Impeding the March: How Prioritizing Visual Description Over Storytelling Mars Otherwise Exceptional Writing

An Essay

Although stories with no “visuals” are difficult to visualize, there’s something to be said about authorial restraint. When a narrative wanders through a mist of sesquipedalian adjectives and overwrought metaphors describing one empurpled twilight after another, it fatigues the mind and makes what we thought would be an hour’s diversion into a tedious slog. We skip ahead, searching not only for a plot but a clue as to where it’s going.

Authors who embrace Keats’ dictum to line every rift with ore should keep in mind that he died two hundred years ago when people had longer attention spans. If every sentence is cut from Pentelic marble, we know not where to direct our gaze. And as with rich desserts, there will come a point when even the heartiest of readers will push the plate aside and say, “I’ve had my fill.” To quote Samuel Johnson: “Read over your compositions, and wherever you meet with a passage you think is particularly fine, strike it out.”

This is the first in a series of essays concerning modern authors whose passion for visual description—not olfactory, not tactile, not auditory, but visual description—bogs down their stories in a sump of unnecessary detail. Many of them are young and have admittedly exuberant imaginations, but they lack discipline and have apparently never been told that the overgrown hedge mazes they construct would be easier to get through if they were trimmed from time to time.

Some of these writers are praised to the skies as models of literary excellence but they are not widely read. And it shows. They struggle with pacing, mistake prolixity for eloquence, and think it witty to use baroque language to describe disgusting things, such as turds floating in a toilet. But their chief fault is that they labor under a misguided belief that if they only add one more descriptor or subordinate clause to their tale, they will achieve a precise carbon copy in words of the tired and thrice-recycled images they have seen in films, video games, and graphic novels.

But writing is a Procrustean bed, which the awe-inspiring visions of even the most gifted of aphantasic storytellers will never fit into comfortably.

As bitchy as I might seem, I consider myself a sympathetic reader. I’m not interested in doing a hatchet job on another writer’s work. I don’t think it’s fair. It presumes they’re wrong and I’m right. We’re all honing our craft in our own way; and matters of taste and style will always be subjective. But because I was averse to calling out anyone by name (but needed an example of the kind of hyper-focus on visual imagery that this essay is addressing), I decided to create the following parody of the kind of bloated paragraphs that I’ve come across on Substack:

He stood on the balcony in the late afternoon, hands clasped behind his back and pressed against the broad leather belt around his waist, beneath which the tails of the fuscous, maroon long-coat that he wore flapped in the autumn wind. The matching tricorn hat on his head cast a shadow on the wall to his immediate left, which was directly opposite the setting sun. The base of the hat’s rhomboid shadow slanted downward at a forty-five degree angle, under which the silhouette of the man’s bearded face could be seen, chin lowered (almost to the manubrium), as he pensively contemplated the import of the message in blood-red letters written on the parchment lying on the surface of the warped wooden table in the center of the somber, torchlit room behind him.

(Yes, it is an exaggeration. But not much of one.)

In many ways this trend of creating Dutch still-lifes in writing is reminiscent of the Victorian era, when, with no TV available and only limited access to photographs, daguerreotypes, pen-and-ink illustrations, and other visual media, writers like John Ruskin, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, and Charles Dickens supplied an eager public with reams of ornate prose, which painstakingly described every pediment and architrave of a Gothic cathedral or every shade of rose one might glimpse on the eastern horizon at break of day.

But by the 1920s (after the Great War), literary tastes began to change and authors who continued to write in such an “Asiatic style” were derided as anachronisms or chalked up as holdouts of the Yellow Nineties. If a picture’s worth a thousand words, a moving one is worth millions (as MGM, Paramount, and Universal studios were soon to learn). It was inevitable that cinema would contribute to a shift in the way authors, who wanted their books read instead of merely praised, told stories.

They realized that compression was a virtue, and that they would need to simplify and streamline their prose. I’ve never been interested in researching the history of the publishing industry in the mid- to late twentieth century. But I had an college internship in the Nineties as a slush reader for an academic press with a fiction imprint. And I’ll never forget the day I overheard an elderly developmental editor ripping into a mercifully forgotten author of “non-genre literature,” who sat listening with his arms folded and a faraway look on his face:

“Why did you expend wells of ink describing every crease and contour of the bathroom towel the lady threw on the floor? Does this have any bearing on the plot? Does she suffer from a derangement that causes her to fixate on such things? Was there blood on the towel? Did the act of casting it down stir up a Proustian memory, like a madeleine cake dipped in tea? If not, leave the towel on the floor and move on.”

In his Biographia Literaria, Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote of a primary and secondary imagination. He believed that the primary imagination had a compositive or synthetic quality that enabled it to reflect (as in a mirror) the created world, while the secondary imagination, which not everyone possessed, enabled artists to act a demiurge and re-create creation. He asserted that works of imagination should be written “in a plain style.”

But while “Kubla Khan” and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner are limpid and beautiful, Coleridge apparently thought that expository prose would be more convincing if it were less clear. His reminiscences, critical essays, and philosophical musings are often abstruse to the point of impenetrability. Classical rhetoricians used to refer to this style as periphrastic, perissological, or pleonastic. But even these terms have all but fallen by the wayside.

In his essay “On the Prose-Style of Poets,” the literary critic and painter, William Hazlitt, a friend and admirer of Coleridge’s, describes the poet’s stilted prose in a delicious sendup:

[Coleridge’s] style is not succinct, but incumbered with a train of words and images that have no practical, and only a possible relation to one another—that add to its stateliness, but impede its march. One of his sentences winds its “forlorn way obscure” over the page like a patriarchal procession with camels laden, wreathed turbans, household wealth, the whole riches of the author’s mind poured out upon the barren waste of his subject. The palm-tree spreads its sterile branches overhead, and the land of promise is seen in the distance.

Though Hazlitt is writing criticism, his painter’s eye shows through. He doesn’t overdo it by describing the camels’ withers or the dust their hoofs kick up. There’s no mention of the sun’s rays glancing off the riders’ golden bangles. With a few deft brushstrokes, he has created a sublime image that we feel we are part of. It is a set-piece, but a vibrant one. There is movement. There is vitality.

The German dramatist and literary critic Gotthold Ephraim Lessing published a book-length essay in 1766 entitled Laocoön, or the Limitations of Poetry. In it he argued that the visual arts fell under the purview of space, while the literary arts were subject to time. At first blush this reads like a typical Enlightenment pronouncement, a neat compartmentalization into Aristotelian categories of ideas that defy systematization.

But the more one ponders what Lessing was trying to say, the more interesting it becomes—not only as an artistic theory but as a conceptual framework for understanding our own modern dilemma of straddling a so-called “real” world (of spatial extension), which we live in, and an overly visual “online” world that we are becoming increasingly incapable of unplugging from.

Imagine if your eyes and occipital lobe functioned in isolation of the other faculties of the mind. Would such a limited brain, a vegetative one, be capable of comprehending time in the same way we do with our intact cerebral cortex? Or would the eyes absorb light while leaving it up to the occipital lobe to register the position of objects and their relationships with one another as static snapshots or two-dimensional transparencies, which, when overlaid, create a sort of atemporal stereographic map?

When we stare at our smartphone and “snap out of it” hours later, only to realize we’ve wasted half the night, did our consciousness withdraw during that “time” into the occipital lobe (“as the snail whose tender horn being hit shrinks backwards in his shelly cave with pain”)? Did our spatio-temporal world collapse “monetarily” into an exclusively spatial one? When we dream, we are shunted from one visual experience to the next, like a maniac clicking a TV remote. But though we feel the expansiveness of this oneiric space, our sleeping bodies remain enveloped in a timeless cocoon.

“Movement” is governed by verbs. And many faiths and philosophies discuss the power and diachronic nature of the verb writ large, which is to say the logos or word. All verbal arts, to include literature, are rooted in action. “Action” is indissolubly linked to time: “And the Lord said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light.”

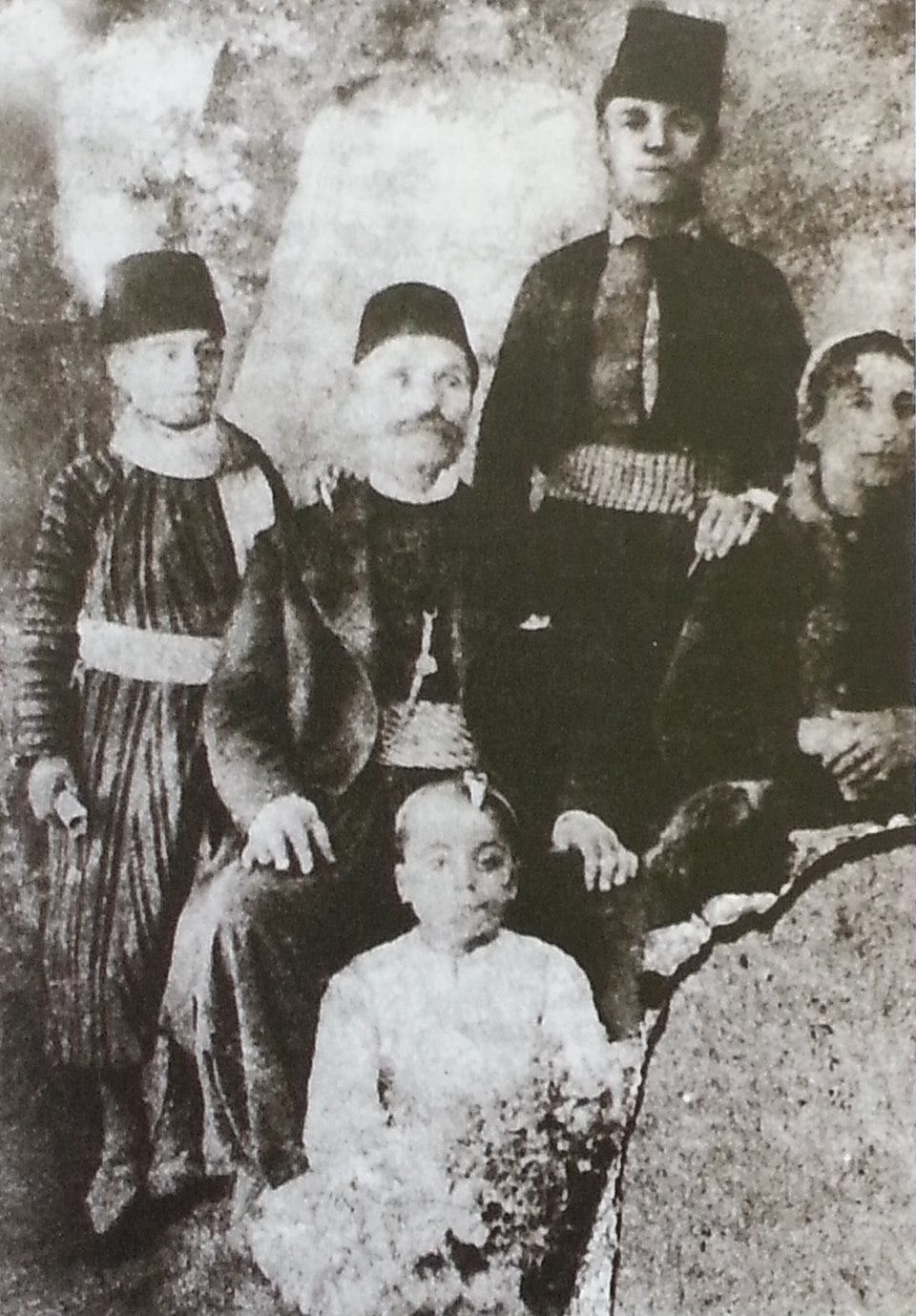

Below is a brief tale that would seem to confute the claim I made at the beginning of this essay that a story with no visuals is difficult to visualize. It is taken from a biography of the Lebanese-American poet Gibran Kahlil Gibran. It is a memory of a conversation he had with his Maronite Christian mother when he was only ten years old and living in the city of Bsharri on the cedar-clad slopes of Mount Lebanon:

She said, “He [Jesus] was the greatest of all great poets. He who wrote not one single line save that line upon the sand.”1 And in my perplexed ignorance I asked her, “But how can any man be a great poet without writing lines?” With a smile she said, “Who knows, my child. Perhaps we are the lines He wrote.”2

This is a reference to John 8:6–8 in which Jesus confronts the Pharisees who have condemned a woman to death for adultery. Jesus kneels and writes something in the sand, which later Christian theologians allege was a message that convinces the woman’s accusers that she is guiltless.

Gibran, Jean & Kahlil G. Gibran, Kahlil Gibran: Beyond Borders. Northampton, Massachusetts: Interlink Books, 2017.

I love classic literature, but I think you make a good point here. Sometimes it feels like an author is trying to micromanage exactly what the reader visualizes, which is an impossible task.

I don't personally mind vivid visual descriptions within reason, though I've encountered more than a few that have turned into instruction manuals rather than just painting a scene (don't get me started on the cataloging of flowers in a scene!!!). I think this arises more from insecurity on the part of the author than anything else—it can be hard to let go of a character or scene and trust that readers will see it how the writer wants, so the writer tries to brute force the picture into the mind's eye. But the truth is, readers will never see what we see, so it's all for nothing anyway, and a lightly sketched scene can be just as evocative as a thoroughly documented one without all the fuss.