On Witches in Literature

What are these, so withered and so wild in their attire, That look not like th'inhabitants o'th'earth And yet are on't?—Live you, or are you aught That man may question? You seem to understand me By each at once her choppy finger laying Upon her skinny lips. You should be women, And yet your beards forbid me to interpret That you are so. (Macbeth, I.iii.40-49)

Having successfully completed my enlistment in the United States Army in 1993, I moonlighted the following year in college as an emcee at a gay bar in Bloomington, Indiana, where I quoted the above lines from Macbeth to a gaggle of drag queens backstage one Friday night as they prepared for a number. One of the performers (my quondam lover) responded by saying “Fuck off, girl!” while applying mascara. I had very few lines of Shakespeare memorized at the time, but I had memorized that bit about the witches in 7th grade, not because I knew what all the words meant, but because I liked the way it sounded. And I will never in this lifetime be afforded another sovereign moment like that to utter those lines.

My interest in magic and witchcraft goes back to my childhood, when my parents and elders told me that witchcraft was something sinful and wicked, like homosexuality, and that I should avoid it, lest I lose my soul. When they said such things, my eyes narrowed; and I pressed for details. How could I avoid something so horrible, I asked innocently, if I didn’t even know what it was? There were the green-faced witches in cartoons, who were simply ridiculous, and not particularly threatening. There were evil witches in fairy tales, not to mention the ones in children’s stories like The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe or The Wizard of Oz. But in those stories, there were good witches, wizards, soothsayers, etc. and no one really explained to me how it was that doing “magical” things was evil per se, if there were good characters doing “magical” things as well. It was very confusing to me as a child when churchgoing adults would consult fortune tellers at the state fair, or study their horoscopes in the newspaper, and then hypocritically nod their heads vigorously in agreement on Sundays when the priest declaimed against such things.

This essay is not about witchcraft. It’s about depictions of witches in literature, which is itself a really broad topic. Therefore, I will confine my remarks to some observations about two authors and their depictions of witches. I’m using these authors as stepping stones for a discussion that has no objective. This essay will end as abruptly as it began. It’s more like a friendly chit-chat I might have with a stranger while sitting outside a bar, my beer covered with a coaster as I smoke a Black and Mild.

I’m new to Substack and, thus far, I’ve only posted stories—other than the intro essay. I’d like to change that over the next few months and post on topics that interest me and that I hope I can interest others in. I think I’ll call this series of essays “Marsh Lights in the Gloaming.” I’m in the process of writing a novella set in northern Greece in the early 20th century called The Witch in the Mountain Pass. I’ve posted Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 here on Substack—the last part earlier today. I’ve separately plotted out a novel about a Ruthenian witch living in Weimar Berlin in the 1920s. That story, which I’ve finished three chapters of, is called The Infinite Wall and I may post that novel here next year. I like writing stories about witches.

In Lord Dunsany’s novel The King of Elfland’s Daughter, a witch creates a sword for the hero by climbing a storm-blasted hill to collect thunderbolts that have fallen from the heavens. She arranges the thunderbolts (which look like palm-sized flints) into a line, and then recites an incantation over them. The rocks miraculously coalesce into a magic sword. I have multiple copies of this novel, because I’m a fanatical book collector. (I’ll talk about that in a separate essay.) The thing I like about this depiction of a witch is that the magic here is not explained or rationalized. To me, representing thunderbolts as stones is a lovely and poetic image. However, many fantasy writers these days—not all, but many—feel a need to create worlds that are governed by syncretistic systems of magic that sound (to them, at least) semi-scientific—as though their world were some Parmenedeian whole that reconciled all the seeming contradictions that we have to deal with in our own wacky world. I don’t know if this is a consequence of the popularity of immersive video games and virtual universes where everything is programmed in and there are no loose gaps or postern gates for marvels and unpredictability to slip in through, but I don’t find stories like these edifying or attention-grabbing. In fact, I think it’s boring and exhausting to pick up a novel that devotes the first 75 pages to explaining how the fake science and fake alchemy of a fake universe is able to explain how the world’s city-sized steampunk ships fly hither and yon, fueled by crystals from provinces across the sea. The fact of the matter is that magic is irrational and can’t be explained scientifically, but that doesn’t mean there’s no truth to it, or nothing that we can learn from it, if it’s aptly woven into a story, as it is in the Harry Potter series.

Philosophy will clip an Angel's wings, Conquer all mysteries by rule and line, Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine— Unweave a rainbow, as it erewhile made The tender-person'd Lamia melt into a shade. (Keats, Lamia lines 234-238)

Were a modern fantasy writer to redo The Queen of Elfland’s Daughter, I have the feeling that there would be a push to preserve the poetic imagery, but that the writer would amend the illogicality of lightning bolts producing rocks by saying that, in this land of fairies, there is an element that is inherent at a microscopic level in electricity and that manifests itself as a stone once a lightning bolt, pregnant with this said element, strikes this fictional fairy-tale world; and these were the rocks the witch was picking up on the storm-blasted hill.

I’m not trying to “diss” modern fantasy or single out any writer for criticism, but it seems like much of modern fantasy fiction prioritizes world-building at the expense of storytelling and character development.

What are your thoughts? Please leave a comment.

Now here’s the second part of the essay. It’s a bit weird, because it involves a witch in literature and something that happened to me that I think to this day was supernatural.

The Metamorphoses by Apuleius contains the story of the Lamia that Keats based the poem quoted above on.

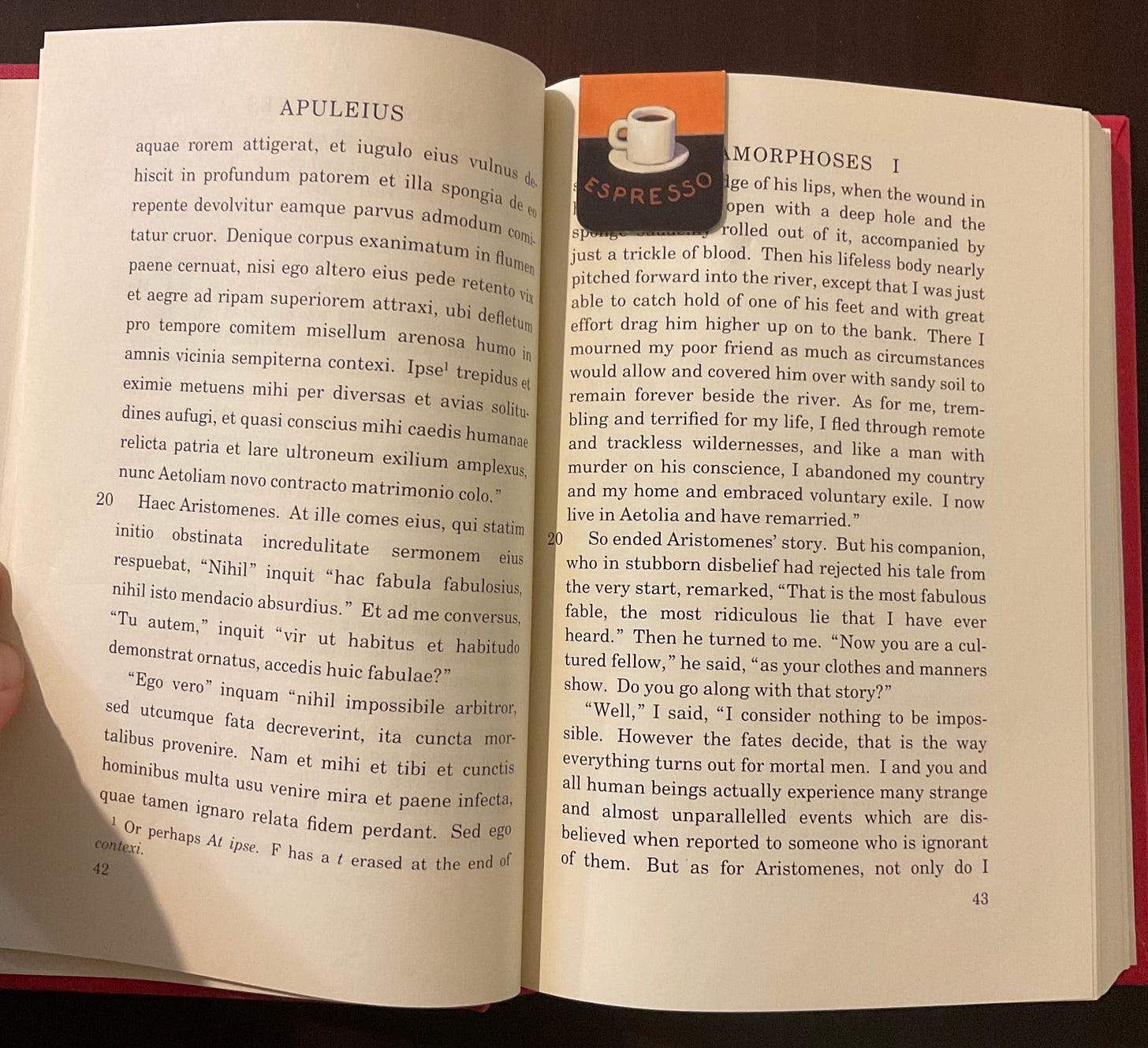

(Apuleius. Metamorphoses Books I–VI. trans. J. Arthur Hanson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Loeb Classical Library, 1989. Repr. 1996.)

This is the first book in my collection of Loeb Classical Library texts in Latin. But it wasn’t the first “Loeb” (as people call them) that I acquired. I bought it in New Haven, Connecticut, in 1997 a week after enrolling as a graduate student at Yale University for what turned out to be a brief flirtation with academia. It was a foolish purchase—one of about twelve Loeb books I bought the same day before classes had even started.

At one time in the middle ‘90s I entertained the notion of becoming a professor of medieval Arabic science and philosophy. I tell people that this is the type of thing you don’t bring up at cocktail parties, because it tends to kill the conversation. I was at Yale for less than a year. I simply pulled up my tent pegs and left—just left. I don’t exactly know why. There was a ghost of a suicide in my dorm room—a separate story that I haven’t the energy to write about tonight. The ghost of the suicide bothered me, but it wasn’t the reason I left—although I told people that it was.

Anyway, Apuleius is the first Roman author in my collection of Loeb Latin texts. He’s also the first author on the first shelf of the first bookcase in my library for a very simple aesthetic reason: I have more Latin (red) Loeb classical texts than I have Greek (green) ones, because I’m better at Latin than I am at Greek. And this calls to mind Ben Jonson’s famous comment on Shakespeare: “He had small Latin and less Greek.” I think it looks nicer to have an entire shelf of red books instead of having a smattering of green ones that shade into red, and then continue in red halfway along the next shelf. But, yes, the Romans came after the Greeks, so my arrangement is chronologically inaccurate.

Between 2000 and 2002, I lived in Minneapolis, Minnesota and worked for Cargill Corporation as an IT and database specialist. (I still can’t believe I used to be semi-adept with computers. I picked up Perl script, C++, Visual Basic programming, and Oracle database management in the 1990s when the world-wide web was relatively new. This wasn’t because I was interested in computers, but because I was fascinated with the history and evolution of symbolic logic, set theory, arrays, and binary mathematics. I couldn’t have cared less about the real-world application of such things.)

I lived in an efficiency apartment in downtown Minneapolis without a stick of real furniture. I used a card table to support my clunky computer and had a metal fold-out chair as the only chair in the apartment. I slept on a futon. The rest of the apartment was filled with cardboard boxes stuffed with my books. I had no bookshelves at that time, so I arranged my Loeb editions in a single row on a series of upside-down wooden vegetable crates that I took from a dumpster behind Trader Joe’s. I washed them out and covered them with a navy blue sheet. I decided that since I was alone and friendless in Minneapolis, I would finally buckle down and read my Loeb books to preserve my knowledge of Latin.

Apuleius was the first volume that I intended to read from cover to cover. I read each page in Latin and continued to the following page, if that necessary to finish the last sentence. Then I read the English crib on the facing page. Finally I reread the Latin page a second time, and looked up all the words I didn’t recognize, or I researched the grammatical constructs that were unclear to me in my Allen and Greenough Latin Grammar. This was a slow-going process. During this time I was working a night shift at Cargill near the purifying waters of Lake Minnetonka. (I actually saw Prince at a stoplight one day as I was heading in to work. He was in a dark Porsche dressed in bright colors, like a popinjay.) I never took a Loeb book with me to work, although I did have time to read at work when I was there, since I worked by myself. I was there as a contingency in case things went wrong. It was an easy job. While at work, I read novels or short stories by Dickens, Lovecraft, Asimov, Garcia-Marquez, etc. Well, one night something terrifying happened. And the event forever interrupted my reading of Apuleius in Latin.

I really hadn’t gotten far into the book. I made it to the end of the famous witch tale about Aristomenes and Socrates. The two bed down for the evening at an inn. Two witches enter the room. Aristomenes wakes up and watches in horror as one of the witches cuts open the throat of Socrates, removes his heart, and replaces it with a sponge. The witches then piss on Aristomenes’ face and disappear. Aristomenes is afraid that he will be blamed for his friend’s murder, so he tries to hang himself in the room; but the rope snaps and the innkeeper arrives at the door to see what the disturbance is. Aristomenes tells the innkeeper that his friend is dead. Suddenly, Socrates wakes up and is very much alive. Aristomenes is relieved and hugs his friend, who complains that Aristomenes smells like piss. The two leave the inn and travel along the road until they come to a stream. When Socrates leans over to drink from the river, his neck splits open and the sponge comes out. Blood gushes from the wound and he dies.

The top of page 43 in my Loeb edition of the book is where this episode ends. I still have a magnetic bookmark on that page, because it was the last page that I got to just before I headed into work one night in 2002. I received a call at my desk at around 10:00 PM: “Caller Unknown.” I picked up the phone and heard static. Then I heard what sounded like a man trying to speak through the static. I distinctly heard him say “I’m sorry.” The hairs on the back of my head stood up. The call disconnected. Within a minute there was another call—this time from an Indiana area code. It was my mother. She said that she was at the hospital and that my grandfather had just passed away.

I stopped reading the Latin edition of Apuleius after that, and have never gone back to it. I’ve since read Robert Graves’s 1950 Penguin Classic translation of Metamorphoses by Apuleius, which is usually translated into English as The Golden Ass.

Here is the abrupt point that I mentioned earlier where this essay ends…

Great essay, and I hope you'll do more like this in the future! I totally agree with your take on world building. It's a common disagreement between my husband and I when we read stories. He wants the magic system to make sense. I could care less about it if the characters are engaging. I am okay with not knowing, and I also admittedly don't understand science in any meaningful way in real life. So I'm fine with not understanding it when I read fiction as well.

The second part of this essay was very spooky. What made you stop reading Apuleius after that experience? Did they relate in some way to you? And also, a request that you write about your haunted room at Yale? Pretty please?

Very interesting! I think I agree about the world building in fantasy. I don't read very much anymore, but my frame of reference is mythology. Mythological systems don't generally worry about explaining the "science" behind the miraculous forces and events that drive their narratives. But they do have their own internal logic, and that seems to be reason enough to bind the characters and action of the story to their purpose.

And I agree with the others that you should definitely do some more essays!