Sly as a Fox

A Christmas Horror Story

The Sly Fox

Miss Beulah Rinehart, who ran the one-room Hoosier schoolhouse, told Bill’s class in 1920 that the reason southern Indiana was “crumpled up and rocky” was because, when the glaciers came down from Canada “around the time of Moses,” they reached the center of the state before “high tailin’ it back up north just before Jesus was born.” The consequence of this was that the land between South Bend (on the Michigan border) and Indianapolis (“smack dab in the middle”) got flattened out while the southern half became “crisscrossed with valleys, cricks, and hollers.”

To illustrate her point scientifically (which she pronounced “SINE-tif-cly”), she plopped down on her desk a ball of pink fishing dough dyed in hog’s blood—the very ball she’d use later that day to catch pond turtles with—and smoothed out one end with a rolling pin before dimpling the bulged-out section on the other with her thumbs, saying, “Just like that. You see? Mother Nature’s as sly as a fox the way she follows the Lord’s playbook.”

Sly foxes and rugged terrain were at the forefront of Bill’s mind, as he sat in the passenger seat of the Ford pickup truck on Christmas Eve, 1977, while his son (Pete) sped south down Interstate 65 through the slanting wisps of wind-whipped snow. The rust-bucket plunged between the wrinkled siltstone walls of a manmade canyon, which had been repeatedly dynamited sometime during the Eisenhower administration when the highway was being constructed.

“You’re gonna flip this goddamned thing over and kill us both,” Bill yawned. He’d been up since the wee hours of the morning.

“The snow ain’t stickin’ yet, Dad. I wanna get home and put the presents under the tree so I can get some sleep before the kids wake up.”

But sensing his father’s discombobulation, Pete slowed down to 50 mph. They were nearing the turnoff that led to French Lick, where Pete had built a house for his family. But his father, a widower, still lived in Muncie in the two-story colonial house he’d been born in. Pete’s wife Sandy asked her husband to bring “Papaw” down so the grandkids could seem him for Christmas. So Pete made the trek up north to fetch the old curmudgeon; but he’d waited until the afternoon, hoping the flurries would die down, which they never did.

In the wooly haze shed by the saline street-lamps on the right side of the road Bill saw a flat clearing made fluffy by the mounting snow. He knew exactly what used to be there; and his anticipation that they would be passing it caused the scar on his left eyebrow to itch and set him to thinking about his encounter with that devil fox on an autumn night long, long ago.

At the time of the story there had been an abandoned gas station occupying the lot. The family who’d owned the place had apparently gone bust after the Crash, packed up their belongings and tramped off to God knows where.

It was the height of the Great Depression in 1932; and Bill, who had just turned twenty-five, had never been happier. He hated work; and, since no work was to be had, he had plenty of time not to do it.

He was the oldest of four siblings and the laziest of the litter. But his Pappy was made of different stuff. The old man had been a railroad signalman since Teddy Roosevelt’s time and had managed to keep his job by steering clear of unions and speaking out against them at municipal gatherings.

One November morning, he came into son’s room and kicked the bunk until the deadbeat woke up. He told him a company was looking for able-bodied men south of Indianapolis to spend a week collecting scrap metal at a siding in Bargersville.

“Soup and lodging’s paid for,” he said. He handed Bill enough money to get him there and back. “I want you to go down and see about gettin’ work. We ain’t doin’ too shabby; but it’d be nice to have somethin’ other than chicken on the table of a Sunday evenin’.”

Bill filled a haversack with jerky, beans, a shaving kit, and a tin of pomade to slick himself up in case he had time to canoodle with a gal. He took the bus from Muncie to Broad Ripple Village, and rode the streetcar to Indianapolis.

That was where things went south (literally) because he was supposed to take an interurban to Greenwood, and from there to Bargersville. But he boarded a bus to Louisville, Kentucky, that stopped at a town called “Barkersville,” a whistle-stop built in the 1890s that would disappear from maps and men’s imagination by the time the first shots of WWII were fired.

In those days the roads in southern Indiana were meandering, unpaved, and bumpy. Some locals still maintained and operated toll bridges. The bus Bill was on popped a tire early in the afternoon; and it took the driver and the male passengers three hours to fix it. By the time they reached Barkersville it was already getting late. The bus came to a stop in front of the gas station, which was clearly no longer in service.

“You sure you wanna get off here?” the driver asked. “They ain’t nobody nowhere ’round.”

The man sounded like he was from Kentucky. Pappy liked to say that folks south of the Mason-Dixon line “were loud, yappy, and talked like idjits and hillbillies.” His son had taken this to heart and was prone to affect an air of Yankee condescension when conversing with Southerners.

“I’m here for work,” Bill said in a hoity-toity voice.

“Congratulations,” a threadbare man in the front seat said.

“Thanks,” Bill replied. He stepped down into the mud and gravel.

“I don’t even know why we still stop here,” the driver sneered. “Ain’t nothin’ left. A few families in the woods, I guess. Anyhoo—If you get lost, just hike back up to Crothersville where we came from, or down to Scottsburg. ’Bout the same distance as the crow flies.”

He shut the door and drove off.

The rumble of the bus died away as it rounded the corner and the only sound that could be heard were the dead leaves hissing in the frequent gusts and the rattle of a Coca-Cola sign nailed to a porch-pillar. Bill listened for a train whistle, so that he’d know which direction to head toward. But he heard nothing but the soughing of the wind. That seemed odd for a place with a railroad siding.

The front door of the gas station was still on its hinges, which surprised Bill, considering someone had gone through the hassle of prying off the lock to sell it. The creaking door opened inward. The place smelled of mildew. The front room was chaotic: overturned racks and shelves, an antique cash register dumped by the door (apparently because it was too heavy to haul away), and lots and lots of empty and shredded burlap bags and greasy strips of cloth.

Mounted to the wall under a glass pane were two maps and a bus schedule. It was too dim for Bill to read the map inside; so he removed his flashlight and switched it on. With his free index finger he traced the route from Barkersville up north to where he’d caught the bus in Indianapolis. Then he glimpsed over to the left and saw a place called Bargersville just south of the capital.—“Are you shittin’ me?” he shouted. He wiped his face and turned the flashlight off to save the battery. “Son of a bitch.”

He walked back outside to think. The road was covered with leaves and it was almost dark. Even if he used the flashlight and tried to hoof it, he ran the risk of wandering off into the woods or losing his footing and falling down a gully. True, there were farms and homes in these parts—and some might be electrified and have their lights on (or a coal-oil lamp burning). But the probability of a stranger getting shot in Indiana for trespassing on private property tended to become greater the farther south one was.

He went back inside and shut the door. The latch caught but did so loosely (a fact that saved his life later). The building was small and uninsulated. But, despite the wind having picked up, Bill sensed the weather would be unseasonably warm throughout the night. The three backrooms (where the family who owned the business had lived) contained no beds separate doors, partitioned as it was by plywood walls. But the back window was gone.

Bill uprighted two racks and shoved them against the opening to the residential section to make it less drafty. He planned to sleep by the counter where the till had been; but not behind it, since that could limit his motion in an emergency. Besides, the smell of wood rot behind the counter was more intense than anywhere else in the place.

He wadded up the cloth and stuffed it into his haversack to form a makeshift pillow. He pulled burlap bags around himself to use as blankets, knowing full well that this would make him itchy in the morning. Since he was constitutionally indolent, it didn’t take him long to fall asleep; and as he drifted off, he reasoned to himself that it was probably a good thing he had goofed up and gone to the wrong location, since, by the time he made it to Bargersville, the job Pappy wanted him to take would already be taken.

In his dream, a shaggy-bearded man was cradling Bill’s sleeping head in his warm lap. The figure agreed with Bill’s attitude toward the job. He drew a jagged fingernail across Bill’s cheek, which made a gash. But far from causing pain, Bill felt himself getting a hard-on. The creature lifted Bill’s head to its lips to more easily sink its teeth into the sleeping man’s brow. Bill moaned in ecstasy because he’d never known such pleasure.

And that’s when the loose latch swooped in to save the day. A blast of wind hit the door, which flew open and slammed against the wall so hard that it cracked the glass covering the maps. Bill gasped and opened his eyes. He heard a whimpering bark as a furry something sprang onto his stomach and used it to launch itself across the floorboards and out the door.

Bill’s face and brow were burning as he sat up. His vision was blurred with blood. In the moonlight he saw a fox standing at the threshold, growling at him. He grabbed his flashlight and turned it on. The eyes glinted yellow, as the thing turned and sprinted off. He couldn’t believe what had happened. The animal probably had rabies. Bill jumped up and ran outside.

He trained the flashlight onto the ground and saw in the diamond-shaped tracks of a fox in the mud. But to his horror, the farther the prints got from the gas station, the longer they became until his flashlight illuminated the cloven-hoofs of something two-legged that disappeared abruptly, as if it’d vanished or taken flight.

He went back in and fetched the haversack. Then he exited and walked around the building looking for a source of water. There was an old trough out back but it was full of gunk. He wiped blood from his eyes and waited for them to adjust to the dark. He espied the outlines of a rusty pump and went to it. He worked the handle until he heard the suction drawing water up from the well. He washed his face; pulled a handful of greasy rags out of the haversack and cleaned them to use as bandages.

He removed his shaving mirror and used it and the flashlight to examine the wound. The cut on his cheek was nothing but a briar scratch. But whatever had bitten his brow had almost taken flesh off the bone. And to Bill’s horror, the punctures and indentations were not caused by fangs but human teeth.

Every time he washed the blood away more seeped out wound. He did his best to dress it, but he’d forgotten to bring a needle and twine to make a suture; nor did he have matches to build a fire and cauterize it. But after an hour of stanching, the issue slowed and eventually stopped.

By the time he was done, the wan sun was shepherding in a gray and overcast day. There was no thunder or lightning but it started raining and wouldn’t let up. He could see the road clearly now, but his nerves were so shot that he couldn’t bring himself to walk on it, fearing that whatever had attacked him might be stalk him from the tree line.

The timetable in Indianapolis had indicated that a bus to and from Louisville ran once a day in each direction. So he waited on the front porch. He stood the entire time because he was afraid that if he sat down, he might fall asleep again. He tried hailing a passing jalopy, but the driver honked his Harpo-Marx horn and sped up to get away from the bloody-faced man whom he must have presumed was either a bum or a bootlegger.

But he didn’t have to wait long. By late morning, the headlamps of the northbound bus swept through the falling rain and Bill ran to meet it.

The bus stopped. Its windows were fogged. When the door opened, it was the same driver from yesterday. Sheepishly, Bill climbed aboard, tossing his coins in the fare-box. The only other passengers were a man and woman with their baby.

“They say this stretch o’ road is demon-haunted,” the driver remarked. “I was gonna tell ya that yesterday, but you was actin’ so high and mighty, I thought I’d let you find out yourself.” He laughed hoarsely, as he closed the door and drove off. “It looks like the boogeyman done boogied you up!”

When Bill made it home, he lied and told his father that he got roughed up in Bargersville by a pair of hoboes who didn’t take kindly to a young buck rolling into town to steal their work. Yes, Bill said, he was certain the man that bit him wasn’t mad with rabies. Bill had said this because he would have rather died than get that nasty stomach shot. But for several months afterwards, he became a regular churchgoer; and would pray day and night that he hadn’t contracted something fatal from that monster. But in the end, the only things that stuck with him from that horrid night were the scar on his brow and the memory of what had happened. . .

Pete slowed the pickup down as he turned off onto the two-lane road to Little York. He kicked it back up to 40 mph, even though the snow on the asphalt had not been plowed. The front lawns and rooftops they passed were decorated with lit-up plastic Santas, snowmen, and reindeer.

A small animal lay dead on the road and Pete guided the truck so the roadkill would pass cleanly between the wheels. But as they got closer, father and son saw a fox feasting on the carcass; and, when they were less than 20 feet away, the fox stood upright—a buck-naked man, eyes flashing yellow in the headlamp’s beams.

“Jesus Christ!” Pete cried out, slamming on the brakes.

The truck slammed into the man’s body, spun out and veered off into the ditch. It flipped over once and landed upside-down. The windows cracked and there was a scrunch of metal. Everything went black for Bill and his son.

When Pete woke up he was in a hospital room in French Lick, paralyzed from the waist down. Sandy and the kids were in the room and ran to his bedside in tears. The doctor explained that Pete had been in a coma for two nights. He’d been in an automobile accident and had suffered severe brain trauma.

“I’m afraid your dad passed away at the scene,” the doctor said. “There was nothing we could do.”

The nurses called Little York’s sheriff, who arrived with his deputy just before midnight. The sheriff said he didn’t want to cause undue stress but he hoped Pete might describe the events leading up to the accident. The weeping man replied that he could have sworn a man had been in the road; and he was afraid that he might have hit him.

“We think you hit a deer,” the deputy said. “The truck is totaled and the front hood’s caved in. But the only animal anywhere around was a dead possum in middle of the road. And your tread marks didn’t even go over it.”

The sheriff tapped the deputy’s shoulder, and motioned for him to leave. “We’re sorry for your loss,” he told Pete and Sandy. “It took us some time to get here; so we’d appreciate if we could get a statement before we leave. But we’ll step outside for a bit and give you both time to compose yourselves.”

“Thank you,” Pete said, wiping his eyes with his bandaged hand.

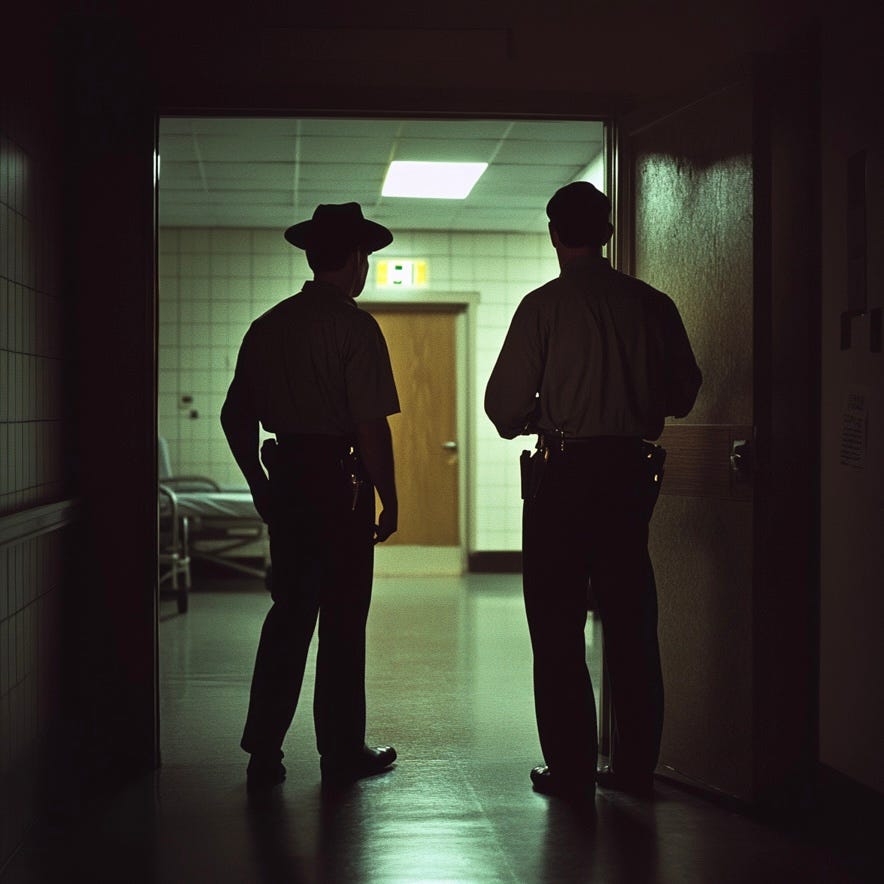

The sheriff and deputy lingered in the unlit ward.

“It just don’t make sense,” the young man whispered. “We was on the scene within 20 minutes. The dent on the hood looked to me like it come from a man, not a deer. But there was no deer tracks or footprints anywhere in the snow. And the only dead thing around was the possum in the street and the old fart in the pickup—”

The sheriff made a motion for the deputy to keep his voice down, so the family didn’t overhear.

“But there were paw-prints,” the sheriff said. “A fox was there. It walked from the possum to the overturned pickup and tippy-toed round the whole damned vehicle. And when it was sure there were no threats, it went back and ate more of the possum before dashin’ off into the woods.”

“Them foxes are sly little buggers, ain’t they?”

“They sure are.”

I knew that fox wasn't done with him yet! Very creepy, and wonderful characterization throughout. Enjoyed this one a lot :-)

Love that ending