. Tallow candles flickered in their dishes on the round table, while two pots of water boiled over on the Franklin stove. Black smoke rolled out of a gap in the vertical pipe that Benedikt and Hermann had been meaning to fix. The soot settled on the bookshelves, sofa, and window sills. Clad only in his nightshirt, Benedikt fed wood chips into the firebox.

“What are you doing?!” Hermann said, slamming the hatch. “You’re going to burn the place down!”

The ostler confronted him, drenched in sweat. His eyes were swollen, his face empurpled.

Hermann seized him by the shoulders. “What’s wrong, Brother? Tell me!”

Benedikt called out to Monika: “My love, leave us. What I have to say to him is not for your ears.”

“Benedikt—”

“Go!” he exclaimed, pointing to the frowning walls of the coach inn through the smudged panes. “I will not speak to him until I see the kitchen door shut behind you.” He looked up at the ceiling, as if he sensing something in the rafters.

Monika tore her hair. “I’m scared!”

The voice Benedikt answered her in was not his own. “If you don’t do as he says, he dies.” But his tone softened again. “But if you obey me, Monika, I may yet live.”

The Saxon woman recoiled, aghast. Without another word, she fled the room, abandoning her lantern on the table. From the window, Hermann watched her run out of the carriage house. She lost her footing near the gable-roofed well, but rose again. Throwing open the back door, she slammed it shut behind her. Hermann turned to Benedikt in mute entreaty.

“The demon is pressing me to tell you the rest of the tale,” Benedikt said.

Hermann had never seen the man so discomposed—so out of sorts. But Benedikt had not been the same since their return from Kohlendorf two weeks prior. After their hearty meal at the restaurant, they had returned to the luxury hotel where they were staying. Hermann woke the next morning, staring up at the canopy of the broad bed they had shared. When he sat up, he saw Benedikt pacing the room in a state of almost feral agitation.

Before Hermann could ask what was the matter, the grizzled man wheeled on him: “I dreamed of you last night. You were much older than you are now. Fifteen, maybe twenty years. A dark-haired girl in pigtails was at your side. You were protecting her. I believe she was your daughter.—”

“My children are dead.”

Benedikt waved the comment away. “You were in a foreign land, in a wild, untamed place, lost in a blizzard.” He bit his thumb. Hermann saw that all his fingertips were bleeding. “The werewolf spoke to me, saying, ‘This is how it ends for Hermann, son of Moritz. . .’”

On the morning of February 6, 1871, the citizens of Kohlendorf woke to the news that the celebrations they had held over the weekend to mark the end of the Franco-Prussian War might have been premature. Yes, Field Marshal von Moltke had taken Paris. Yes, Minister-President von Bismarck had declared from the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles that His Majesty the Prussian King was now His Imperial Majesty the German Kaiser. But a peace treaty between the belligerent parties had yet to be signed; and isolated skirmishes were still breaking out all over the countryside.

“But the Prussian military’s successes have restored confidence in the market,” Herr Folger declared to Benedikt, Hermann, and Elischewa as they were preparing to leave. “And confidence is the grease that lubricates the wheels of commerce.” If anyone knew about the lubricative powers of grease on wheels, it was Julian G. Folger (der alte J.G.F.), the richest man in the Wuppertal and the oldest business partner of Abner and Elischewa Eltzbacher, who had made his millions vending sperm oil to all the railroad companies throughout northern Europe.

Herr Folger was a dyed-in-the-wool Benthamite and occasional Protestant. “Between confessions,” he’d mutter when pressed on his beliefs. He thought Mammon had been much maligned in scripture: “For a man can, in fact, serve two masters at the same time, by investing in profit-making enterprises that benefit his earthly ones, which is to say das Volk (the people), while simultaneously establishing charities and benefactions that glorify his Heavenly Master, which is to say du weißt schon (You-Know-Who).”

Herr Folger was a veritable Fortunatus’ purse of such wise saws. “My job is to make jobs” being perhaps his favorite. He would pause when saying it (eyes twinkling) to let its import sink in. He said it emphatically to those he had only just met and in grave and solemn whispers to those who knew him well. “Take note of what I say: My job is to make jobs.” It was a phrase he thought he’d invented; and maybe he had. No one had ever bothered to check.

When Julian’s secretary told him that “the old gal” was in town, the magnate called on Elischewa in person at the tack shop. But on learning she had come to Kohlendorf on a private matter, the millionaire’s face melted into a mask of infinite compassion, and he offered to lodge Hermann and Benedikt (“your servants”) gratis at his hotel. Then he called for pen and ink and proceeded to write out a voucher for the Trimalchian feast that they would later enjoy in his restaurant.

“I’ve always said” he remarked, placing the slip of paper in his partner’s gloved hand, “that if you treat your underlings with respect, they’ll move heaven and earth to make sure you stay propped up, even as the floor falls out from under them.” Finding the extravagant metaphor difficult to visualize, Elischewa sullenly thanked Julian for his solicitude.

On the morning of their return, they foregathered in Herr Folger’s sprawling brick stable with its wood fixtures lacquered apple-green. Hermann couldn’t help but wonder if the philanthropic tycoon who prided himself on having worked his way up from the bottom had found “the bottom” strewn with gold bars to aid him in his ascent. Realizing that such thoughts trod dangerously close to envy, Hermann crossed himself and prayed God to avert him from stumbling into that mortal sin.

When he looked up, Herr Folger was squinting at him, twirling his mustache, as if Hermann were a crack in a plaster wall that needed to be patched.

Elischewa’s melancholy eyes were dry and bloodshot. She had no more tears to shed. Her eldest brother, the proprietor of the tack shop, had come to see her off. He stood at her side, and, meeting Hermann’s gaze, nodded curtly to signify that his sister now knew the sad fate of her youngest son, Joseph, an officer without commission in the Prussian military who’d been murdered in his Berlin barracks over a decade ago, most probably at the hands of a rabid antisemite whom he had served with.

It was also Elischewa’s elder brother who had realized that morning that Wellington, the Eltzbacher’ stallion, was dying. “Equine shivers,” he had pronounced with a melancholy shake of the head. He had said this as they tried to back him up into the harness. “He’s fighting when we do this. And his muscles are twitching. I’ve seen the condition before. I’m very sorry, sister.”

It was just as the one-eyed stranger on the road had predicted, Hermann thought.

Wearing his work gloves to conceal his bloody fingertips, Benedikt stood apart from them on the hay-strewn floor, his forehead pressed against Wellington’s cheek, which was spasming. A man in nankeens held Wellington’s reins, waiting to take the horse away to the glue works outside of town.

“Elischewa,” Herr Folger said, “I insist you keep the replacement horse as long as you need it.” He made a jaunty flick of the wrist. “As you can see, I have a herd to draw upon, including a few thoroughbreds.”

“Thank you, Julian. But I’ll send the horse back once we’ve returned.” Considering the circumstances, assuming her customary mien of unruffled reserve.

“Before you dash off,” he said, removing an envelope from his plum jacket. “I’d like you to read this. I think it will set your mind at ease. As you know, I serve as Kohlendorf’s postmaster. Well, the commander of the Wuppertal 2nd Artillery Regiment, Colonel Ludwig Landecker—who happens to be in town—had his adjutant deliver this message to me yesterday afternoon. I’m sharing it with you now, even though will soon to be published in all the newspapers throughout North Rhine and Westphalia.”

He handed it to her. Frau Eltzbacher read it through. Her reaction was less ecstatic than Herr Folger had expected. She summarized it to her brother and Hermann. “The Prussian government has issued a directive to all troops returning from France that no commercial coaches or horses (in what is now being called the Restored German Reich) are to be molested or appropriated by the military. Those who violate this directive face severe consequences.”

“Does that mean we’re back in business, Frau Eltzbacher?” Hermann asked.

“So it would appear,” she said, acknowledging Herr Fogler’s broad grin with a halfhearted one.

“Anent to which,” Herr Folger added, flinging his arms apart like a carnival barker, “I’d like to send three horses back to the inn to be on standby. The north-south relays are anticipated to resume within a day or two.”

Bendikt overheard this and approached the chaise, where a fresh bay had already been put into the harness. “Since we don’t know how tame your horses are, Herr Folger, I shall lead them by the reins myself. Brother Moritz,” he said, using Hermann’s alias, “I’d like you to manage the cart carrying Frau Eltzbacher.”

The three horses were brought out and Hermann and Benedikt tied the leads through the bit rings. Elischewa embraced her brother and bade Julian farewell with a stiff nod, refusing to shake his proferred hand, prompting him to snap his fingers and say, “I always forget.”

Within an hour, the north gate of Kohlendorf was receding behind them. A ragtag platoon of Prussian soldiers marched south, breaking rank to make way for the vehicle as it approached on the snow-blanked road. Hermann glanced behind him and saw Elischewa studying the soldiers with a hard look. He felt a deep sympathy for this strong-willed woman who’d taken him and Walter in without knowing anything of their past.

“Frau Eltzbacher,” he said, “don’t you feel better now?”

“About what?” She looked offended.

What a stupid and insensitive thing to say after what she’s been through.

“I was referring to the letter. It must be reassuring to know the Eltzbacher Coach Inn won’t be taken over by the military.”

“The directive protects commercial coaches and horses. It makes no mention of private property.”

Embarrassed, Hermann glanced back at Benedikt, who was walking behind them with the three horses, lost in his own reflections. He seemed to remote, like a Bedouin leading his dromedaries across a biblical desert.

They completed the journey in silence.

In the days that followed, Elischewa sank into a depression that only Walter’s presence seemed capable of alleviating. The orphan was too young to recognize the soothing effect his move to the cottage was having on her and her husband. But then Abner had remarked on numerous occasions that “Florian” bore a striking resemblance to the way Joseph had looked at that age.

So long as Walter had been in the carriage house, Benedikt had done his utmost to suppress the anguish roiling in his heart. But once the orphan was gone, the ostler became prey to unpredictable and violent outbursts, followed by effusive and abject apologies. The hushed atmosphere in the upper quarters of the carriage house became almost funereal, so much so that Monika donned felt slippers when inside, since the creak of the floorboards alone could send Benedikt off. It was as if they’d become trapped in a fairytale castle surrounded by bushes blooming iron thorns.

As the winter nights lengthened, Hermann sat in the living room, head lowered for fear of seeing the tears coursing down his friend’s wasting cheeks. One morning, Hermann and Monika found Benedikt drunk on the rug. And so Monika held the door to their bedroom open, so Hermann could help put him to bed. It was the first time Hermann had been in this private sanctum, where two small beds stood on opposite sides of the room; and he felt his heart lurch, when he glimpsed a dejected crib in the corner that had been repurposed as a clothes hamper.

Two nights before Benedikt’s mental collapse, Monika tried to enliven the insipid hours with a humorous anecdote: “Frau Eltzbacher told me that Florian’s cat won’t leave Abner’s side, except to eat and do its business. It’s fallen in love with him.”

“It knows the old man’s dying,” Benedikt muttered. When Monika looked at him, he wiped his stubbled chin, and smiled. “Cats have an instinct for such things.” Then he glared at Hermann, resentful.

And now all was chaos, and the ostler had gone mad. “Grab the pots,” he said through clenched teeth. “Take them downstairs. I can’t carry them. My hands are shaking.”

Hermann wrapped a cloth around each handle, lifting them from the stove. “What’s happened to you, Benedikt? What is it you need to tell me?”

“The rest of the story!” he snapped, pursuing Hermann from the living room to the corridor.

What ensued was a rambling disquisition full of asides and broken clauses, repeating much of what had already been said. He spoke of his first meeting Fr. Matteo; and strangely alluded to the man’s carnal proclivities, feeling an urgent need to stress that his master never treated him in a vile or untoward fashion.

“What does this have to do with anything?!” Hermann asked, lugging both pots down the stairs, as the scalding hot water sloshed over the rims and fell on the steps.

“It has everything to do with what follows. . . . I spent two years in Fr. Matteo’s company, during which time he taught me much, telling me over and over again the full history of the demon, while bemoaning and repenting for his own role in bringing the Satan’s minion back to the valley of Mariahilf.”

When they had reached the bottom, Benedikt told Hermann to go to the tub and empty the pots into it. This done, the ostler stepped in, shaking, whether from the commingling temperatures or whatever malevolent force had its grip on the man’s soul, Hermann could not tell. The upwelling steam enwreathing Benedikt’s dour features made him look in the lantern light like the ghost of Samuel summoned by the weird woman of Endor.

“My master and I returned to Mariahilf two years after the cannibal’s burial. But the village had been reduced to a scorched ruin. My family! My home! All was gone!”

Hermann sensed that not knowing what had happened to his loved ones had tormented Benedikt in the intervening years. But he feared that, if he revealed what he had learned from Professor Wilhelm Hertz in Munich concerning the werewolf’s suspected hand in the slaughter of every man, woman, and child in village; and of how the Austrian authorities had put it to torch to conceal what they could not explain, Benedikt might, in despair, take his own life.

“Fr. Matteo did what he could to console me, but we knew we must take shelter. The only building in the valley that remained untouched by the flames was the chapel of Our Lady of Mercy on the grassy bluff. And so it was to that ancient edifice that we resorted, as the first drops of rain fell in the gathering twilight.

“The weight of the chapel’s terrifying history bore down on us both. But Fr. Matteo spoke reassuringly, saying that the light of God could never entirely be extinguished from a chapel that had been consecrated to His Holy Mother—no matter how damned the soil on which it had been raised might in bygone days have been.

“I fell asleep in my master’s arms before the Roman altar, the oldest part of the building. My unconscious mind was shot through with an array of unrealized sensations and half-formulated abstractions. I felt I had become the stonemason's son, even Melchior of Mariahilf, and that I now crouched before the altar, as he had done on that autumn night in the eighteenth century when he found the wolf-faced medallion secreted away in the hollow space of the altar.

“At dawn, my eyelashes were still damp with the tears I had shed in the night. My waking fancy imagined a connection between this and the swollen waters racing between the banks of the river Inn in the distance. ‘Sapere aude, dare to know,’ I heard Fr. Matteo whisper passionately into my ear. And then I felt him nibbling my earlobe, as he caressed my back side. A hot stickiness clung to the front of my shirt and breaches and I feared that I had been visited by the selfsame nocturnal emission Melchior had experienced on the night he discovered the medallion.

“As I opened my eyes, my vision slowly crystalized. The enormity of my wretched situation bore upon me in an instant and I froze, upraised on one elbow, as if stricken into stone. Beside me was the ripped-open torso of Fr. Matteo; and near the chancel wall lay his severed head, facing me with an expression of ineffable horror lingering in those dead eyes. But something else was in the chapel!

“My master’s head was roughly kicked aside by the taloned foot of what I thought at first to be a giant of a man. The shaggy figure leaned toward the wall, studying the Baroque mural. In the dim glimmers penetrating the vaulted chapel from the double-door, which was now flung wide open, I saw the creature in profile. I watched in awe as the gray ill-jointed fingers touched (with supreme reverence and delicacy) the face of one of the painted images.

“‘Théophile. . .’ the monster said, whimpering as it recognized the Waldensian boy whom Melchior had betrayed and murdered. The monster rose to its full height, admiring the outsized image of the Virgin Mother, beneath whose broad cape the saints and apostles knelt with heads uplifted. Clasping its hands in prayer, it spoke without a trace of mockery in its anguished voice: ‘Mary, Mother of God, release me from this curse!’

“The creature’s plea was answered by two streams of blood dropping vertically from the painted eyes of Our Lady of Mercy. Enraged, the monster’s howl shook the rafters; and, without a second thought, I sprang to my feet and ran. The werewolf’s heavy tread shattered the chapel’s stone floor, the cracks spreading from under my feet and irradiating in the direction of the open door and the precious sunlight beyond.

“I believed in my folly that the thing’s powers were limited to the dark; and that, if I could only reach the cemetery outside the double-door, I would be safe. But in my haste, I fell. When I rose again, I could not move. I felt its breath on my neck.

“‘I will not hurt you,’ it said. ‘The Devil does not slay his messengers until their commission is fulfilled. All you have learned of my story, you will pass on to the boy whose unholy birth you witnessed beneath this very roof.’ He was speaking of your birth, Hermann.—Your birth into death! ‘When you have shared with him all you know,’ the voice continued, ‘you will be released.’

“‘Meaning I shall die?’ The werewolf did not answer me. And I dared not turn around. Suddenly, my shirt was torn from my back, and I felt its claws raking my flesh near the base of my neck. The pain was unspeakable. But I could not scream. ‘It is done’ was the last thing I heard it say, as I fell insensible to the floor.

“Many days later, Fr. Matteo roused me. I told him what had happened. But as I spoke to him, the apparition vanished, and found that I still lay stripped to the waist at the chapel’s threshold. My belongings lay neatly stacked close by. The base of my neck throbbed; and a nauseating stench assailed my nostrils. I heard a buzzing that I thought was in my head. But when I turned around, I saw the putrefying remains of Fr. Matteo covered in flies lying on the shattered floor; and the sacred mural that for nearly one hundred years had graced the chancel wall was gone.”

Benedikt pulled off his nightshirt and turned his back to Hermann, revealing a raised scar at the base of his neck that resembled the face of a wolf. Reaching for a scabbard hanging near the lantern, Benedikt unsheathed a slender blade. “Remove it,” he said, reaching over his shoulder and slicing deeply into his flesh.

“My God!” Hermann cried, seizing the knife. “Stop!”

“Remove it!” the broken man repeated in tears. “If you don’t, I will be dead by dawn.”

Hermann set his jaws grimly to the task, knowing in his heart that what Benedikt was telling him was the truth. With the tip of the blade he pried open the gash already made. The ostler groaned and recited the Lord’s prayer, but refused to flinch or move, as the tub water thickened with his blood.

Hermann saw something glinting in the firelight beneath the flesh. His fingers invaded the oozy gap and made contact with a coin-sized piece of damp metal. He pulled the disc out. It was attached to a rusty chain that had become ensheathed in nerves and veins that now elastically snapped away and retracted into the aperture. It was as though the trinket had fused itslef to the Benedikt’s spinal column.

Hermann laid the knife on the crate; and, with his right hand free, reached for a towel. He was afraid as to what might happen if he dropped the object he clutched in his left fist. But before he could staunch the wound he had made, something miraculous happened. Benedikt’s skin began to heal on its own. A fresh layer closed over the lacerations and punctures. All the blood turned to water; and the gouts that had spurted onto Hermann’s own clothing were now evaporating.

Benedikt’s face was radiant as he stepped from the tub, because his madness, like Saul’s at the touch of David’s harp, had fled away. But he was ashamed, because he knew that, in shedding himself of this onerous burden, he would be forcing Hermann to take it up. He pulled his nightshirt over his head before he spoke.

“Although I feel like a man reborn,” he said, “I derive no pleasure in leaving you with this. . . keepsake.”

Hermann knew what the relic was before looking at it. It was the medallion the demon had bestowed upon his mother when she was pregnant with him. It was the medallion that Frater Melchior von Mariahilf am Inn had unearthed in the chapel of Our Lady of Mercy in the early eighteenth century.

Benedikt looked askance at it. “If you try to cast it away, it will come back to you, bringing in its train even greater sorrows.” The ostler went to the staircase, pausing on the bottom step: “It was always meant for you, Hermann, son of Moritz.”

By the time Hermann returned upstairs, the snow had begun to fall. Benedikt had already put on his work clothes and boots; and, grabbing his coat on the hook, departed. From the window, Hermann watched him cross the yard and knock on the inn’s back door. When Monika answered, he fell to his knees, sobbing. She raised him up and the two of them embraced in tears.

Elischewa was in the upper guest room directly opposite Hermann, making the bed. On hearing the disturbance, she had gone to the window to investigate. She looked up, and her suspicious eyes met Hermann’s.

He stepped behind the ragged curtain, embarrassed. The medallion felt heavy in his hand. He frowned and recited a prayer before placing the chain around his neck. Then he waited. He felt no different. But all at once, the candles in the room went out, though the low fire in the stove still crackled.

Under the cover of the darkness the room had been plunged into, he returned to the window and looked out. Benedikt and Monika had withdrawn into the coach inn. Elischewa was exiting the guest room, candlestick in hand.

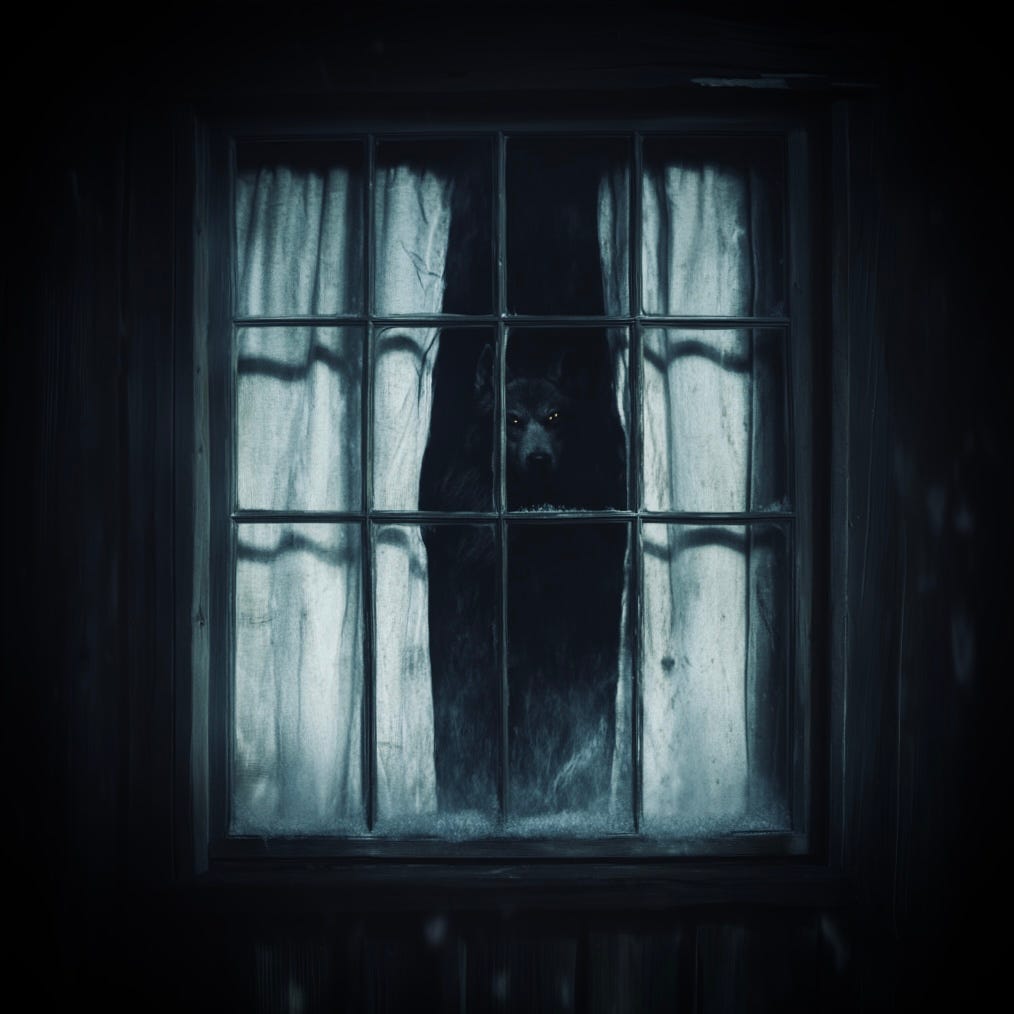

That night, Hermann dreamed a wolf-faced man had been hiding in the guest room while Elischewa was there. When she had left, the man went to the window and stared at Hermann from depths of the pitch-black room.

But Benedikt, who stood behind him in the dream, touched the base of Hermann’s neck and whispered into his ear: “That’s not the guest room. It’s the carriage house window. And the wolf-faced man peering out of it is you.”

What a tale! I can't wait to see it in book form.

Poor Wellington :-( And that surgery was unforgettable!