Flash Fiction Was All the Rage Among Writers of the Vienna Secession

Short-form fiction is not new but the names we call it by today are: flash fiction, microfiction, sudden fiction, dribbles, drabbles, etc. This essay focuses on the popularity of “very, very short stories” during the Vienna Secession. The tales surveyed range in length from two sentences to two pages. To understand how the authors of the time perceived these stories, we will need to anatomize the German word Märchen, commonly and misleadingly translated as “fairy tale(s).”

Most German-speaking fin-de-siècle authors would likely have been mystified by the contemporary obsession with pigeonholing such tales into categories based exclusively on the number of words they contain. This essay concludes by revisiting these recent coinages and questioning their utility.

The Vienna Secession takes its name from a group of Austrian artists, the most prominent of whom was Gustav Klimt (1862–1918), who seceded in 1897 from the Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs (Austrian Artists’ Union), headquartered in Vienna’s Künstlerhaus. They were protesting what they perceived to be overly restrictive rules the Union’s authorities were imposing on them about what was and was not acceptable to represent in the plastic and applied arts produced in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The movement is generally said to have ended around 1918, which was not only the year Klimt died, but the year the Empire itself came to an end. The movement is related to and an extension of the Art Nouveau and Jugendstil (Youth Style) movements.

Peter Altenberg (1859–1919)

The walrus-mustached flâneur, Peter Altenberg, is so revered in Vienna that a life-size mannequin of him has greeted visitors to the First District’s Café Central since 1986.

In the years leading up to the 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the Café Central was a hotbed of political intrigue and revolutionary activity — frequented by the likes of Russian chess-playing expat, Leon Trotsky, Croatian mechanic, Josip Broz (later Marshal Tito of Yugoslavia), antisemitic mayor of Vienna, Karl Lueger, and equally antisemitic artiste manqué, Adolf Hitler. The café was destroyed in World War II, and the reconstructed confection that now occupies the southern end of the Palais Ferstel is meters away from where its famous namesake once stood.

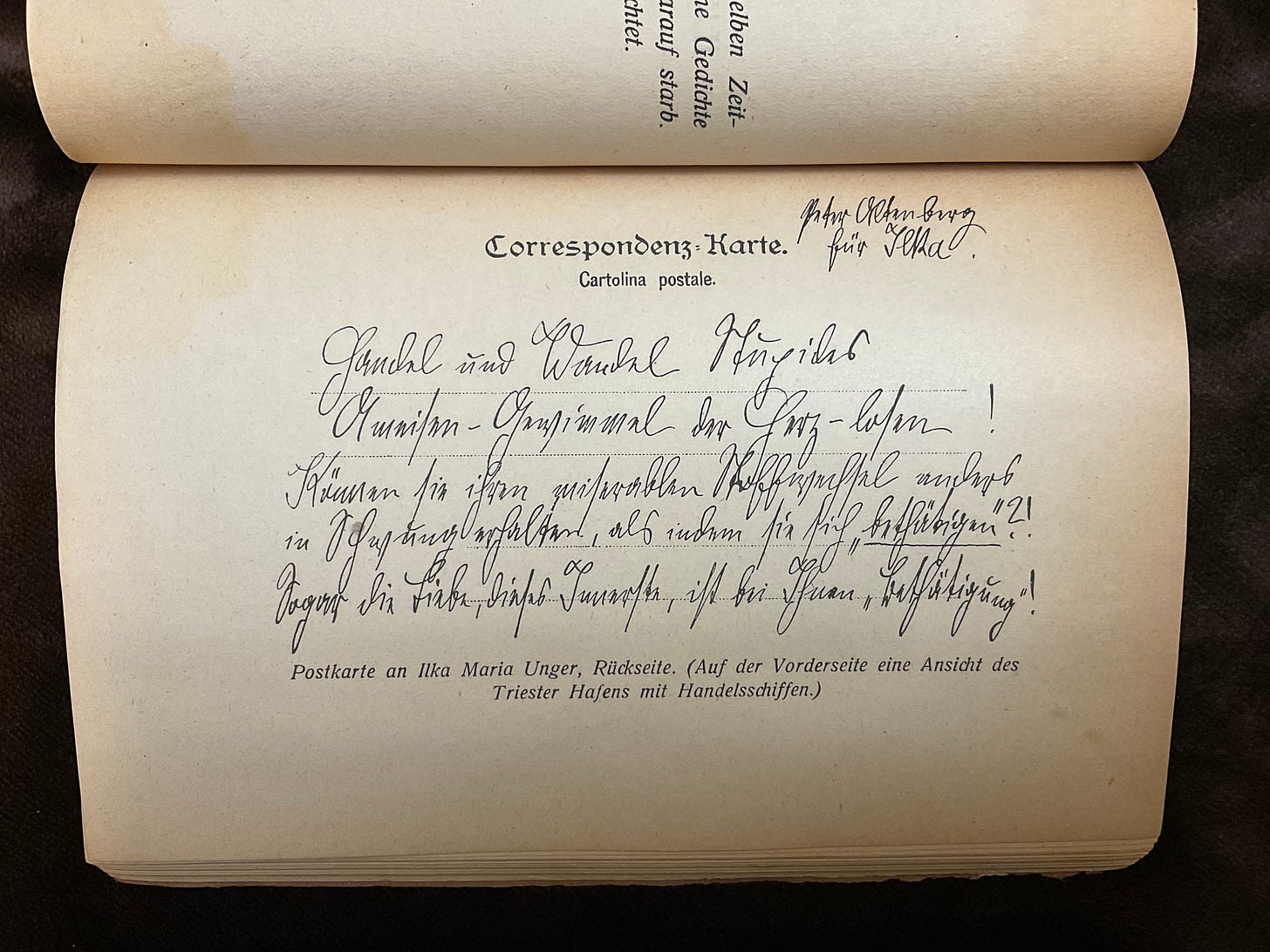

Peter Altenberg used napkins, the backs of postcards, and any other scraps of paper that came to hand to dash off poems and brief tales. He often did this while seated in one of Vienna’s many cafés, drinking coffee heaped with schlagobers. He contributed feuilletons to the local journals. These were literary trifles: talk of the town, charades, art criticism, short fiction, etc.

Thomas Mann characterized Altenberg’s epigrammatic style as resembling “telegrams.” The translator of a 2005 selection of Altenberg’s stories entitled Telegrams of the Soul refers to them as “postcard” fictions, a nod to experimentalist composer Alban Berg’s (1885–1935) non-tonal “Five Orchestral Songs After Postcards by Peter Altenberg.”

Many of the stories Altenberg wrote were semi-autobiographical. Some are so elusive that, without more clues as to what was going on at the time, they will remain forever indecipherable.

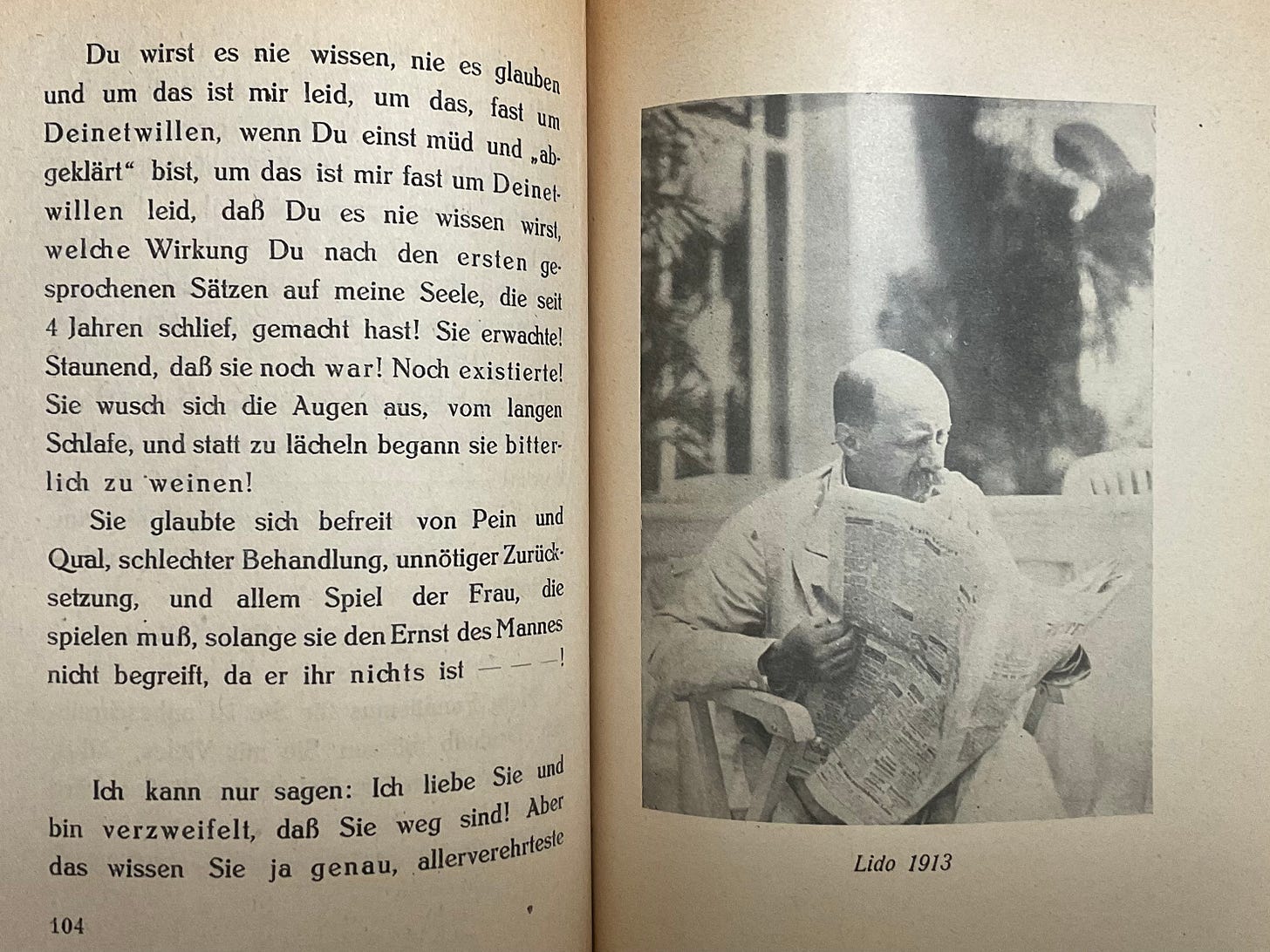

I lived in Austria for several years and returned in November 2024 to scour the antiquarian bookshops in Vienna and Salzburg. Among the treasures I found was a copy of Das Altenberg Buch, published in 1921, which consists of letters and other ephemera the compiler, Viennese playwright Egon Friedell (1878–1938), managed to collect shortly after Altenberg’s death.

Friedell constructs a mosaic of Altenberg’s life, adding cartoons, photographs, scattered anecdotes, and reminiscences that were provided to him by other Secession-era artists who knew Altenberg well, such as minimalist architect Adolf Loos (1870–1933) and litterateur, Hugo von Hofmansthal (1874–1929).

Whether Altenberg’s stories are under 50 words or over 100, they are all as long or short as they need to be. There is one — not included in Telegrams of the Soul — that I have translated below. It is a two-sentence ghost story and homage to Empress Elisabeth of Bavaria (affectionately known as Sisi), who was murdered by an Italian anarchist on the banks of Lake Geneva in 1898:

“Where are you going, restless woman in my dream?” — “Away from all the lies.”1

There were many lies circulating about Sisi in Vienna following the death (in a murder-suicide) of her son, Crown Prince Rudolf in 1889. The incident strained relations between her and Emperor Franz Joseph, and she spent most of her last years separated from him. But even before that, salacious rumors circulated that she had engaged in an affair with Hungarian Count Gyula Andrássy.

Another Altenberg “postcard fiction,” which is less than 50 words long, is titled “Poverty.” A poor girl confides to the author that she needs to visit the doll doctor in the Fifth District, because a lady gave her only the top half of a doll. When the author expresses surprise someone would be so rude as to give a mutilated doll to a child, the girl replies that, if it had been intact, it would be too valuable to give to a beggar’s daughter.2

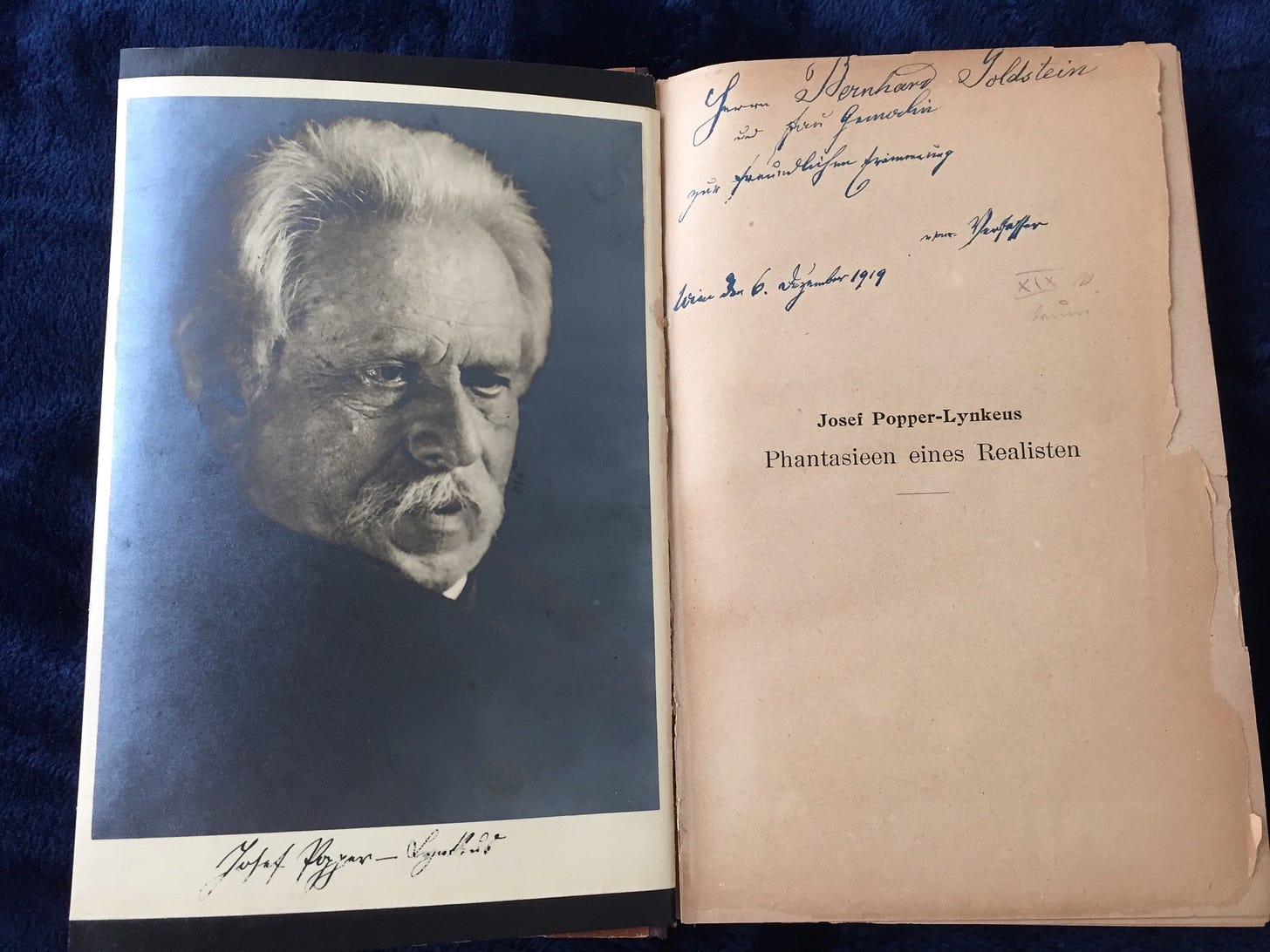

Josef Popper-Lynkeus (1838–1921)

Josef Popper-Lynkeus (the pen name “Lynkeus” came later) was the uncle of Austrian-British philosopher Karl Popper (1902–1994). He was an inventor, engineer, and social reformer. Born in Bohemia, he spent most of his life in Vienna. There is a monument commemorating him in the park fronting the Vienna Rathaus.

Popper-Lynkeus wrote short fantasies. In 1899, he published a collection of these called Phantasien eines Realisten (Fantasies of a Realist), which went through twenty editions.

One of the stories in it is exactly 107 words long (7 words over the limit for a “drabble”). It is called “The Light of the Philosopher Mozi.” In it, the inhabitants of a valley witness a supernatural light suffuse Mozi’s features as he meditates on a mountain. When he descends, they ask about the source of the light: “As I sat on high,” he says, “I recalled that, long ago, a dear friend rebuked me.”3

Below I have translated another of his stories (less than 50 words long). It is included to show that not all these fantasies have magical elements to them. Some are simply short fiction pieces.

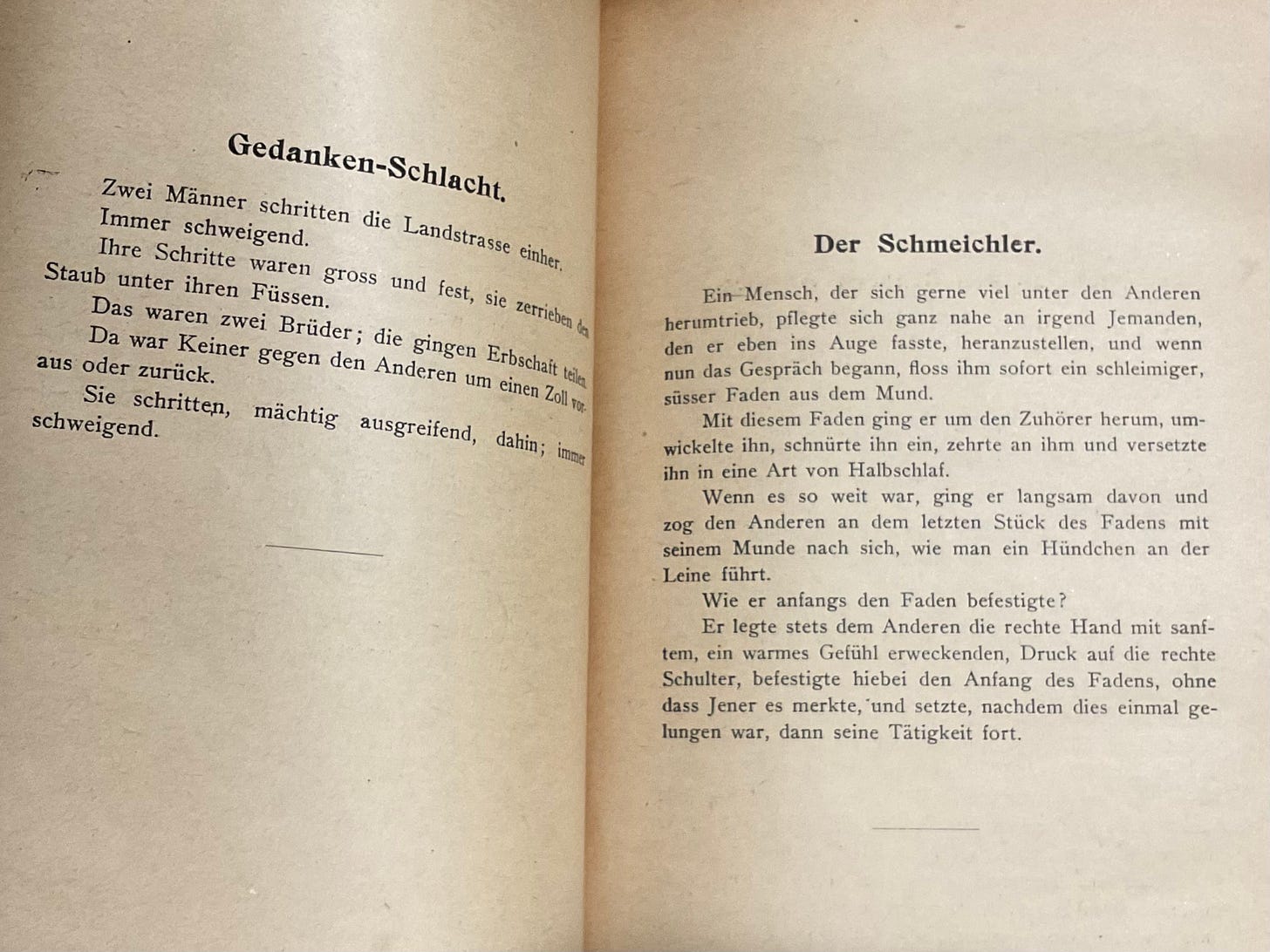

Battle of Wits

Two men walked down a country road in silence. Their steps were bold and firm. They trod the dust beneath their feet. They were brothers on the way to divide their inheritance. Neither walked so much as an inch ahead of the other. Thus, they strode toward their objective. Thus, they walked in silence.4

By contrast, the following is reminiscent of a tale by Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986):

Ibn Rushd

The philosopher Ibn Rushd (whom Westerners call Averroës) felt great pain in his final days whenever he tried to sit up. One night, he lay awake in bed. The door opened. A grisly face peered in, staring at him for many minutes. Then it withdrew and the door closed.

At once, the door crashed open and the Angel of Death floated in, hovering over the bed, eyes flashing, unsheathed scimitar glinting in the candlelight.

“Ibn Rushd!” the angel said. “On which side of the scale lies heaviest your heart?”

“On yours,” the man replied, rising in agony and extending his arms lovingly toward the angel.

The Angel of Death sheathed his sword, lifted Ibn Rushd from the bed, cradled him tenderly in his arms, and bore him off into the unbounded night.5

Fables, Sagas, Legends, Märchen

Popper-Lynkeus’ short stories were commonly called Fabeln (or “fables”). The word fable derives from the Latin fari, meaning to “speak” or “tell.” A fabula is therefore a “tale told,” usually a fantastic one, which enforces a moral. However, it can also simply be a tale told to excite wonder (cf. the fabled wealth of Croesus). In other words, it is a short fantasy.

Sometime in the twentieth century, scholars went against two millennia of precedent to assert that the word “fable” only refers to a short moralizing tale involving anthropomorphized animals, objects, or forces of nature, like Aesop’s Fables or the tales of Reynard the Fox. Moralizing tales not fitting this criterion (so the argument went) are parables. (Wikipedia champions this definition, even as Wiktionary confutes it.)

The word “fable” has been used for centuries to mean a short tale, usually a far-fetched one (but not necessarily so), which often (but not always) has a moralizing purpose. A cursory examination of the witnesses for the headword “fable” in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) will demonstrate how odd this attempt to clarify our understanding of the word is.

While a “fable” was a tale told orally, like a Norse “saga” (German Sage), a “legend” was a tale written down. The word derives from the Medieval Latin legendum, meaning “that which is read” (Latin: legere). German sagas and legends mostly revolve around historical personages, such as Charlemagne, or mythical heroes, like the dragon-slayer, Siegfried. Sometimes they are etiological stories about famous landmarks.

In 1853, Ludwig Bechstein published Sagen aus deutschen Landen (Sagas from German Lands), which included stories about Martin Luther, Doctor Faust, and the Lady of the Lorelei Rock, who lures sailors on the Rhine to their death with her song. Bechstein borrowed heavily from the Grimms’ collection, Deutsche Sagen (German Sagas), published in 1816.

Märchen is often translated as “fairy tale(s),” which is not entirely correct. It stems from the Medieval German Mär, meaning “news” or “tale.” Märchen is a diminutive, meaning “snippet of news” or “little tale.” Like most diminutives, it is neuter (das Märchen), but does not change morphologically in the plural (die Märchen). A more accurate rendering of the Grimms’ 1812 Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales) would be something like “Brief Tales for Children and Households.”

Though many of the stories in Kinder- und Hausmärchen (hereafter KHM) are what we think of today as fairy tales (involving dwarfs, monsters, witches, enchanted forests, etc.), it also contains jokes, folk tales, ghost stories, homespun wisdom (“The Old Man and his Grandson”), and religious stories (usually involving manifestations of Catholic saints). The 1812 edition of KHM also inlcuded tales that were so horrific that they were removed from subsequent editions.

One of these is called “Wie Kinder Schlachtens miteinander gespielt haben” (How Some Children Played the Game of Slaughtering with One Another). There are two versions of it. Many of Grimms’ tales have two variants, such as Little Redcap.

In the tamer version, two boys (brothers) watch their father slaughter a pig. One brother then pretends to be a butcher and slits the other’s throat. The boys’ mother, who has been washing the baby in the house, overhears this. She runs outside, sees what has happened, and stabs the surviving son to death with the same knife. Meanwhile, the baby, left unattended, drowns in the tub.

The more gruesome version is also the more interesting, because it reads as if it might have been based (at least partially) on a real incident, perhaps lifted from court records. Both of the Brothers Grimm studied law; and their father, Philipp, was a lawyer.

In this version, which is set in West Friesland (an uncharacteristically specific detail), a group of boys and girls between the ages of five and six pretend they are running a butcher’s shop. One boy is the butcher, another the pig, while a girl is chosen to collect the blood in a bowl. A councilman witnesses the murder and hauls the killer off to court. But the magistrates declare the boy innocent, because, when offered a choice between a gold coin and an apple, the boy “laughingly” takes the apple, “proving” he does not have a wicked heart.6

Duden’s Dictionary of German Etymology defines a Märchen as “a brief narrative without any link to a historical person, a literary fiction (to include poetry), an invented tale.” This would have been how German-speakers would have understood the word during the Vienna Secession.

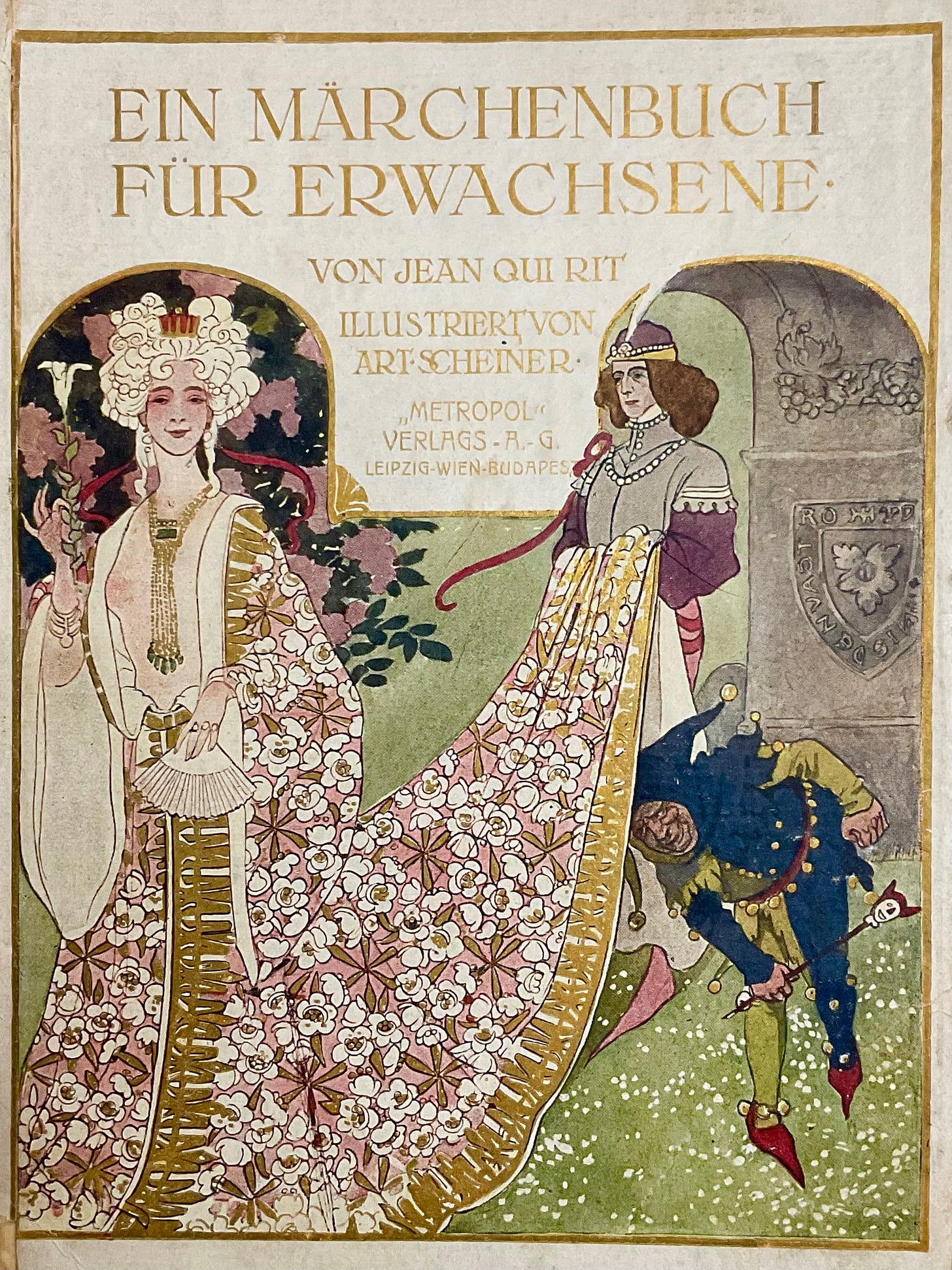

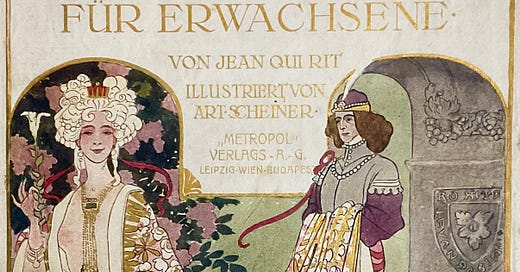

The thumbnail of this essay is a photograph of the cover of a pornographic anthology called Ein Märchenbuch für Erwachsene (A Book of Brief Tales for Adults). It was published c. 1909 by an author (or authors) who wrote under the pseudonym, Jean Quit Rit (“John Who Laughs”). It contains many beautiful illustrations produced by Secession artist Artuš Scheiner (1863–1938), but they are so graphic that, even by today’s standards, I do not think I should post them here.

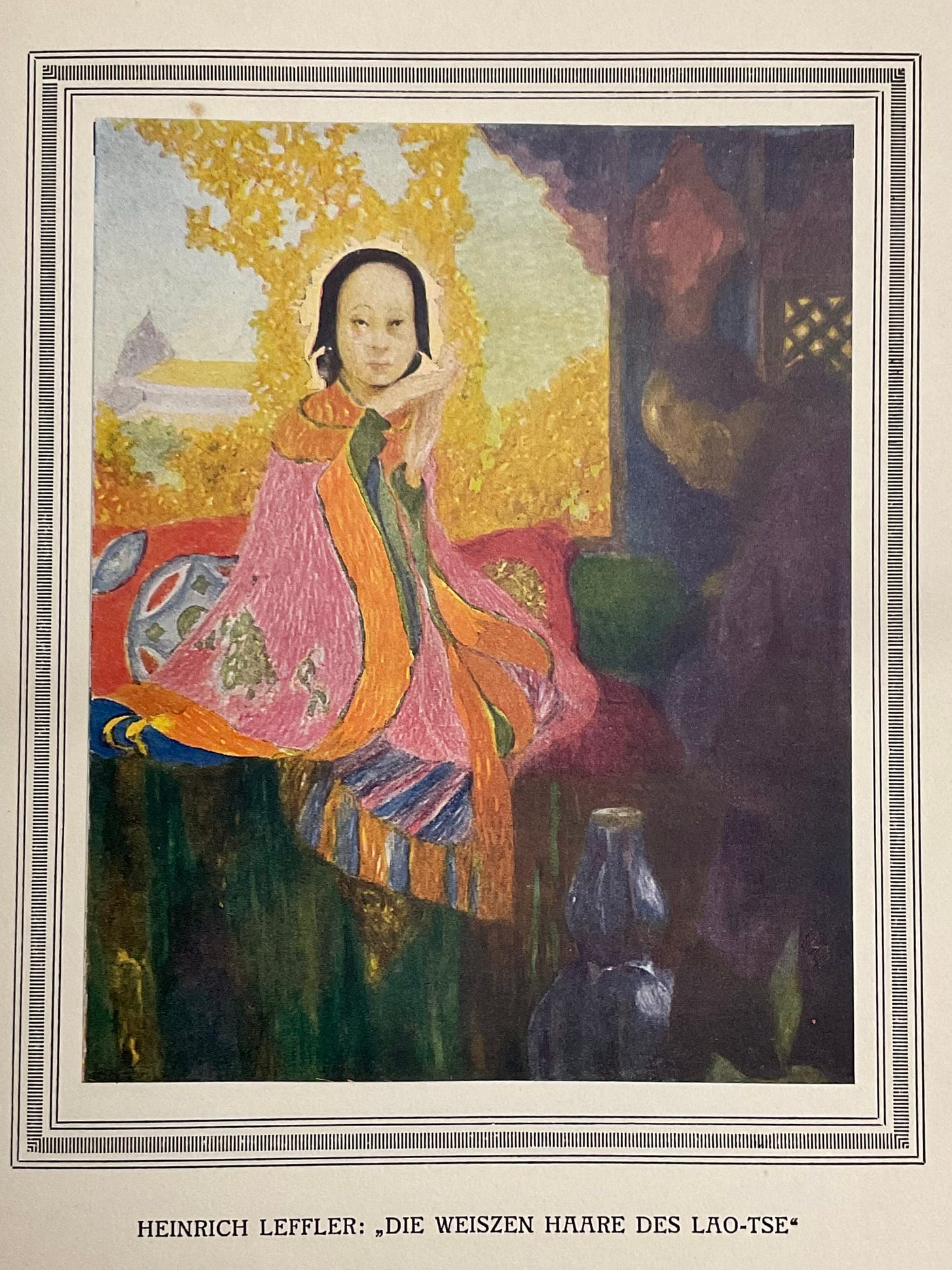

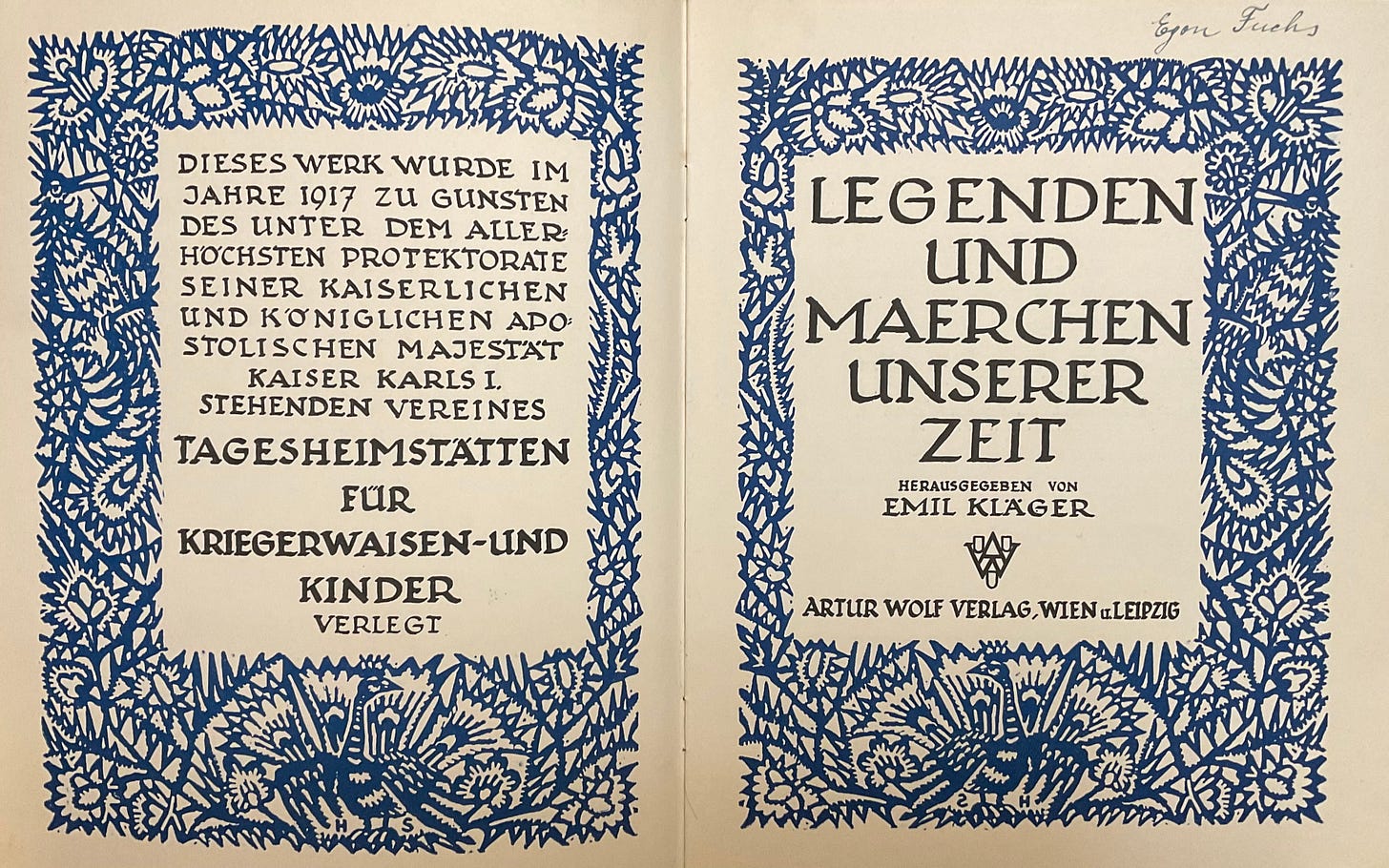

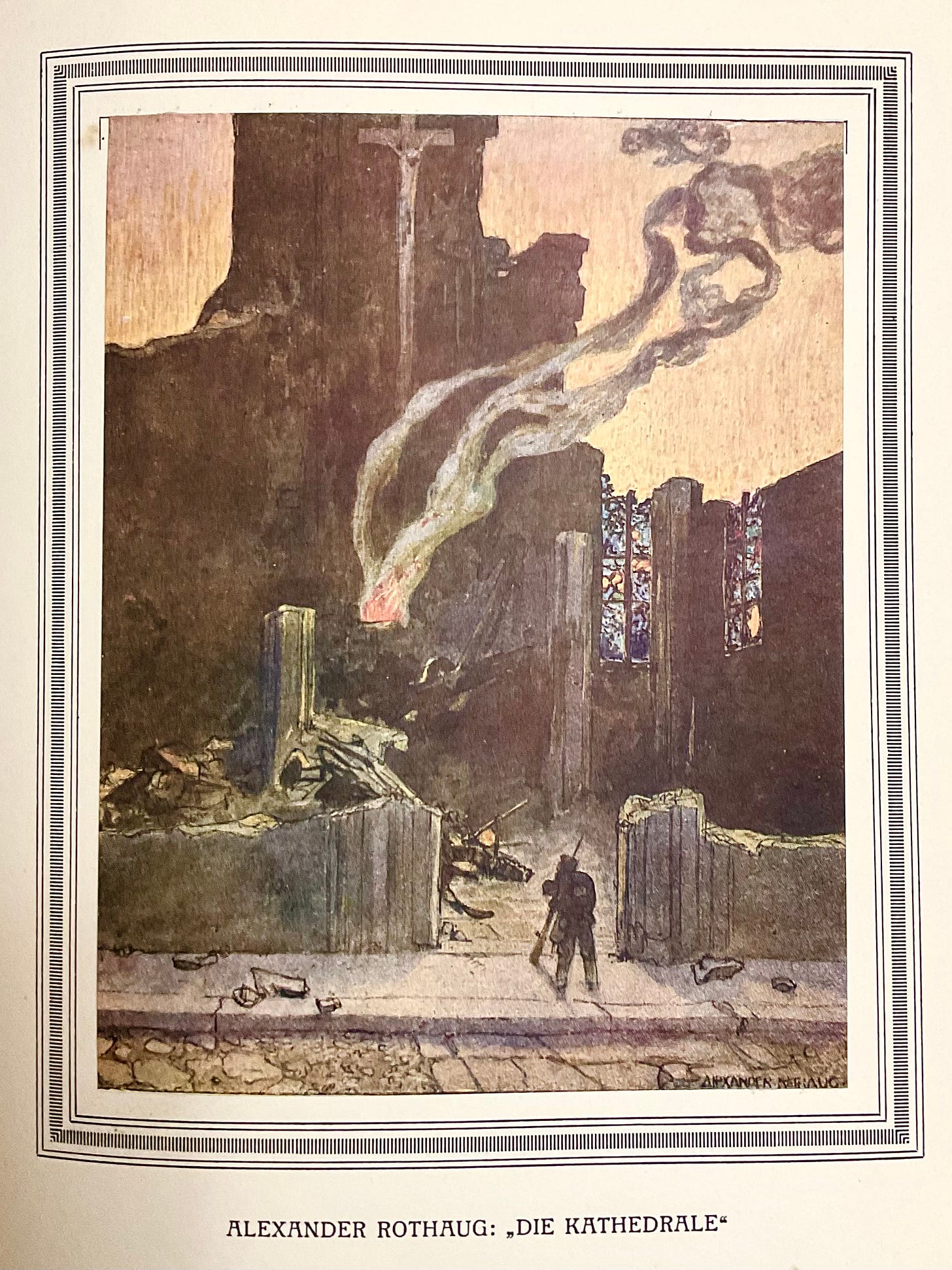

Another book in my collection is a 1917 anthology called Legenden und Maerchen Unserer Zeit, meaning “Legends and Tales of Our Time,” which includes a story by Popper-Lynkeus. Although the book contains some traditional fairy tales, many of the stories are urban and pastoral romances, poems (to include one called “War Poem”), and short tales about WWI (which was still in full swing at the time of publication).

What’s in a Name?

Renaming an old mode of storytelling is not exactly inventing, discovering, or perfecting it. The “Parable of the Talents” is a masterpiece of literary compression embedded in a frame narrative. In that regard, it resembles “Before the Law,” a parable that the prison chaplain relates to Josef K. before his execution in Franz Kafka’s Secession-era novel, The Trial.

Some might argue that, unlike Kafka’s story, a Biblical parable does not really count as flash fiction, because it is part of a religious text, and calling it “flash fiction” is an anachronistic retro-projection. Even those who concede that a Biblical parable formally meets the criteria for flash fiction, are often inclined to dismiss the “older stuff” as thin on style and woefully lacking in psychological sophistication and depth.

Those tired “baby shoes” of Hemingway’s are often trotted out to show the dizzying heights that modern flash fiction is capable of achieving. But the myth of Hemingway’s authorship of the six-word story credited to him has been soundly debunked. “For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn” first appeared almost verbatim in the Spokane Press in 1910, when Hemingway was seven; and, by 1921, the phrase “baby shoes, never worn” had become such a tear-jerking cliché that humorists were parodying it in the press. (See “For Sale: Baby shoes, never worn”.)

German has compound words that must be broken out when translated: Kraftfahrzeughaftpflichtversicherung, for example, means “motor vehicle liability insurance.” Wikipedia defines a “drabble” as a story of precisely 100 words (no more, no less). Is a 100-word German story no longer a “drabble” once translated? Some might say Wikipedia is wrong, and that a “drabble” does not have to be exactly 100 words. If that is the case, then what is the definition of a “drabble”? And what is gained by using the word?

The term “flash fiction” has become firmly rooted in the public imagination since its first appearance in 1992, but the speciously academic jargon that keeps cropping up around it is creating the illusion — at least online — that flash fiction is not so much a style of writing as a kind of app that needs to be routinely updated to unlock its new and enhanced features. The works of dead authors in such a climate are either viewed as irrelevant or useful only for training AI to crank out more flash fiction.

With the passing into history of the Vienna Secession, there emerged a new intellectual current in Austria in the early 1920s that formed around University of Vienna Professor, Moritz Schlick (1882–1936), called the Wiener Kreis (Vienna Circle). It was made up of scientists and philosophers influenced by the ideas of Bertrand Russell (1972–1970) and Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951). The Circle helped advance the fields of mathematics, logic, set theory, and what we today call computer science.

It is interesting to note that, despite the Circle’s overzealous habit of classifying even unreal objects and their relationships into “sets” and “types,” its members never seem to have hit upon the notion of dividing Märchen into subspecies based solely on the number of words they contained: dribbles (50 words), drabbles (100 words), twitterature (280 words), sudden fiction (750 words), flash fiction (1,000 words).

I imagine that if pressed as to why they had never done this, they might have furrowed their brows and alluded vaguely to the intelligibility but inherent meaninglessness of Russell’s proposition: The present King of France is bald.

Altenberg, Peter. “Wanderung” [Wandering] Was der Tag mir zuträgt. Translated by D.W. Davison. Editor Karl Kraus, Wiesbaden, Germany: Marixverlag, 2009. p. 105.

Altenberg, Peter. Telegrams of the Soul. Translated by Peter Wortsman, Brooklyn, New York: Archipelago Books, 2005. p. 31.

Popper-Lynkeus, Josef. “Das Licht des Philosophen Mih-tse” [The Light of the Philosopher Mozi] Phantasien eines Realisten. Translated by D.W. Davison, Leipzig, Germany: Verlag von Carl Reißner, 1918. p. 85.

Popper-Lynkeus, Josef. “Gedanken-Schlacht” [Battle of Wits] Phantasien eines Realisten. Translated by D.W. Davison, Leipzig, Germany: Verlag von Carl Reißner, 1918. p. 86.

Popper-Lynkeus, Josef. “Ibn Roschd” [Ibn Rushd] Phantasien eines Realisten. Translated by D.W. Davison, Leipzig, Germany: Verlag von Carl Reißner, 1918. p. 98.

The Complete Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm. Translated by Jack Zipes. New York, New York: Bantam Books, 1987. pp. 650–651.

I think there will always be critics who want to categorize and authors who object to such categories. That's partly because the critic is engaged in more analytical thinking, while the author is engaged in more creative thinking. The two types of thought are not opposites, but they involve looking at reality through a different lens. Analysis years for categorization. Creativity yearns for a lack of external restraint.

In my younger days, I read a lot of analyses of Greek mythology in which the critics made heavy use of saga and marchen as descriptive terms. Almost universally in that kind of writing, saga referred to material closer to history (like the Iliad) while marchen referred to the more fantastic stories (like the exploits of Perseus.. These are not the original German meanings, as you point out, but one could argue that they meant something specific in the literary criticism of a certain era.

I love this, Daniel. Really fascinating history, and the illustrations are gorgeous. And, yes, I never understood the need for intensively classifying anything and everything to do with the arts in the first place (mini-movements and microgenres are my pet peeve, whether in literature or music). These are by definition subjective, creative realms, and should defy taxonomic classification, but our instinct is to shove them into smaller and neater boxes anyway. Perhaps another way to slice and dice our own identities by identifying with ever more niche cultural artifacts. But do they enhance our understanding or enjoyment of the work itself? I don't see how. I've often wondered what exactly is gained by focusing on the word count of a story at such a minute scale, and naming each new iteration. It can be a fun exercise to, say, set out to write a story that is exactly X words, but I wouldn't want to make a career of it or slap a label on it. After a while, as with any formula, you stop writing the story and the story starts writing you. This seems like a creativity killer. Just say what needs saying.

And thank you for correctly defining "fable" and "saga." One of the (many) things that has baffled me about the traditional publishing world is its weird insistence that the word "saga" should apply almost exclusively to family sagas. I'm not sure why that distinction came about, but it always seemed arbitrary, like insisting all fables must be about anthropomorphized animals. Luckily, we don't have to work under anyone else's narrow definitions :-)