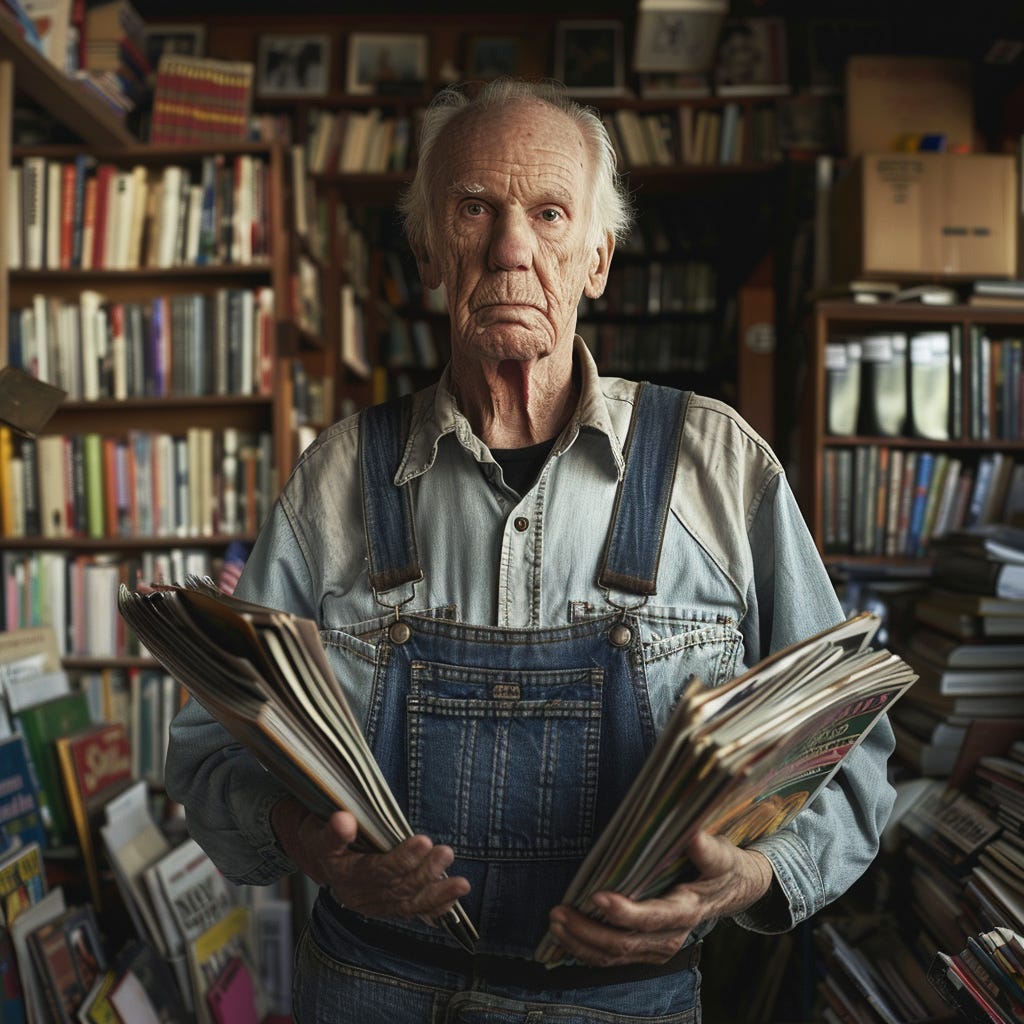

The Hoarder: Part 2

Part 1 | Part 2

Barry pondered the photograph of the shirtless man with the spotlight face staring up at him from the brittle page of the magazine. He wondered if “staring” was the appropriate verb to employ when describing an eyeless face: it certainly felt as if the illustration was contemplating him, even as he contemplated it.

Now that the initial shock of this revelation had worn off, the hackles on the back of his neck had lowered and he was no longer alarmed. The world was full of mysteries like these; and, if he’d learned anything in his nearly eight decades of living in it, it was that mother nature’s inflexible laws had a tendency to bend in rather unpredictable ways that made scientists sit back, scratch their heads and say “Hmm.”

The photograph was certainly at odds with the magazine’s purported subject matter (frontier history) and did not seem to comply with the standards of acceptability for mainstream publications of the late 1960s, a topic Barry considered himself an aficionado of.

The crackle of static in his headphones obfuscated the alien voice whispering to him from the beyond. From Barry’s point of view “the beyond,” “the afterlife,” and “outer space” (whether populated by ghosts, aliens, or fairies) were one and the same thing. It’s just easier that way, he would tell himself in those rare moments of philosophical introspection. All part of the same hallucination and whatnot.

He hit the “stop” button on his Walkman, removed the headphones, and was met by a silence in the motel room so absolute that it was more perplexing than the erstwhile moans of the copulating couple on the other side of the wall, who had quitted their dalliance and apparently forgone the muttering of post-coital endearments.

He strained his eyes to see if the illustration—or entire page—had been doctored or inserted by some rogue compositor who thought it would be funny. This did not seem to be the case. He played the tape recording again, but the voice beneath the hiss of static had gone silent. That settles it, he thought. I’m going back to Parowan to see if I can locate another copy of this magazine in my house to compare it to.

By the time he gathered up his belongings and loaded them into the truck it was nearly 10:00 p.m. He went to the front desk of the motor lodge where a bearded young man was on duty reading a sci-fi novel by the light of a sleazy red-shaded lamp.

Maybe I’ll leave my collection of magazines to him since he appreciates sci-fi. But he might not like other genres, so I’ll have to think about that.

He found a pad of stationery on a low coffee table with the motel’s logo on it. He made a grasping motion to the young man to indicate he needed a pen. The man pointed to a jar of ballpoint pens next to what looked like a laser blaster but was evidently a credit card machine.

Standing at the counter, Barry wrote out the following note:

I stayed here for a week and on the last night (tonight) my room smelled like pizza. But I don’t eat pizza (it’s not healthy, and if pizza stays out too long, mold grows on the cheese, and cheese is also a form of mold so it probably shouldn’t be eaten because mold can be toxic). Since I didn’t stay here the whole night (because of the pizza smell, I suppose), it would be fair for you to give me a prorated refund.

“Never seen a note like this,” the attendant said. “But I’m afraid I’m not authorized to give you a refund. You can check with the manager tomorrow morning when she gets in. I just work the night shift.”

Barry dashed off another note:

I have a 1962 sci-fi magazine with an original story by Isaac Asimov in it that only cost me $4.50. The story has only been re-anthologized twice since the author’s death. The magazine has a coupon clipped out of the penultimate page, but it’s otherwise in fair condition (corner of the cover is clipped off, though). If you give me the prorated refund, I’ll give you the magazine in return, even though the magazine is worth less than the refund should be.

“I told you, sir. I’m not authorized to give refunds. Sorry.”

Barry slammed his fist on the counter, turned away and walked out, throwing the key in the wooden box mounted to the door. That kid just lost an invaluable inheritance, Barry thought to himself.

He climbed into his truck, switched on the ignition and began the 235-mile crawl on the I-15 back to Parowan. If I can’t make it all the way, I’ll snooze at one of the gas stations south of Spanish Fork.

He kept to the right-hand lane to allow the speed demons pass. But there were not many travelers were on the road that night, other than the semis with their tangerine clearance lights and fussy air brakes bellowing out on the steep descents.

The solitude of the drive gave him time to think. He finally knew the mystery of why the cabin in the backyard had been built. Barry’s great-grandfather had erected it when the family staked their claim in Parowan so that his wife and brother could occupy it while the farmhouse was being constructed.

The disfigured uncle, whose relationship to Barry was technically that of a great-great-uncle—since his father had taught him that the brother of a great-grandfather was always a “great-great” uncle and not just a “great” one—had been named Grady. A lot of alliteration going on between “Grady” and all those “greats,” Barry mused. I wonder if the real reason they kept Great-Great-Uncle Grady in the cabin after the farmhouse was built was because they were ashamed to be around him, like mom and pop were ashamed of me, even though they said they weren’t. But I sometimes think they were. But maybe I’m wrong.

Great-Great-Uncle Grady (like Barry) had been a mute. How he hated that word—but not as much as dummy, which was what the kids (and even many adults) had called him when he was growing up. Barry presumed that it was the ghost of this ancient relative who had climbed into his bedroom window when he was nineteen years old, hugged him like they were the best of pals, and then had jabbed that needle into the base of his skull.

I guess Great-Great-Uncle Grady is the man with the spotlight face.

But there was a vexing aspect to all of this that he was having a difficult time wrapping his head around. What connection did Great-Great-Uncle Grady have to the aliens on the dark side of the moon who had been awakened when Apollo 11 landed there on July 20, 1969? And who was this great-aunt in San Francisco, who had aired the family’s dirty laundry before the author of that scandalous article?

Out of a sense of duty, Barry had preserved the family’s journals and photograph albums. He had perused these and would have remembered if pictures had been scratched out, or if a branches of the family trees had been intentionally lopped off. But there had been no mention in these private records of an estranged great-aunt or a disfigured great-great-uncle. And Barry’s father had been scrupulous about such matters.

He had to stop at three gas stations to fill his tank and empty his bladder. But he was so keyed up that he pressed on until he made it to the house sometime after midnight. As he pulled the truck up the rutted weedy drive, he realized that he would have to launch his investigation in the morning because his right hip and cogitative faculties needed a good night’s rest.

He slept soundly in his bedroom, the same one he’d slept in since he was a boy—the only differences being that the bed was bigger and the carpet couldn’t be seen for all the clutter. At one point he woke from a dream and peered out the window (from behind the tattered curtain) to ensure that Great-Great-Uncle Grady’s ghost was not in the cabin. All that confronted him across the yard was that open threshold, now as black as a knocked-out eyetooth. It was almost daybreak and the winking stars over Utah enameled the predawn sky.

But when he finally woke up it was late morning and he heard an unexpected ripple of thunder. Outside, all was now gray and misty. Inside, the walls of the rancid house groaned under the years of decay and neglect. It was not raining but Barry’s knees told him that there was a high probability that it would by midday.

Last night he had brought the perplexing magazine with him into the house; but because he had been so exhausted, he had left the other purchases in the bed of the truck (under the camper top). He would bring these in once the storm blew over. He didn’t want to risk getting them wet, although it was unwise to leave paper products in a space where damp could creep in. Even as he thought this, his gaze fell on a stack of magazines under a drafty window that hadn’t been caulked since his father’s death. The wall under the sill was mottled with mildew. The ink in the magazines had run together until the stack had been reduced to a liver-colored mound.

A mouse squeaked as it overturned an empty tin can near the kitchen door. That reminded him that he needed to buy trash bags. There were hundreds of empty cans stuffed in the pantry he needed to haul to the dump. The garbage collectors had stopped coming to the house because he refused to pay the exorbitant fee for their service.

In the half-light, Barry opened the magazine in question to the bookmarked page. The illustration was still there. He brought it with him upstairs, because he was fairly certain that, if he had another copy of it, it would be in the den where his father’s books on LDS history were shelved. Barry stored all of his nonfiction magazines dealing with pioneer history and the Wild West in this room because it felt like an homage to his father.

It was dark in the room so he switched on the overhead bulb to see by. He negotiated the narrow lanes between the stacked-up boxes as he began his search. By noon the clouds had thickened and the sky had become so dark that the dangling bulb in the den was no longer adequate to his needs. He went back downstairs and fetched a flashlight. After he returned, it took him less than an hour to find the box he had been looking for.

He was surprised to discover that he owned a complete set of From Desert to Deseret and that all the issues were arranged by the date of publication. He possessed three copies of the very issue he was looking for. One of them was in a transparent plastic sleeve with a price tag still on it (Vintage: $6.95).

He took the three copies and the one from Salt Lake City into the hall and sat on the hardwood floor. The reason he did this was to mitigate the risk of one of the teetering stacks in the den toppling over and crushing him. He removed the copy in the plastic sleeve first and opened it up. He held the flashlight in one hand and flipped through the pages until he came to the article. But to his surprise, the article was not there. He set the flashlight down and skimmed the other two editions. Again, nothing.

He grabbed the copy he bought in Salt Lake City and opened it to the bookmarked page. But both the article and the illustration had been magicked away; and, in lieu of the story showcasing Barry’s ancestors’ arrival in Parowan and the tragic tale of Great-Great-Uncle Grady, he found an article that he recalled having read years before concerning the history of Cove Fort and its pivotal role in the establishment of Utah’s first telegraphy lines.

Barry felt a sudden sharp pain at the back of his neck which then turned into a persistent dull throb. With some difficulty he stood up and bent over again to gather up all four magazines. Then he picked up the flashlight.

When he stepped back in the den to switch off the ceiling bulb, he saw what looked like a searchlight rake the dark sky outside the window. It was gone as quickly as it had appeared. He knew it wasn’t lightning by the way it had moved. His closest neighbor lived on a ridge two miles away. Someone must have driven up the drive. Perhaps it was the sheriff conducting another one of those annoying welfare checks.

Barry left all four magazines on the end table near the banister so that he could massage the back of his neck with his fingers. But he kept the flashlight in his free hand. When he reached the bottom step, quickly went to the front door and threw it open. There was no one in the drive.

He stood on the porch and saw that it was now peppering rain—and there it was again, that spotlight beam. It’s coming from the backyard where the cabin is. The contrast between the intensity of the shaft of light and the gloom of the drizzly afternoon was pronounced. He descended the steps of the front porch and walked around the perimeter of the building.

By the time he made it around the north side of the house, the rain “cut out” entirely. That was the only way he knew to describe it. Because he could see it was still raining on the horizon, but it was as if his property had suddenly fallen under a geodesic bubble.

He peered round the gutter’s rusty downspout at the corner of the house; and he saw what he thought he would see. The shirtless man with the spotlight face was standing at the threshold of the cabin. The figure craned its neck to face him. As it did that, the thunder rumbled overhead in a way Barry had never heard it do before. It was an infolding crackle that collapsed in upon itself and was re-expelled in a reverberative blast. He lifted his eyes and saw the underbelly of a massive triangular-shaped spacecraft rising up into a vaporous bank of black clouds.

His mind was unexpectedly exhilarated by the spectacle. But the rest of his body was reacting out of instinct and fear. This caused his hand to release its grip on the flashlight. His aged legs—since they too were apparently startled—ran back to the front of the house and up the porch steps. Once inside, his shaking hands slammed the door and bolted it shut.

All the while Barry’s cerebral cortex was sending messages to his reptilian brain, indicating that what was happening to him was the sole reason he had been “brought into gestation” in the first place; and that he should stop fighting against “us” because there was no longer anything to fear. But Barry could tell that his reptilian brain was calling bullshit on that because it had made him withdraw into his bedroom to get as far away from the front door as he could.

The curtains of the window over his bed were standing open and the man with the spotlight face was tapping on the glass. Barry felt his heart beating frenziedly, though his cerebral cortex still remained tranquil.

The shirtless man shattered the glass and climbed over the window sill. The edge’s of the creature’s torso—as well as what should have been the cloth of its trousers—sprouted glowing ciliated legs. The creature moved in a sleek writhing fashion, assuming the inhuman articulations of a gigantic centipede.

Even though his cerebral cortex was enamored with what was happening, his body his jaws opened in a voiceless cry. He tripped on something and fell backwards, landing on a collapsing mound of magazines. The monster rose up again and transmogrified into a semi-human torso. It wrapped its arms lovingly around Barry, fingers finding the nape of his neck. Suddenly, the needle that had been jabbed into the back of his skull when he was a young man was extracted from his brain, and a gaping wound was left in its place.

Barry felt hot blood oozing down his shoulder blades, but was aware of everything happening to him. He even knew that his mind and consciousness were now somehow encapsulated in the needle-like probe the alien held clenched between its slender fingers.

There were three things that struck Barry as quite hilarious in his final moments: first, was that this needle had been lodged in his brain for 76.55 percent of his life; second, was that there had never been a Great-Great-Uncle Grady; and third, was that the landing of Apollo 11 on the moon in 1969 had absolutely nothing to do with what was happening to him now. In his extremity, he gleefully conceived of a mixed metaphor to describe his predicament: My life has been a mackerel barrel full of red herrings.

He wished he could have shared this joke with the alien, but he suspected the creature was already reading his thoughts directly from the dripping red needle. Barry laughed so hard that he began to choke on his own blood. The creature executed a hideous pantomime of the dying man’s mirth, screeching like a bat and grabbing its belly as it swayed back and forth.

The old hoarder fell over; and his lifeless head landed on the cover of a fanzine devoted to James Whale’s 1933 film, The Invisible Man.

A month later the sheriff conducted a welfare check. There was no answer at the door, and the smell of decomposition, even from outside the house, was so overpowering that he called it in and was joined by a team of EMTs and law enforcement officials who entered the premises and discovered Barry’s decomposing body.

His death was ruled a homicide but was left unresolved. No motive or weapon could be found. The condition of the house was such that the county commissioner ordered it demolished. The magazines were dumped in a landfill; but the cabin at the back of the property was left intact (as a historical monument). A sign was erected at the front of the driveway indicating that the land was private property and that trespassers would be prosecuted.

After that, the estate began its long legal journey through the various courts.

But in mid-December 2023, the owner of the house on the ridge two miles away contacted the sheriff in Parowan to claim that someone was squatting on the old hoarder’s property because a “spotlight beam” (as the man called it) could be seen from time to time issuing from that old ruined cabin. On the day the sheriff’s office received the tip, Deputy Gabe Guzman headed over to check the matter out shortly after sundown.

On arrival, Gabe, who was 50 percent Samoan and 50 percent Mexican, instantly became 100 percent pissed off because his patrol car’s right tire got popped as he pulled up the main drive. It was 5:55 p.m. and this was to have been his last call for the night.

He cut the engine, stepped out, and turned on his flashlight to survey the damage. The wheel had been punctured (irony of ironies) by a rusty tire iron buried in the frozen dirt. Gabe had all the equipment he needed to change the tire himself, but it would take him about an hour to repair it. I can claim overtime for it, he thought. Little extra spending money for Christmas won’t hurt. But first thing’s first.

The house had been entirely leveled. Gabe shined the flashlight on the foundation stones and then lifted the beam to illuminate the cabin. He started trudging through the snow toward it. If smugglers or squatters were using it—and he really didn’t think they were—they would have been alerted to his approach up the long gravel road, since trees were sparse in this area, although there were frequent patches of wild grass, now webbed in white frost reflecting the glances of the winter moon.

He heard a clicking sound, almost like a crow clucking. It came from inside the cabin. Gabe was a big guy and not easily startled but he stopped in his tracks when a shirtless young man appeared suddenly at the threshold, skin blue from the cold. He wore pants and looked as though he was either a teenager or in his early twenties. But Gabe knew right away there was something off with the boy.

“Hey, buddy, you okay?” he asked. “Can you talk?”

The boy didn’t answer.

That’s when things got really strange.

The first thing he noticed was that the boy’s eyes didn’t move. They didn’t even appear real. They were like painted marbles in the sockets; and they looked off to nowhere. Yet under the eyes, there were pink protuberances moving on their own accord, as if they were concealing a second set of eyes. It made Gabe wonder if some insect or parasite had bored into the boy’s flesh and buried eggs under his lower eyelids. Twice the protuberances seemed to glow, but Gabe suspected this had only been a trick of his flashlight beam, which he was politely pointing down and away from the kid.

“Are you out here by yourself?”

Still no response. Then another peculiar thing happened. As Gabe spoke, his breath had fogged the air. As if only realizing that his own breath should have done the same, the boy’s mouth emitted a similar fog, even though his chest had been rising and falling as though he had been breathing all along.

“I don’t know how you got out here, buddy. But you’re gonna catch your death from pneumonia.”

Gabe raised one hand and stepped forward to let the boy know he meant no harm. He trained the flashlight into the cabin. The rotting floor was covered with a thin blanket of snow, out of which sprouted white polyps resembling grocery store mushrooms. A pulsating glow throbbed inside of them.

“What the hell is that?” Gabe whispered in awe. Then his beam fell on a network of membranous fibers and veins running from the colony of fungi on the floor up to the base of the boy’s skull.

“You’re coming with me.”

No sooner had he said this than the boy took off. The veins snapped from the base of his skull and a primal howl rang out. The figure moved at a velocity Gabe had never seen any man run. All he could see was the boy’s back and elbows, but an intense spotlight beam was shooting out in front of him as if he wore a headlamp.

“Come back here!” Gabe shouted.

Fearing someone or something else might have been hiding in the cabin, Gabe again swept the interior with his flashlight. The fungal colony and the veins that had snapped from the boy’s skull were still on the ground but had transformed into inert brittle shapes of ice.

When he again shined the beam in the direction the boy had run off to, Gabe saw no footprints in the snow. But far in the distance, over two miles away, he discerned in the clear night air a shadowy figure with a spotlight face standing midway up a rocky ridge, scanning the valley below. The light in the face dimmed but did not go out.

The figure slunk backwards until it stood flush against the mountain’s wall. Out of its torso spread what looked like a multitude of arms. Then it seemed to scale the vertical rock without once turning its glowing face away from Gabe. When it reached the top of the wall it disappeared over the ridge’s peak, leaving the deputy gasping in horror. I’m gonna fix my flat, he thought. Then I’m gonna drive home. Tomorrow I’ll tell the sheriff no one’s squatting in the old hoarder’s cabin. And then, come Christmas Day I’m gonna forget that I saw everything that I just saw.

Perfect. From the moody narrative to that filmic last scene, everything about this is horror gold. I love this, Daniel. Just sorry it took me this long to get here.

the image of the centipede creature climbing the mountain will haunt me forever