Upon the fertile earth Zeus has at his disposal thrice ten thousand ministering spirits, who watch over mortal men, taking note of their righteous judgements and wicked deeds as they roam, mist-clad, throughout the land.

(Hesiod Works and Days)

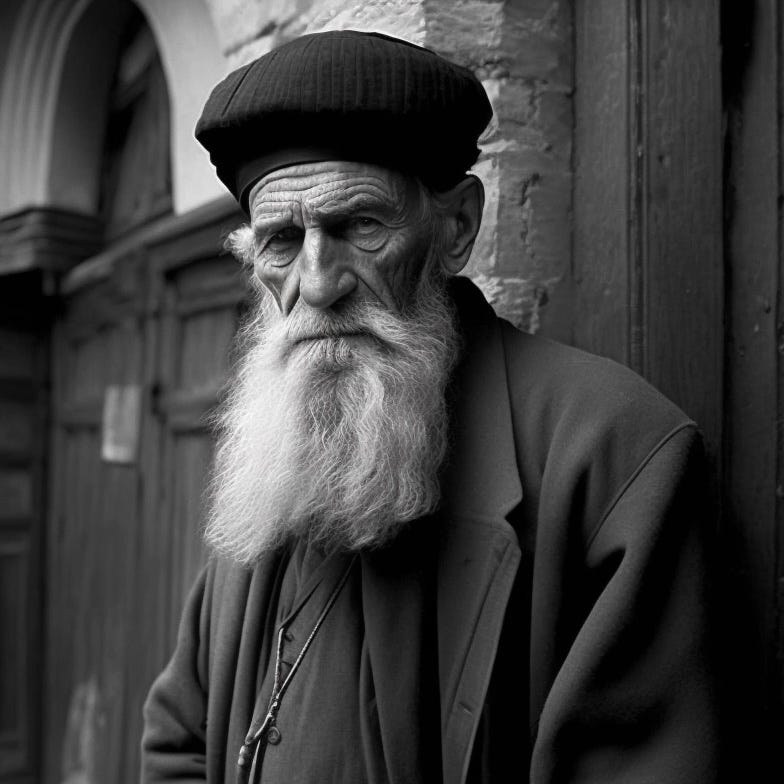

Chapter 2: Manolios

Dagitsidos celebrated its centennial on the 4th of May 1934 with no bunting and little fanfare. Standing in the town square at noon, Uncle Spiro read each citizen’s name from two crumpled sheets of paper he held in his hands. He’d waxed and curled his long mustaches for the occasion.

As each name was read, Uncle Costa struck a cowbell with a stick. When a child’s name was read, Uncle Costa struck the cowbell twice and winked at the parents. This displeased 14-year-old Markos, who told Uncle Costa that he should only have rung the cowbell once for him.

The witch came out of the mountain to participate in the ceremony. This was the first time Dorcas, the cobbler’s daughter, had laid eyes on the old hag. Dorcas had not been present when the witch arrived the day before. Manolios, the carpenter’s son, stood far away from the crowd. He looked shyly at his feet when Uncle Spiro said his name.

Since no one knew the witch’s name, Uncle Spiro simply called her “i mágissa” (the witch). The witch seemed pleased by this and repeated “i mágissa” several times, nodding proudly at the women on either side of her.

Dorcas observed the curious way the hag behaved and decided to visit the woman the following day to see if she really was a witch. The witch knew full well that Dorcas planned to bring a basket of eggs on the morrow, and ask for a fertility spell (despite already being pregnant). She knew these things because the witch’s experience of time was not as other people’s. Poor Dorcas could never have imagined as she stood in the crowd studying the witch that it was the witch who was studying her.

Uncle Spiro concluded the ceremony by saying, “And so it is with great pleasure that I announce that as of this, the 100th anniversary of the founding of Dagitsidos, our population stands at 100 souls!” Uncle Costa beat the cowbell repeatedly amid thunderous applause and general good cheer.

Only two of the town’s residents were missing: Yiayia Elena and Papa Nikolaos. It was not surprising that Yiayia Elena did not attend, since she was dying, but the absence of Papa Nikolaos was interpreted by some as a snub. Mama Irene had invited the priest, but he’d declined the invitation by walking away from her without uttering a word.

As the crowd moved to the cloth-covered table that had been set up in the middle of the town square upon which were four iron pans filled with four kinds of moussaka prepared by the principle households of Dagitsidos, no one realized that, even though the witch stood blithely in their midst, she was at that very same moment kneeling by the deathbed of Yiayia Elena, comforting the old woman whose breath had become labored as the end drew near.

“Not yet, sister,” the witch told Yiayia Elena. Then she leaned over and breathed into the old woman’s mouth. Her breath was fiery and blue-white, and it rallied the dying woman who was grateful, and sat up in bed.

Yiayia Elena and the witch chatted familiarly with each other, as if they’d known each other for years, which in a way they had. Yiayia Elena asked the witch to tear open the pillow under her head, because there was something inside of it that she wanted the witch to take away.

“But then you won’t have a pillow to lay your head upon,” the witch said quizzically.

“I don’t like pillows,” Yiayia Elena snapped back.

The witch tore open the greasy pillow, which was covered with jumping lice. In the midst of the rotting sheep-wool stuffing, she found a little doll that looked just like Yiayia Elena. It was even wearing the same black robe that the dying woman had on now.

“Part of my problem,” Yiayia Elena complained, “is that this little wicked doll has been sucking the blood out of my scalp at night. When I was a child, she too was a girl. And she wore a bright blue dress that I made for her. I sewed her up in that pillow before my first marriage, because I thought she would bring me luck. But she hasn’t. She just chews at my scalp as I sleep. She does this because she thinks that if she drinks my blood, she will regain her own youth… Please take her away and punish her.”

“Of course, sister.” The witch said, rising and taking Yiayia Elena’s doll with her as she walked out of the carpenter’s house and back up into the mountain pass. “So Dagitsodos already had 100 souls,” the witch told the little doll. She did this even as she simultaneously applauded the news in the town square that Dagitsidos had 100 souls that day. Then the witch went to the table where the moussaka was being served up and accepted the bowl that Yiayia Elena’s beloved daughter, Philippa of the Holy Vision, offered her.

Philippa had added a dash of cinnamon to an original recipe that her mother had taught her when she was a girl. Yiayia Elena had perfected the recipe, which Philippa ruined by adding the dash of cinnamon. Philippa claimed that this moussaka was a culinary marvel of her own invention that had come to her in her sleep.

The witch knew full well that Yiayia Elena’s daughter was a colossal fraud. So she took a bite of the moussaka and made a retching noise. She told Philippa of the Holy Vision, “This is garbage is a corruption of a recipe that was so much more flavorful.”

“You don’t have to eat it, you filthy beast!” Philippa snapped.

“If this is all you’re offering me, I won’t!” Then the witch cast the bowl to the ground and walked away.

May 4th, 1934 was a Friday. By the following Monday the weather had cleared. The sun set, and the landscape was bathed in the pale glow of a crescent moon.

Keeping to the shadows, Manolios crept up the trail that led into the mountain. He was unaware that Dorcas, the mother of his unborn child, had already visited the witch.

The gangling youth paused midway up the trail to make sure no one saw him. To his right were the stairs that led down to the narrow courtyard between the mountain and the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God. The doors of the church stood open. Dim light issued from within and filtered out of the windows and decorative perforations along the red-tiled barrel dome. The cross on the dome was level to where Manolios stood. Fortunately, there was no one outside. Manolios was embarrassed by what he was about to do: he was going to consult the witch.

He held a flashlight in his right hand. It belonged to his father, Loukos, who used it for work, but used it sparingly. It was the only flashlight in Dagitsidos. Loukos warned Manolios not to overtax it because the wires might burn up or the lens crack from the heat. Manolios made it into the mountain’s canyon and walked carefully in the dark until he stood well away from the entrance. He didn’t want anyone in the town below to see the light. When he was near the enclosure, he turned on the flashlight. The bulb popped and went out.

“Fuck!” he yelled.

His voice carried through the night air all the way down to the town of Dagitsidos, where it entered the house of the melancholy cobbler, the father of Dorcas. The girl grinned in her sleep and touched her swollen tummy. She was dreaming that Manolios was building their bed and had accidentally hit his thumb with a hammer. He yelled “Fuck!” in her dream, so she went to him and kissed the wound. Then she kissed him full on the lips and caressed the cleft lip with her fingertips, as the baby cried in its crib, but not as loudly as it was crying now in her womb, or so it seemed in the dream.

Manolios entered the enclosure and was surprised that the moon’s beams made it bright and luminous. He heard the fluttering of doves’ wings. They made cooing noises to alert the witch that he was there. But the witch didn’t need them to tell her that. She stood at his side and caressed his cleft lip with her fingertips as Dorcas had done in her dream. Manolios gasped and sprang away but didn’t cry out.

“You’re brave,” the witch said. She pointed to her own lip and said, “They make fun of you for that, don’t they?”

He didn’t respond. He rested the broken flashlight on a rock.

“Could you help me build a pergola?” the witch asked in a weedling voice.

Manolios didn’t know what she was talking about. She gestured to the middle of the enclosure. In the moonlight he saw six 14-foot poles resting in sockets. They stood 10 feet from one another. Seven more poles of the same size rested against the wall of the enclosure.

“I’m an old woman,” the witch said. “I can’t build a pergola by myself.”

Manolios had no idea where the old woman had found thirteen poles, nor how she’d managed to dig sockets into the stony ground and erect six of them by herself. But he found it ingenious. He was a bit awed by the woman, and she was treating him kindly, almost as kindly as his grandmother, Yiayia Elena, did. The witch had also expressed an immediate sympathy for his disfigurement. Manolios suspected the witch was not a bad person. He had intuited this within moments of meeting her.

Ignoring what she had said about the pergola, Manolios blurted out: “My grandmother’s dying. I want her to get better. She doesn’t make fun of me because of this.”—He pointed at his cleft lip and scowled. “She can’t die.”

“We all die,” the witch said.

The witch didn’t mention her visit to Yiayia Elena three days prior. The reason she didn’t say anything about this was that the moment she walked out of the carpenter’s house that day, Yiayia Elena’s pillow sewed itself back up and repositioned itself under the head of the old woman; but Yiayia Elena then slipped into a deep coma. The witch feared Manolios might blame her for his grandmother’s comatose state.

Manolios looked at the witch curiously. “So then my grandmother won’t recover?”

“I didn’t say she wouldn’t recover. I said we all die. If that makes you sad, I don’t know what to tell you.—But if you close your eyes and think about the place where you cherish your fondest memories of her, well… that’s where she’ll be, even after she’s passed away.”

Manolios thought about this. The answer came to him in a flash. Yiayia Elena’s kitchen was where he cherished his fondest memories of her. When the other boys had bloodied his nose that day and told him he looked like a freak, he ran home and into the kitchen, and he curled up under the table, crying. Yiayia Elena crawled under the table with him. She stroked his hair and told him that he was not a freak, that he was special, and that he would do something so remarkable someday “that your children will honor you, even to the tenth generation.”

Yiayia Elena always gave Manolios the choicest cut of meat when she ladeled out the bowl of stifado for him. And when Manolios had been apprenticed to his father, and would return sweating and fatigued from the workshop, Yiayia Elena would remove a grilled chicken liver from the pan with a double-tined fork and serve it to him on the sly, holding one finger over her lips to let him know that this was their little secret. With gratitude and love, Manolios had built a cupboard for his grandmother, so that she could store her utensils and crockery. This brought tears to Yiayia Elena’s eyes. And now Manolios wept as he remembered it.

The witch saw in the pale light of the moon that the boy was weeping. She tried to cheer him up by speaking of mundane things. “These seven poles resting against the rock must be lashed to the top of those six poles. They will fortify the pergola… Then I can cover it with branches, maybe cloth, I don’t know.”

Manolios went to the middle of the enclosure and inspected each of the six poles.

The witch asked slyly, “Will you build me a pergola, Manolios the carpenter’s son?”

He looked at her in astonishment. The whites of her eyes seemed to glow in the moonlight. She must be a witch, he thought. She knew my name and profession. But she was also at the centennial celebration, so maybe someone told her I was Manolios, the harelip son of the carpenter Loukos.

Manolios looked at the pergola again. “Yes,” he said. “I can build you a pergola. I can even cover it with wooden slats. I’ll need to fetch rope and other equipment. And I may need another person, besides you, to help me. There’s a girl who’s pregnant, but she’s strong. I won’t let her overtax herself.”

“Of course you won’t,” the witch said with a grin. “I knew you could construct a simple pergola. You’re an artificer, like the god Hephaestus.”

“Didn’t he make a shield for Achilles?” Manolios asked.

“Very good. You’re quite clever!” the witch said. “Yes, he was a forger, but he was also a builder, like you. Do you know what the god Hephaestus would do once he’d completed a magnificent temple dedicated to his beloved mother, Hera?”

“No,” Manolios said.

“When Hephaestus was done, he would take his hammer and chisel and make a crack in one of the temple’s marble columns. Do you know why he did that?”

“No,” the boy said.

The witch brushed her fingers tenderly against the young man’s cleft lip. This time Manolios didn’t shy away.

“He did this because otherwise the temple would be perfect. And perfection is vouchsafed only to the gods.”

Manolios smiled. “I will return tomorrow and build the pergola!” As he said this, the broken flashlight came on. He gasped in wonder at this proof of the witch’s supernatural abilities. He grabbed the flashlight and sprinted as fast as he could from the mountain pass. He felt refreshed. He was no longer embarrassed by what he’d done, nor ashamed to have befriended the witch.

The witch went to one of the many streams trickling down the rocks. She slaked her thirst, drinking from the palm of her hand. Some of the doves flew down and drank with her.

As Manolios descended the hill, he kept the flashlight on and whistled like a nightingale. He stopped on the trail above the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God and whistled again the nightingale’s song.

Papa Nikolaos stood outside of the doors of the church. He looked up at Manolios. The boy shined his flashlight in the priest’s eyes and laughed. Papa Nikolaos clucked his tongue and mumbled something in disgust. Then he went back inside and slammed the doors shut.

The following day, Uncle Costa the fierce-eyed swineherd walked up toward the mountain but stopped at the steps the led down to the church. He had been summoned by Papa Nikolaos. He wondered if he was in trouble. With a sigh, he descended the steps.

Uncle Costa could not recall doing anything scandalous for at least half a decade, so he couldn’t figure out why the priest needed to talk to him. He said to himself: “Papa Nikolaos is looking thin these days. He probably wants a suckling pig for free. Well, that’s not going to happen—not unless he’s discovered something about my past that requires extra prayers to fix.”

Papa Nikolaos was outside, feeding a scrawny goat tethered to a stake. As Uncle Costa reached the last step, Papa Nikolaos gestured to the front of the church and went back to feeding the goat.

Uncle Costa walked across the courtyard. His eyes fell on the gate over the steps leading down to the cemetery. He pushed away the memory of that horrible morning forty years ago. He could still hear the screams of the fiery young beauty, Elena. For when she was young, Yiayia Elena was known throughout Epirus as Elena the sloe-eyed.

The scream of a pig dying under the knife is horrible enough, but nothing Uncle Costa had ever heard in his life had compared to the howls that issued that morning from the lips of sloe-eyed Elena in her grief.

Uncle Costa walked to the low wall that formed a barrier between the courtyard and the cemetery. Crooked flagstones formed the staircase that descended between the graves and tombs. At the bottom of the steps was the river Acheron. In former times, a walkway ran along the base of the cemetery, hugging the mountain at the river’s edge. But at some point, well before Uncle Costa’s time, the walkway had sunk into the river. One could still walk on it—water up to one’s waist—but there were tales of skeletal hands grasping ankles, and the general consensus that stepping on the walkway if one’s soul was burdened by a heavy sin could be fatal.

The sunken walkway ended at the mouth of the cave leading up to the enclosure where the witch had taken up residence. In pre-Christian times, the mouth of the cave had been a chapel where cadavers were washed prior to burial, a custom that continued well into Byzantine times. During the Turkish interlude, the cave was abandoned. But when Dagitsidos was founded, the cadaver-washings resumed—until that day forty years ago, when sloe-eyed Elena gave birth to her beloved daughter, Philippa of the Holy Vision, in the black waters of the Acheron beside the corpse of her fifth husband, Mihalis whom she loved.

There were ancient frescos of shrouded figures lining the walls of the cave chapel. At some point in the Middle Ages, iconoclasts had chiseled away the eyes and mouths of the frescos.

Uncle Costa woke from his reverie. Papa Nikolaos was snapping his fingers and hissing. The priest pointed to the entrance of the church. But both men shared a look of mutual apprehension, for the weather was misty and humid as it had been that morning long ago when they were both young.

Uncle Costa walked inside the church. Uncle Sprio was already there.

When Uncle Sprio saw the men enter, he started praying as if he’d been praying before they’d appeared. The narthex of the church was heavy with the pong of incense. Hundreds of candles were ablaze in the sand-filled metal troughs.

Uncle Costa walked behind Uncle Spiro, and stood on Uncle Spiro’s right side to show he was not subservient to him.

Papa Nikolaos walked to the iconostasis and mouthed a silent prayer. Then he turned and glowered at the ceiling, as if searching for words.

“It has come to my attention,” the priest said, “that there is a witch living in Dagitsidos. A witch who claims to be able to tell the future, read fortunes, who communes with familiar spirits—a witch who aims to establish a taverna in the mountain pass?!”

Uncle Costa and Uncle Spiro glanced at each other nervously.

Papa Nikolaos clapped his hands together and said, “This is exactly the kind of charlatan this town needs to attract tourists.”

“He’s right!” Uncle Spiro shouted, relieved that Papa Nikolaos was not angry with him. “If word gets out that there is a witch in Dagitsidos, people like the ones who write newspapers and magazines, will come here to spread the word!”

“Journalists,” Uncle Costa interjected.

“What?” Uncle Spiro asked.

“They’re called ‘journalists’.”

“I know they’re called journalists!—You always interrupt me!” Then he turned to Papa Nikolaos and shouted, “He always interrupts me when I try to make a point!” Then he lashed out again at Uncle Costa: “You forget, Mr Pig Farmer Constantine, that I can read, unlike you! You’re nothing but a stupid oinking pig yourself!” Here Uncle Spiro made a gesture as if he were wiping filth from his hands. “Your grandfather was my grandfather’s servant.”

Uncle Costa wheeled on him and said, “And your grandmother was my grandfather’s whore!”

“Enough!” Papa Nikolaos shouted.

The two men crossed themselves, and Uncle Costa shrugged apologetically at an icon of the Virgin Mother that hung next to him.

“Then we are agreed!” Papa Nikolaos said. “We will provide the witch with the necessary facilities to establish her taverna in the mountain pass.”

Uncle Spiro and Uncle Costa nodded in unison and the meeting of the elders was adjourned.

Once Uncle Spiro and Uncle Costa had left, Papa Nikolaos paced back and forth in the narthex. He plotted how he might use the witch’s presence in Dagitsidos to his own advantage. It would only take a few weeks for his beautifully written sermons on the evils of witchcraft to make their way to the printing house of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Mount Athos in Salonica. Once these sermons were published and circulated throughout Hellas, Papa Nikolaos would be able to apply for a transfer to one of the several monasteries on the slopes of Mount Athos to live out the rest of his life, far removed from the unwashed rabble of this godforsaken town he had been sent to nearly half a century ago.

While the elders met in the church that day, Dorcas held a wooden ladder steady for Manolios, who was hard at work lashing the wooden poles together to make the pergola for the witch. The witch made no mention of having spoken with Dorcas a few days prior, because she knew the girl did not want her beloved to know about the visit.

Working patiently and expertly, Manolios had Dorcas hand him each of the seven poles leaning against the rocks. The tips of all the poles were pointy. The boy lashed these seven poles to the six in the foot-deep sockets. The vertical poles were so tall that they protruded 4 feet over the horizontal poles forming the pergola’s roof. When Manolios had finished, he and Dorcas worked together to collapse the ladder.

“I found some spare wood in my father’s workshop,” he told the witch. “I’ll be able to use them as a cover, but I’ll have to bring them another time.”

“It’s spectacular!” The witch clapped her hands. “You’ve done a wonderful job!”

Manolios smiled at Dorcas, who blushed.

Suddenly, the mountain pass echoed with the sound of a young boy’s cries. Into the enclosure rushed 14-year-old Markos. He stopped, panted, and leaned forward with his palms on his knees. Then he shouted, “Manolios! You must go home! Something’s happened!”

Mama Irene had already alerted the barber and baker that a miracle had taken place at the house of Loukos the carpenter. The men and women of Dagitsidos made their way to the carpenter’s home. Manolios ran ahead. His mother stood at the threshold and when he tried to enter his own house, she hissed and warned him to stay put.

Little Markos had remained behind with pregnant Dorcas, who walked barefoot down the trail and cut across the jagged slope to shorten the trip. She needed to see what the commotion was about.

When the townsfolk were assembled before the carpenter’s house, formerly the house of the Turkish Governor, Philippa stood aside. Red-eyed and frail, Yiayia Elena appeared at the front door in her black hooded robe.

“Rejoice,” Philippa of the Holy Vision said in a hollow voice, “for the Lord has restored our dear mother’s health.” Philippa’s face was pale, and the corners of her mouth were tight with chagrin, because she hated her mother whom she suspected of murdering her father, Mihalis.

Manolios rushed from the crowd and fell to his knees, kissing his grandmother’s feet. Then he kissed the edge of her robe as the townsfolk applauded and praised God. But Dorcas turned away and wept.

“I’m actually dead,” Yiayia Elena told the crowd. They went silent. Agatha removed her pipe. Mama Irene crossed herself. But Manolios rose up and said, “No you’re not, grandma… You’re very much alive!”

The witch was not present. She stood at the mouth of the cave looking up at the bronze fragments tied to the oak tree, which clanged harshly as the wind drove them against one another. “Not yet, sister,” the witch said—and Yiayia Elena nodded when she heard this.

“I have one task left to me in this world,” Yiayia Elena said, harshly.

“Don’t talk that way, grandma,” Manolios said. “I can’t go on without you! You’re the only person in Dagitsidos that I love. Then Dorcas fled away in anguish.

The menfolk pointed at Manolios and laughed, because he had a cleft lip and cried like a girl.

Once the novelty of the miracle had worn off, the townsfolk went back to their day’s labor.

Yiayia Elena had not entirely lied when she had said “I’m actually dead,” but she’d not entirely told the truth. Anyone who had bothered to study her closely, other than Manolios, who was blinded by his love for her, would have noticed some strange peculiarities. Yiayia Elena no longer cast a shadow on the floor, nor was her reflection visible in a mirror. She didn’t seem to draw breath yet she could speak. Her heart did not beat, but she was full of blood, too much blood, in fact.

That afternoon, Yiayia Elena fried a chicken liver in her cast iron skillet and gave it to Manolios, placing her index finger over her lips to let him know that the gift was their secret. The boy was so happy. He chewed it and stood in his grandmother’s kitchen, smiling in gratitude.

Manolios did not want to fall asleep that night. He was so overjoyed that his grandmother had been brought back from the brink of death, but the excitement of the day had worn him out. He curled up on the coarse mat beside his grandmother’s bed.

When Yiayia Elena heard the boy’s steady breathing, she rose from the bed and walked out of the house. She walked across the way to Uncle Spiro’s walled plantation, the gate of which was open. She entered the mansion and ascended the staircase but her footfalls made no sound on the steps.

She opened the door and entered Uncle Spiro’s bedroom, where she found him snoring loudly, his mustachios tied behind his ears. Over his bed hung an oval portrait of his heroic ancestor, Odysseus Androutsos. Dangling from the hook on the door, was a gem-encrusted yataghan. Yiayia Elena drew the yataghan from its scabbard. She pointed the tip at Uncle Spiro, but slaying him was not her objective.

With the curved blade in hand, Yiayia Elena moved swiftly through the night, growling like a cat. She left Uncle Spiro’s mansion and made her way at a preternaturally swift pace to the trail that led up to the mountain pass. She stopped at the steps leading down to the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God. With one leap she landed on the courtyard below. From his hovel beside the church, Papa Nikolaos saw the black-shrouded figure seemingly float over the flagstones as she entered the terraced cemetery and descended its steps.

When Yiayia Elena reached a point midway down the steps, she paused and shed an undead tear. For she stood by the grave of her fifth and final husband, Mihalis whom she’d loved. Yiayia Elena continued down the steps to the river Acheron. She stepped into the water and her feet rested on the sunken walkway. Skeletal hands grasped at her ankles as she made her way to the mouth of the cave that led up to the enclosure. She heard the witch whistling in the night. When Yiayia Elena reached the waist-high water where she’d given birth to Philippa of the Holy Vision, she knew that her journey was over.

In his nightshirt Papa Nikolaos started down the cemetery steps with a candle in his hand, but froze in horror, because the air was rent by the same scream he’d heard forty years ago.

Yiayia Elena had drew the blade of Uncle Spiro’s yataghan across her ice-cold throat, and a fan of black blood spurted from the wound and dimpled the surface of the river of death. She howled in the night, even after her vocal cords were cut. And the witch in the mountain pass sang an ancient lullaby that Yiayia Elena had taught her long ago.

“She’s gone!” Manolios cried over and over again, sprinting up to the mountain the following day after Yiayia Elena’s burial. “My grandmother is gone!”

He rounded the corner that led into the enclosure and collapsed in front of the witch who stood at the cave’s entrance looking down at him.

“Get up!” she said. “Why are you upset? I told you we all die.”

“I can’t go on without her!” Then he smacked his own ears and wiped tears from his eyes.

“Don’t you remember what I told you when we first met? Think of the place where you cherish your fondest memories of her. And that’s where she’ll be, even after she’s passed away.”

“The kitchen?” Manolios asked in despair.

“No, Manolios,” the witch said and touched his heart.

Two nights later, Manolios, Loukos, and Philippa of the Holy Vision were awakened by a sudden crash in the kitchen. Yiayia Elena’s kneading trough had fallen from the cupboard Manolios had built for her. And Manolios was comforted, because this proved the witch’s words to be true.

Dorcas and Manolios were married in the Church of the Dormition the following week. Dorcas wore her mother’s wedding veil. The two lovebirds emerged from the church into the bright summer day. Now that Manolios was a married man and a soon-to-be father, the menfolk looked at him differently. They said that some of Yiaiya Elena’s brassiness had been passed down to him. And they felt ashamed when they considered how often they’d mocked the son of their local saint, Philippa of the Holy Vision.

The witch was barred from participating in the wedding ceremony, but she sat on the low wall at the top of the steps that led down to the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God.

“Aren’t you proud of your grandson, sister?” she asked. “You did a fine job raising him.” The witch spoke to the little doll in her hand, which had reverted from the form of an ugly crone in a black robe to that of a beautiful little girl.

“Sister, you told me to punish this doll. But I think there’s been enough punishing of the innocent in this town, don’t you?” The witch rose from her seat and made her way up the trail that led into the mountain pass. “We’re almost ready,” she said with a leer, “to start punishing the guilty.”

Continue to Chapter 3.

Thank you, Winston. I love reading about Greek and Balkan folklore. There are a lot of great resources out there for it.

Well, you kept me up for another chapter, congratulations! Hopefully, sleep will be nightmare free...