If you’re joining us just now, follow the snake’s tail to the Prologue or climb a ladder to the Table of Contents.

Chapter 20: Brahman

Evan gave up struggling against the mass of black snakes that had immobilized him. The more he fought, the more uncomfortable he became. Behind him was a statue of Lord Shiva enthroned, occupying the place in the tower where the trunk of that tree had been, the tree he’d shinnied up and then back down to get here. He’d come this way, because he assumed the map leading to his heart was somewhere in this tower. But in order to continue his search, he would need to find a way out of his predicament with the snakes.

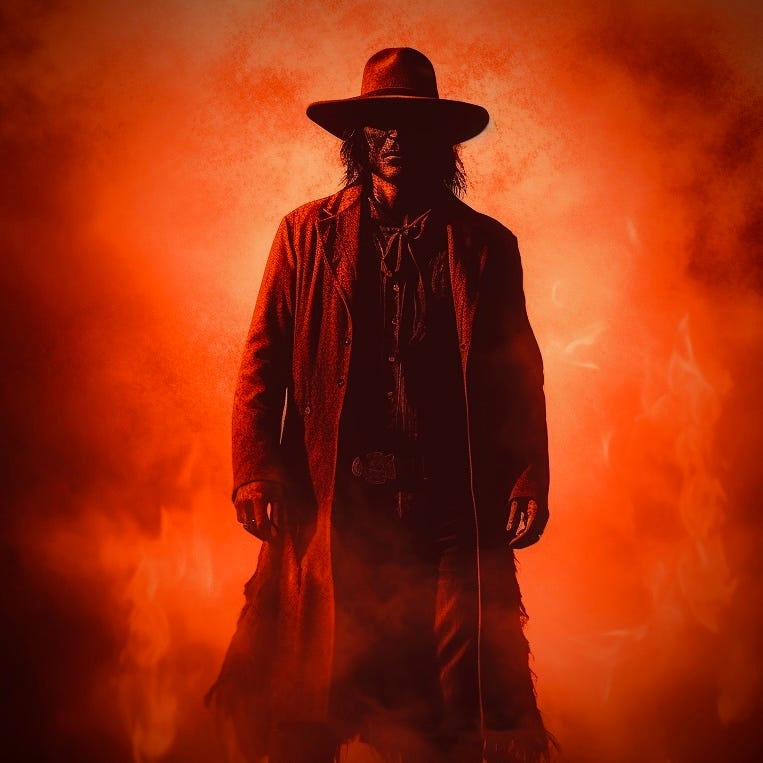

In front of him, an auburn-black mist unfolded, like the petals of a rose. Within it stood a shadowy figure that became distinct, though its countenance remained shaded beneath the broad brim of a cowboy hat. Evan didn’t need to see the eyes to know they were boring into him.

It would be nice if you’d help, he thought. And he hoped the figure heard his thought.

Ever since this elaborate dream had kicked off, it had been driven into Evan’s skull that auburn-black was the color of ‘prophecy’ and ‘truth’, so whenever it appeared in the dream he knew he was supposed to pay attention because something important was either about to happen or already had.

But Evan was synesthetic—though he didn’t know what that word meant—and had dreamt in color ever since he was a child; and (in his mind) auburn-black had always been associated with ‘doubt’ and ‘uncertainty’, so much so that, whenever he saw this color (whether awake or asleep), he tended to become skeptical and would say things like “I’ll need to get back to you on that” in an effort to prevent himself from being taken in and coerced by all the bullshitters and flimflam men, who were as common in his dreams as they were in his waking state.

A voice spoke out of the auburn-black mist in Hebrew, saying: Ma le-ka poh? (“Why are you here?”)

Evan ignored the question and lowered his gaze, smiling crookedly at the snakes. “I know who you are. You’re the Havasupai man, who runs the gas station on the Astral Plane.”

“I’ve been known by many names. But in this place and at this time, you shall address me as Master Yama, Lord of Death.”

Then both Evan and Master Yama simultaneously uttered the Sanskrit mantra: Om sahana vavatu. (“In peace let us proceed with our lesson”)

“You asked what I am doing here, Master Yama—”

“No, I did not. I don’t give a shit what you’re doing here. That’s an inaccurate translation of a profound and significant question that has been asked in one form or another ever since seekers first put pen to paper. . . Look into your atman, which is to say your self, and search for that which precedes all action, all doing, all verbs.”

Evan closed his eyes and saw a thumb-sized simulacrum of himself sitting in the lotus position inside a jeweled sphere. The figure was lapped in a pink-white-indigo flame, like those cheap-ass tie-dyed shirts Levi favored. Evan knew that this tiny (and admittedly handsome) man, his itty-bitty atman, was meditating inside the rib cage of his astral form, in that empty place where his heart had been.

“And so I ask you again,” said Master Yama. “Why are you here?”

“I climbed a tree,” Evan said, vaguely. “It’s hard to explain. I was climbing up and then I had to climb down. And now I’m in this tower and unable to move because of these snakes.”

“The uninitiated call this place the Tower of the Tumtum Tree. But there’s no such thing as a Tumtum tree. This tower houses the Ashvattha tree, whose roots grow upward and whose branches grow downward. It is the Tree of Life. Its roots draw nourishment from Heaven, while its branches, symbolizing Earth’s fruitfulness and rich diversity, touch the ground.”

“Ah. . . That makes sense. That’s why the part hanging down in the library looked like a twisted root. Like a snake.” And when Evan said the word “snake”, the serpents tightened around his chest, making it difficult for him to breathe. But the thumb-sized atman in his chest continued respiring in a state of unruffled serenity.

Evan decided not to dwell on the theological implications of the tree’s topmost root extending into that quasi-mystical library in the Canadian colony of Norway. Instead, he found himself asking a question that popped unbidden into his mind. “What is Brahman?”

Master Yama replied: “There was neither existence, nor non-existence; neither aether, nor vacuum; neither spatiotemporal extension, nor the forces of nature; neither an electromagnetic field, nor a quantum foam. There was not even so much as a ‘beyond’ from which such things could have sprung. What stirred it?”

“I dunno,” Evan said. “But I think about this stuff a lot.”

“Brahman precedes all action, all doing, all verbs. It permeates all that exists and all that does not. Brahman’s simplicity is concealed behind a multitude of seemingly discrete and individuated masks—masks that frighten, confuse and deceive, even as they soothe, console and delight. Etad vai tat.” (This, truly, is that, which you seek.)

Millions of light years away, the demoness Kaa-Manat stewed in the depths of her lair, devising a plan to disrupt this lesson and bewilder the master’s pupil. The dream-web, which Evan’s mind had spun, threatened her dominion over futurity. And if she failed to steal or obliterate it, then a new universe might be born.

With a flick of her scaly tail, she dredged up from the Well of Maya that lost memory that Madame Blavatsky had absconded with. It was the memory of the events that transpired in that honey-colored quadrant of Hell known as the land that was once called Kansas.

As the down-drifting dream-cloth fell (sidelong) into Evan’s mortal mind, he re-experienced that horrid Festival, where those grim apparitions had danced around a maypole in the presence of a wicker man in a cornfield. It was there that Evan’s sons and daughters were obliterated before his eyes.

When she had finished, Kaa-Manat withdrew into the folds of her snaky torso, and with her forked tongue licked the foul mephitic vapors of the Shattered City’s putrid cisterns.

Evan’s shoulders slumped when he saw again the headstones in the cornfields that marked the graves of his unborn sons and daughters.

“None of this is real,” he said in a hollow voice. “And since I now remember the Festival, it only goes to show that this entire dream, including those parts of it that I thought I’d forgotten, originated in my mind all along.”

In the jungle outside, Niyati, arrayed in a flaming red saree, looked up at the swift-rolling sepia clouds that converged on the tower from all directions.

Then she slowly began to fade away. “What is happening to me?” she asked.

The librarian frowned in dismay. “Your lover is losing the game. If he cannot believe in something greater than himself, then all is lost.”

Niyati looked at her transparent hands, and then again at the librarian.

“Why aren’t you disappearing as well?”

“Because,” the librarian said. “I never existed in the first place.”

High over the Pacific Ocean, aboard the flight to LAX, the astral form of Madame Blavatsky sat in the empty seat beside Evan’s vanishing body. The inert singularity that the boy had picked on the beach in Sydney now hovered before the Theosophist’s eyes.

“I can do no more,” she lamented.

The singularity dimmed and turned its non-existing head toward the other passengers in the cabin, all of whom began to disappear as well. Then the plane was invisible; and, beneath it, the white clouds of the planet Earth (where the sun rises in the west and sets in the east) began to fade away. And the stars winked out one by one.

“I believe in him,” Niyati said. “I have faith that he will succeed. He’s not as dumb as he pretends to be.”

The librarian looked at her sympathetically. Niyati squinted at the auburn-black light issuing from the upper level of the tower.

The black snakes constricted ever more tightly. “There’s something else I’ve been thinking about,” Evan remarked.

“What?”

“I know that even you are not real. I saw you in this role once before.”

The immortal Havasupai man, who had never known doubt, furrowed his brow and, as he did so, the auburn-black mist that enveloped him flared up until it became a blazing fire.

“You have never seen me before,” he said, though he spoke without conviction.

Evan ignored him and began to verbalize his train of reasoning to the delight of Kaa-Manat.

“I was nodding off on the couch one day. There was a cable documentary on about Aleister Crowley and the Golden Dawn. I’m pretty sure Madame Blavatsky was mentioned in it—along with ‘astral projections’ and whatnot. So that’s how all that crept into my head. The Dickensian librarian isn’t a complicated archetype for a person’s subconscious to conjure up. I knew Niyati as a boy, and met her again on the beach in Sydney shortly before I fell asleep on the plane.

“As for my apparent understanding of ancient languages, not to mention all those seemingly profound scientific insights I’ve been having at different points of this adventure, how do I know any of those are true? For all I know, my right brain has been babbling nonsense, and my left brain has been saying ‘yeah, man, that’s deep’ in the hopes that my right brain will shut up. Because the fact of the matter is, I’m pretty dumb when I’m awake. But I also know that my mind is fond of hoodwinking my sleeping ‘self’—my atman (if that’s the word we’re using now)—into thinking it knows more than it does.”

He paused to take a breath. And the canned laughter laughed. Evan laughed too and bobbed his head in acknowledgement: “I watch sitcoms even while doing my homework for background noise So that’s why canned laughter keeps popping up in the dream. . . Levi is my roommate; Marcus is my friend. But as for you and as Gordon. . . Well, the two of you were a mystery to me until now.”

Evan looked defiantly into Master Yama’s flashing eyes. “It was the day after Niyati and her parents moved away. I was 7 and I thought the loss of my friend was significant. It rained that day, and I was grumpy and moping around. I went to the store with mom. She was driving us home and I was sitting in the front passenger seat. We stopped at a red light near the gas station by my house—”

“The gas station you speak of does not exist,” Master Yama observed quietly.

Evan knew that this was true, but kept talking: “There was a husky man with auburn-black hair standing beside a flower-power van. He was selling vegetables near the curb. And for a brief second, his mask fell away and I saw his pain and suffering. But then he looked at the gray clouds and smiled, because all at once he was at peace. He was grateful to be alive.

“And that was because you, Master Yama, Lord of Death, stood by him with your hand on his shoulder. You had given him the courage to go on. The light turned green, mom drove away. And when I saw you, I, too, was comforted. You made me realize that there were others in this world whose anguish and pain exceeded anything that I, at that tender age, could possibly have imagined . . .

“Anyway, at the time I assumed you were in charge of that gas station. So that’s why you have such a grandiose title in my dream. And the man selling vegetables on the curb, is the same person my imagination has transformed into Gordon, the merchant-farmer.”

There came the sound of a hissing Himalayan wind, and two monks from the city of Shambhala, each wearing a mask, appeared out of nowhere, holding a third mask between them. They lifted the third mask and, when they did, Evan (unmasked) saw himself as a 7-year-old boy riding in that car on that rainy, which was stopped at that intersection near his house in Pasadena.

Gordon and the Havasupai man stood on the other side of the passenger window, each clutching a shaman’s staff; and, although the window was rolled up, Evan, who could neither move nor turn his head away, listened as Gordon began to tell a story. And the light turned green and the car moved forward at the speed of light, which caused the hood of the car to stretch to an infinite horizon, while all motion inside the car came to a standstill. (“The Impossibility of Motion” had been the title of that paradoxical book, written—paradoxically—in every language in the universe which had never existed, nor ever would.)

“The Great Yogi Elijah,” Gordon began, “climbed to the summit of Mount Brahma, which is to say the summit of Horeb. He found a cave and lodged there. And the triple-faced god of Creation, even Brahma, spoke to Elijah, saying—”

“Ma le-ka poh?” the Havasupai man interjected.

“Why are you here?” Gordon repeated. “The sages claim that, in asking this question in this way, Brahma was chiding Elijah for his presumption in following in the footsteps of a Rishi far greater than he.”

The Havasupai man resumed the story: “And Elijah said, ‘They have cast down your altars and quenched the Holy Agni. They have overturned the copper vessels and spilt the sacred ghee.’ — ‘Do I dwell in fire?’ Brahma replied. ‘Do I abide in the hilltop altars?’ Elijah was troubled in his heart and said: ‘They were established by your decree and ordinance. They are preserved and nurtured to your glory.’”

Here, Gordon picked up the thread: “Then Brahma confided to Elijah what he would one day reveal to the Rishi Hosea: ‘I desire lovingkindness (chesed), not sacrifices. I desire knowledge of Brahman, not burnt offerings.’”

—Now Evan stood beside Elijah beneath the overhang of the cave’s entrance. Together they regarded Brahma’s three faces, aligned vertically (one atop the other), like the apotropaic carvings of a totem pole. Each face was a persona (a mask) veiling the Godhead. But the masks of Brahma were now themselves vanishing behind a thickening bank of turbid clouds.

“Go forth,” Brahma said. “And stand upon the mountain before the Lord.”

Elijah and Evan emerged from the cave. Behind the cloud-bank, the lightning flashed and the thunder reverberated, but they kept their eyes on it, because they suspected Brahma was about to play a trick on them.

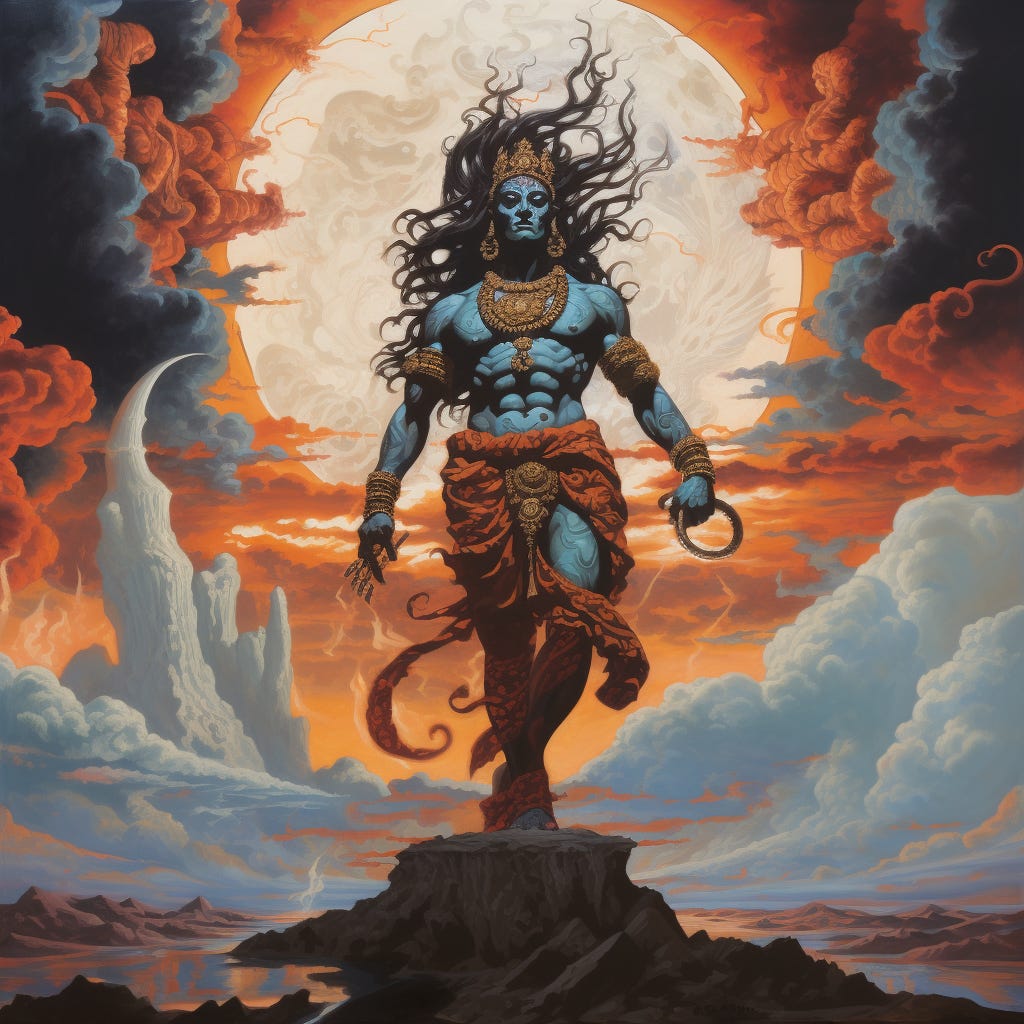

Suddenly, with gigantic steps, Indra, Lord of the Devas, stepped from the cloud-bank onto the desert floor. From his puffed-out cheeks, he blew a mighty wind that rent the mountains and broke in pieces the rocks. But Evan and Elijah kept their eyes on the cloud-bank, because they knew the Lord was not in the wind.

Then Indra stomped his feet, and when he did this, there came a roaring quake that split the earth. But the Lord was not in the earthquake. In his fury, Indra cast his thunderbolts until a raging fire scorched the desert sands. But the Lord was not in the fire.

Evan turned to Elijah. But Elijah kept his eyes transfixed on that roiling bank of turbid clouds.

Disappointed, Indra stooped to retrieve his spent thunderbolts. Then he strode away in humiliation, amid the whorls of dust and dying embers of his magic show. When he was gone, the cloud-bank parted. But Brahma the Creator was gone.

Gordon continued the story: “Then Elijah heard a still, small voice . . . ”

And the Havasupai man whispered in Hebrew: “Qo-wl de-ma-mah daq-qah.”

“It was the sacred Om,” Gordon commented. “The voice of Brahman. And when Elijah heard it, he covered his face in his mantle. For he knew he was in the presence of the divine.”

Then Evan heard—and saw—the Om. The syllable came to him dressed up in dapper diacritics (Ōṃ), complete with a smart hat and wingtips. This was the version he’d heard chanted from the towers of Shambhala. It appeared in the foggy window-panes of rain-lashed dachas, where it resolved itself into the Devanagari script: ओम्. Its vampire teeth clamped unseen onto the DNA of every living organism in the ligatured form of ॐ, which he recalled seeing on faded bumper-stickers around the UCLA campus. It was stamped on clay tablets and typed out in Braille (against a stippled background). And yet it was always unwritten, even in these written forms, because the Om was indistinguishable from the Logos, that soul-redeeming Word (with a capital “W”), which no unblessed vocal cord could reproduce, and which no unblessed ear could hear.

But Evan’s epiphany had only just begun. His synesthetic mind had invested the Om with a color below the infrared and above the ultraviolet. The smell of the Om was the stink of the grave intermingled with the pungency of myrrh and the fleeting aroma of unrequited love. The Om exuded a voluptuous tangibility, a furry sleaziness that wrapped itself around one’s organs, like a mink stole. Its taste was the acidic surface of scalding-hot ice-bergs that formed impossibly on the lava seas of unpeopled Hell-scapes dotted with quivering blue flames that cast no light.

All of these wild and illogical discrepancies were due to the fact that the Om—(at least in accordance with the mysterious laws undergirding Evan’s vivid dream)—represented the consummate union and harmonization of every discordancy and contradiction that theologians and philosophers had dreamt up since the beginning of (un)beginning time. Within the Om, all circles, including those Vedantic Saṃsāric ones, had been squared.

Evan stood beside Elijah on the brink of Horeb, as Gordon and the Havasupai man lingered by his car on the curb of that gas station in Pasadena at the four-way intersection near Evan’s home—(an unreal gas station on an unreal intersection in an unreal place called Pasadena in a universe that did not exist)—and the two shamans continued to narrate the story of Elijah to Evan’s 7-year-old self, as the light turned green and the hood of the car stretched to the vanishing point of that gray overcast day.

Then a voice spoke to Elijah, saying, ‘Why are you here’?

“Ma le-ka poh,” Evan repeated. And it finally dawned on him what the question meant. “Ohhh! Now I get it!” he said. “The voice was asking Elijah: Why do you exist?”

Evan closed his eyes, and when he opened them, Levi stood white-clad before him in the yellow twilight of a cornfield in that quadrant of Hell known as the land that was once called Kansas. The two friends stood at the base of Horeb, because gentle Levi had provided Elijah with food and drink before his ascent.

“Why have you never prayed?” Levi asked.

“Because I wouldn’t know who or what to pray to,” Evan said.

“That’s arrogance.”

“I know,” Evan said. Then his face became drained of all color, all expression, all emotion.

He looked “deep into himself,” and saw his atman meditating in his astral form’s rib cage, where his heart should have been. The atman grinned enigmatically as it opened its eyes and peered into that inner eye Evan was now using to look down on it. And, just as the car had paradoxically ceased to move upon achieving the speed of light, so too did something paradoxical happen to the atman’s expression, which suddenly darkened until it became cold and cruel.

But an inert singularity was lodged in the atman’s rib cage, which Evan’s inner eye had not noticed. And this inert singularity became ever more brilliant, as it grew smaller and smaller, until it became so miniscule that it encompassed the entire universe and transformed into the Purusha, that absolute and ultimate self-actualizing embodiment of Brahman.

Then Evan heard a distant chorus, chanting an ancient mantra over and over again:

Om Namah Shivaya

Om Namah Shivaya

Om Namah Shivaya The sound receded, and an entoptic spread of light appeared against his closed eyelids.

A die was cast, a playing piece moved, and 7-year-old Niyati said: “It’s your turn.”

He opened his eyes, and was relieved to discover that he was still asleep, still dreaming, still in the tower. But now it was he who was sitting on Lord Shiva’s throne. He was dressed as a Hindu warrior-king, and before him on the floor was a skeleton in a black kimono, bound with black ropes. It was his former self, and he saw now that in the darkness of his ignorance, he had mistaken the ropes for snakes.

He rose and stepped around the skeleton, because his attention had been drawn to a carving on the wall. It was a map, which looked just like the map he had carried with him from the train platform in Rajasthan. But in lieu of an X marking the spot he was searching for, there was a heart-shaped hole cut into the wall. Evan peered through it and saw beneath him (from the perspective of a Chinese watercolor) the Shattered City and a red pulsating glow.

At last! He had found his heart!

He turned around. The throne was gone, and in its place was the trunk of the Ashvattha tree, rising up through the tower’s roof. He climbed down the tree, through the central hole in the tower’s floors, until he reached the bottom.

When he saw the tangle of roots growing out of the tower’s flagstones, he wondered if that meant he was standing on the ceiling of Heaven. After all, the roots supposedly grow upward, he thought. He was surprised by how narrow the trunk was at the base. It felt much bigger when I was climbing it.

Then he heard Niyati’s voice, calling to him from outside. “Evan?! Evan?!”

“I’m in here!” he said, and sprinted through the arch that led out of the ancient tower.

When he was gone, the roots of the Ashvattha tree retreated (slitheringly) over the flagstones and retracted into the tree’s trunk. And as they did this, the same roots sprouted from the tree’s summit, climbing higher and higher into the fluffy white clouds until the topmost root corkscrewed its way downward through the rooftop of the undiscovered ruins of the university library in the Canadian colony of Norway.

Down it sank until it reached the crumbling spiral staircase and stopped. Madame Blavatsky looked at the root disinterestedly, and then closed and locked the door to the annex. She handed the key to the librarian, who accepted it and headed back toward the front desk, passing through the reading room beneath the painted ceiling depicting the Last Judgment and the Fall of Man.

The Emcee of the Astral Plane stood on the stage between the card catalogs, with one hand covering the microphone and the other cupped round his ear, because he was trying to hear on what Gordon and the Havasupai man, who stood huddled close together, were whispering to each other.

The two shamans were trying to figure out how it was that Evan could possibly have been present when the two of them had first met, since that encounter had taken place in a far-flung future that not even they were certain would ever come to fruition.

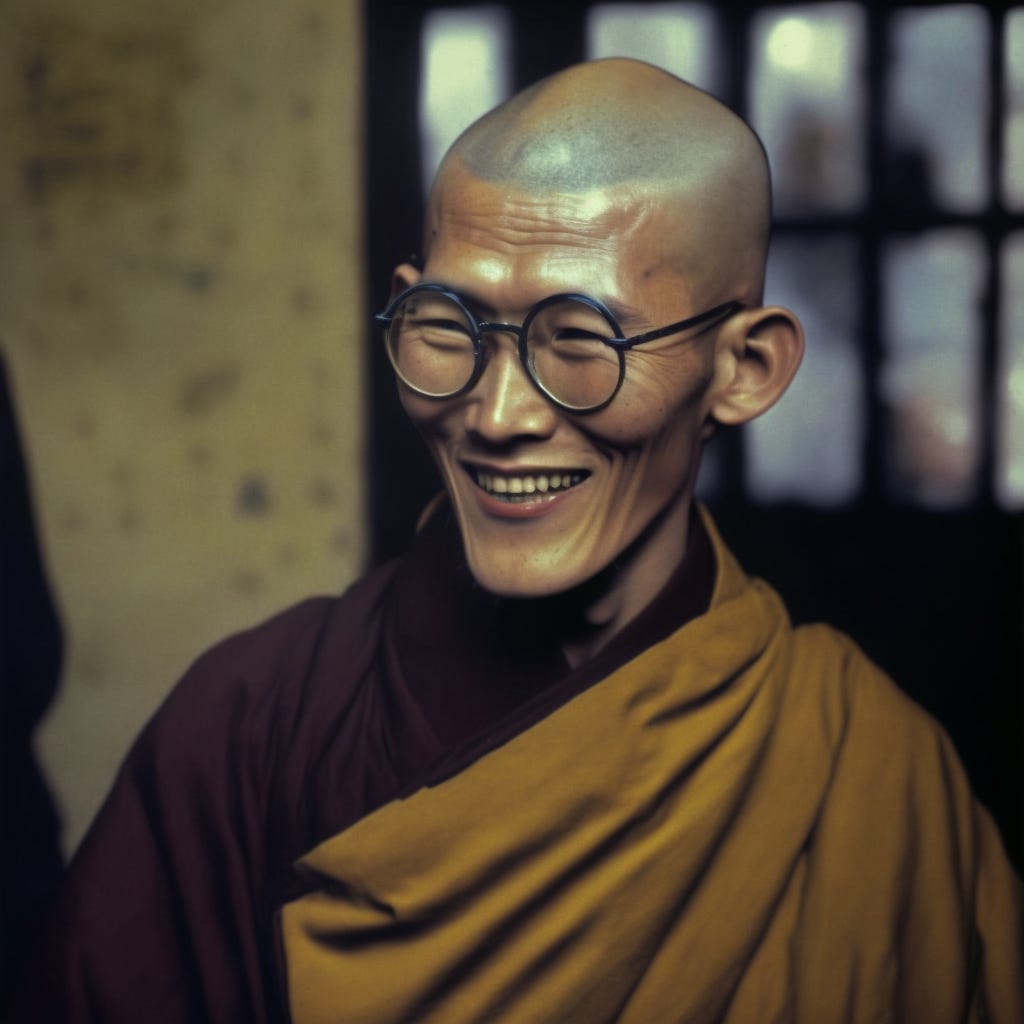

And as they spoke, the Khenpo, which is to say the Lord Abbot of the Holy City of Shambhala, emerged from the side-door of the Great Temple, and stood in that hissing Himalayan wind, laughing at the wise men’s perplexity.

Daniel, you may have defined creativity definitely in this chapter: ‘For all I know, my right brain has been babbling nonsense, and my left brain has been saying ‘yeah, man, that’s deep’ in the hopes that my right brain will shut up.’ 🙌🏻

As someone with no sense of smell, this struck me as especially apt: “The smell of the Om was the stink of the grave intermingled with the pungency of myrrh and the fleeting aroma of unrequited love.” Wow :-)