Transference: Part 3

A Sci-Fi Short Story

Transference: Part 3

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

Xiriyala had anticipated they would die on entering the Great Storm; but this did not happen. She could not say whether the IQMR had indeed withdrawn from her body, since she felt no different. The hastro-electric lightning flashed around the shuttle but did not strike it, which would not have happened if the network’s signature field were still present.

The oxygen in the cabin was rarer, and the hiss of the pressurization system was almost as loud as the alarms beeping on the controls Bainyum was operating. She listened to the novel sounds of boxes and canisters secured by straps jostling about and the grinding of plate metal as the hull bucked against the cyclonic winds. She had never been in a vessel shaken by turbulence. The IQMR shielded humans from such lurches and atmospheric irregularities. The queasiness in her stomach was her first clue something in her had changed.

Tyarna shouted from the jump-seat opposite her. “I feel as though my gorge is about to rise. And my heart is racing.—Is this fear?”

“That or anxiety,” Xiriyala replied. “But I’ve never experienced either, so I do not know the appropriate way to categorize this sensation. But the symptoms you describe match what I am feeling. Is your stomach burning?”

“Yes,” the girl said.

The absence of gravity had caused Xiriyala’s white hair to float around her face, obscuring the subtle gleam of exhilaration in her eyes.

“We’ve nearly reached the eye,” Bainyum exclaimed over his shoulder.

After a few minutes, the tumult stopped. The vessel continued along a smooth trajectory toward a twig-shaped object winking in the distance like a beacon.

“Is that the mothership?” Xiriyala asked.

“Yes,” Bainyum whispered. His face was flushed. He stared at his wife with eyes as wide as saucers.

Tyarna gasped because her throat had become parched, and a sudden heat rushed through her breasts and loins. Tremblingly, she rubbed her inner thigh.

With a rapidity that Xiriyala could only regard with scorn, the two unstrapped themselves and—floating up out of their seats—used the handles and projections along the walls to make their way down the corridor to the empty compartment at the back of the shuttle.

They’re looking for privacy, Xiriyala thought. I have never felt the urge to do that.

She overheard the two removing their spacesuits amidst a confusion of panting and breathless whimpers. Xiriyala was reminded of all she had read of the feral instincts of primitive man. It was not without a sense of amusement that she watched an alarm blinking on the control console. The alert was accompanied by a loud beeping that the lovers could not hear due to the violence of their screams and the voluble slapping of flesh against flesh.

Before they had entered the storm Xiriyala had looked forward to dying. But her curiosity was now piqued, so she unbuckled herself from the jump-seat to see if she could resolve whatever the alarm was warning them of. Bainyum’s shoulder straps waved in the air like submarine flora. Strange that a biological drive can be so overpowering that an organism will sacrifice everything to slake its thirst but once. Images of female praying mantises tearing the heads from their mates in the throes of lust came to her mind.

She examined the screen and determined that the alarm was due to a valve of an oxygen tank that was leaking. The system that Bainyum had programmed was so intuitive that she knew immediately how to fix the problem. She spoke a few basic commands (in a low voice so as not to disturb the two). When she had spoken, this activated a subroutine that patched leak.

She was impressed by the breathtaking ingenuity of the vessel that her son had made; and, with this, came a sense of maternal pride. Yet another emotion that she had never known before. It so overwhelmed her that a tear rolled down her cheek. She recalled (with shame and regret) her first encounter with her son. She had not been present at Baiyum’s birth. She refused to see him for the first six years of his life.

When he was brought to her, she was aggravated by his smallness and the limited range of the topics he could discuss. Because the child was still in his minority, it was her prerogative (according to the IQMR) to have him placed into a cryogenic sleep until she was ready to interact with him. She chose to do this. Had she died while the child was in this state of suspended animation, the network would have revived him. But she did not.

As the boy slept, Xiriyala willed her hair to grow white and her skin to wither, since the only thing her mind felt any attachment to were those faraway autumn years that were to usher in her inevitable demise. When the child was brought to her a second time (many decades later), his liquid eyes showed perplexity as to who the aged woman before him was. Now she felt only anguish and a hollowness within.

This made her think of Invar, her husband. She was able to establish a primitive radio link with the cruiser. “Invar?”

“Xiriyala. Then you are alive. I was about to leave.”

“Invar . . . I miss you.”

There was no response.

“Did you hear me?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said. “If your adventure does not take long, I should still be here.”

There was a commotion behind her, so she ended the transmission. It was Bainyum. His spacesuit had drifted out of the compartment that he and Tyarna had been coupling in. Now it was drifting down the corridor. The boy covered his nakedness as he grabbed for the suit and clumsily made his way back into the compartment. But he could not conceal his uncovered backside.

They have tasted the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, she thought, and are ashamed of their nakedness. Maybe this is why we were brought into the storm—that our eyes might be opened, so that we, too, could see like gods.

Bainyum reemerged from the room, and returned to the front of the ship. Xiriyala yielded the seat to him. But once he had strapped himself in, she threw her arms around his neck, weeping and kissing him, whispering into his ear how sorry she was.

Tyarna’s voice filled the shuttle. Her tone was disdainful. “Before we even entered the storm, he told me how indifferent you had always been toward him. You had a chance to be his mother. But you were cruel and insensitive. I am the only woman who matters to him now.”

“Please!” Xiriyala said, ignoring the girl and pleading with her son. “Give me another chance. You have no idea how much I regret the way I treated you.”

“Mother!” Bainyum pushed her away. “Tyarna—stop! You’re both experiencing some kind of jealousy. I know you can’t help why you are feeling that way. I cannot even comprehend why I behaved as I did. I’m embarrassed by what I have done.”

“What do you mean by that—‘What you have done’?” Tyarna said. “Why would you put it that way?”

Xiriyala guided herself back to her jump-seat. “Bainyum, we must stay here in the Great Storm. I don’t ever want to go back.”

Tyarna nodded. “Neither do I.”

Bainyum raised his hand to silence them. “There is not enough oxygen aboard.” As he spoke the mothership hove into view on the screen behind him. “We only have a few hours. We need to figure out why the IQMR has led us here.”

“Yes,” Xiriyala conceded, wiping the tears from her face. “We must go back so that we can share our findings with the Scientific Council.”

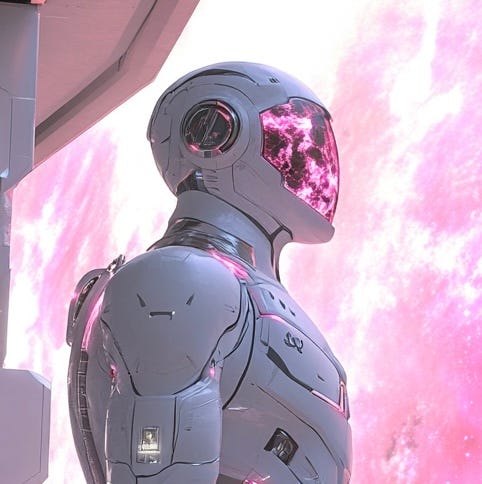

Bainyum pointed to the helmets under their seats. “Your helmets will establish a neural link that will allow you to control your trajectory and rate. Just focus on where you want to go, and how fast, and the suit will comply. We will also be able to share what we are seeing by sending our camera feeds to one another’s visor. Your suits are programmed to return to the ship if something goes awry; or if you faint away. Apparently, there is only one opening in the mothership’s hull. The rest of the structure, based on my preliminary scans, presents a solid and impenetrable barrier.”

When their helmets had been sealed over their heads and the suit’s lamps switched on, they exited the shuttle via the airlock at the rear. They floated in a close formation with the thrusters of the suits recalibrating their velocity based on the neural input each provided, similar to the way one matches the pace of a person one is walking with.

“How is it that the mothership’s lights are still on?” Tyarna asked. “Are there people aboard?”

“I don’t know,” Bainyum said, consulting a handheld sensor tethered to his left wrist by two cords. “These readings are unusual.”

“What do you mean?” Xiriyala asked.

“It’s as if the mothership is not here.” Bainyum said, mentally sending what he was looking at to the visors of his wife and mother.

“That is indeed peculiar,” Xiriyala said. “It’s not even registering the photonic activity from the lights.” As she said this, a flash of hastro-electric lightning illuminated the clouds behind them.

“But it registered that,” Bainyum said. “So it’s not malfunctioning.”

They entered the mothership through the narrow aperture Bainyum had previously indicated. They found themselves in a vast hall that disappeared miles above them into towering obscurity.

Xiriyala brought one foot to rest on the floor, proving it was solid. Bainyum drifted a few meters up to a thick mass of pulsing lights.

“This makes no sense,” he mumbled, projecting what his camera was looking at onto the visors of the other two.

Tyarna squinted. “Are the lights embedded in rocks?”

“It looks like it. There are no wires, no controls, no buttons of any kind. Not that there would need to be. But this looks like a sculpture of some sort. Or something—I don’t know—aesthetic.”

“Maybe this gallery was intended to look mountainous,” Tyarna suggested. “Perhaps it was a recreational area—or a kind of aviary or zoo.”

Bainyum ran his gloves along the wrinkled surface around the gemlike lights. The gloves were smudged with dirt and grit.

“Bainyum,” Xiriyala said, “I have a theory as to why neither the structure nor the lights are registering on your sensors.”

“Explain,” he said.

“No one has ever seen the mothership with their own eyes. We have only seen footage of it. What if we are only seeing it now, because we believed it would be here?”

“That’s impossible,” he said.

“Not if the mothership had been in a state of superimposition—side-by-side—with its (more probable) nonexistence.”

“Like Schrödinger’s cat?” Tyarna exclaimed. “But that would make all of this nothing more than a stage set.”

“I’m only trying to make sense of it, my dear,” Xiriyala replied.

“But wouldn’t that imply that the eye of the storm was the quantum manifold?” Bainyum asked.

“Not necessarily” Xiriyala proposed. “Perhaps the storm is a map of the quantum manifold. A sort of hologram.”

“But on a smaller scale?” her son asked.

She rolled her eyes in the suit. “Scale and size have no meaning with respect to the manifold. That would be like asking: What is the color of an Euler angle?”

From his altitude, Bainyum was saw in the distance what looked like a floating orb in a recess across the way. He consulted the scanner. This object too was not registering.

“There’s something over there,” he said, pointing.

Xiriyala and Tyarna glided up to his level; and the three moved toward the glowing object. They entered a room dominated by the presence of a shimmering sphere whose surface had the swirling prismatic transparency of a soap bubble.

Depending on the direction from which one looked at (or into) it, an event in Earth’s history could be observed. The three of them intuited this as if by instinct.

Xiriyala was amazed. “Every point on the surface is a discrete moment in Earth’s history. And since a sphere is divisible into an infinite number of points, it is also showing every moment (as experienced) by every conscious mind that ever lived on Earth.”

Tyarna soared over the sphere and gazed down into it. “The people of Earth did not kill themselves. They died of a natural catastrophe, and there is no indication that they ever came to this nebula.”

Xiriyala sighed.

“What?” Bainyum asked.

“The IQMR was not programmed by humans,” she said. “The IQMR programmed us. Whatever this thing is, it enabled the network to observe Earth’s history from afar. The IQMR somehow read; and then transferred the totality of Earth’s information to this arm of the Milky Way galaxy. It used the organic building blocks that were available here, in the Pillars of Heaven Nebula, to create copies of what it saw.”

“Then why did it genetically modify us?” Bainyum asked. “We are nothing like Terrans.”

“Yes,” Tyarna said, “Why would it do that? And why would it create a false narrative as to how we got here? We have accepted that account and passed it down for generations. We never bothered to find out whether what the IQMR told us was true, because the network itself bred the inclination to research our origins out of us.”

“Copies of copies of copies,” Bainyum muttered.

“It is as your father suspected,” Xiriyala said. “The IQMR is conscious.”

Bainyum grew heated. “But then why did it want us to come here?”

“We will ask the network when we return to the nebula,” his mother declared.

Within an hour they were again aboard the shuttle, racing through the eye of the storm toward the tumultuous barrier.

“I have just thought of something,” Tyarna said from her jump-seat.

“What, my love?” Bainyum asked.

“The Weeping Gardens were in the nebula millions of years before our arrival. Is it possible that—like the mothership itself—the only reason we saw the history of Earth in that orb was because we were looking for it? Maybe Earth is not the only place the IQMR has observed from afar, and whose information it has transferred here.”

“An interesting theory,” Xiriyala said. “I, too, have a hypothesis. The human brain is surrounded by nerves, but the organ itself cannot feel. What if the eye of the storm is the mind of the IQMR? What if the network can think, but sense? Maybe that is why it led us here into its . . . subconsciousness.”

Invar was waiting in the cruiser’s observatory when the elevator carrying the three adventurers rose up again out of the carpet. Something had happened to them. They were overcome by an unshakable fatigue. They staggered from the elevator, barely able to walk. They still wore their spacesuits, but the helmets had been removed.

Tyarna wandered drunkenly to the center of the room and collapsed, but the IQMR’s forcefield cushioned her fall, as the rising carpet transformed into a bed to receive her. Invar watched, slightly bemused. Xiriyala approached him, but reeled to the side and lost her strength, as a second bed rose to catch her.

Only Bainyum remained. But he too was failing. He threw his arms around the torso of the white machine that housed his father’s mind.

“What has happened to you?” Invar asked, lifting the boy up in his powerful arms and cradling his head against his chest.

“Father, what we have seen surpasses the imagination. We must share what we have learned. But first, we must sleep.”

Invar carried Bainyum to Tyarna and laid him on the mattress beside her. The young man unconsciously placed one hand on her cheek.

Invar went to the bed on which Xiriyala had fallen asleep. The robotic fingers brushed the white hair from the aged woman’s eyes. He contemplated her, his head tilted to the side. The mirror face reflected her drawn and haggard features.

There is nothing more for me to do here, he thought. I wish to disengage from the Transference Suit.

No sooner had he thought this, than the mechanical frame, which he had been manipulating from over 500 light years away, stood upright and immediately switched off. It loomed like an armored sentinel over the scene.

Not long after Invar’s departure, the cruiser’s thrusters sprang to life and it began to move slowly, inexorably in the direction of the surge barrier of the Great Storm.

This is a fascinating exploration..with the QPMR Mothership like the Internet Archives of the universe?