The Werewolf of Mariahilf am Inn II.21

A Gothic Horror Story

Book II, Chapter 21: The Transformation

List of Chapters | Previous Chapter

The slanting wisps of snow-fog drifted over a white field backlit by the rising sun, like a train of phantom monks filing to the oratory to usher in the winter dawn. It was the hour when Hermann as a boy had been accustomed to climb out of bed and join Papa and Oma Ingrid at the hearth to link hands and pray Lauds.

Benedikt concluded the first half of his tale concerning the funeral of the werewolf. As if soothed by the narrator’s voice, the drays he and Hermann sat upon stood stock-still, snuffling the icy air. In the middle distance, a lantern swung back and forth at the edge of the highway before floating out of the periphery of their contracted field of vision.

Hermann cleared his throat. “Probably a farmer checking on the snow at the head of the drive.”

“Perhaps,” Benedikt said glibly. “Or an Irrlicht (will-o’-the-wisp).”

“Not funny,” Hermann sulked.

The ostler spat in the snow and resumed his story.

“Fr. Matteo and the Italian retainers remained in that village hidden away in the Brenner Pass for a month. Nothing unusual transpired until the eve before their departure when one of the retainers got so merry with drink that he tripped on the door-stone of the taverna and cracked his head wide open. The men discussed the death of their companion with more irritability than compassion.

“They reasoned that the best course for them to take would be to ask the village priest if they could deposit his body in the so-called Rotting Tower and collect it on their return from Austria, since the hearse would be empty by that time. The priest acceded to their request.

“The wizened beldam who kept the stronghold’s keys led the men up the worn steps to the edifice. Once inside, they climbed the spiral staircase of the donjon. The windows of the ample room at the top were grated with iron to keep the kites out.

“The men snickered at their predicament. For here they were dropping off one body only to collect another. But to their surprise the body of Frater Melchior showed few signs of corruption. The eyelids were open and a gray batter pooled in the lifeless sockets. But the thin air had mummified the corpse, still wrapped in chains as they had left it. The old woman looked perplexed but said this sometimes happened in the cool months.

“But it was summer, unseasonably warm, and the floor of the tower was a living carpet of carrion worms and insects, which should have feasted richly on the meat of the carcass, since the bodies of the family of four on the flagstones nearby had been reduced to brown bones. Yet no creeping thing approached the dead Jesuit, whose dry flesh exuded an odor of musk and camphor.

“The retainers’ leaders hailed this as a sign from God, who, in His infinite mercy, had absolved the holy man of whatever unspoken—or unspeakable—sins he had committed in life. They freed the corpse of the weighty chains and fetters and lifted it from the slab, placing it on a white shroud and bearing it in this manner from the tower.

“The members of the party who had stayed below had been toiling away, reattaching the wheels to the funeral conveyance so that they could drag it out of the village through the mountain pass. The leader thanked the villagers and the priest for their kindness and hospitality over that memorable month. And with that, they departed.

“Fr. Matteo (my master) led the way, moving his lips silently and telling the beads of his rosary, as if absorbed in private meditation. The werewolf’s spell had waned with its death and the young Franciscan had awakened, as if from the fumes of intoxication, to the gravity of his situation. He regretted his decision to organize and lead this ghastly cortege—a decision he believed he had not made of his own free accord.

“By dusk on that first day, one the hearse’s wheels had cracked, making the other three useless. Despite the wood’s dearness, the men jettisoned all four and detached the reinforced poles mounted to the sides of the hearse so that it could be reconverted into a litter.

“As the days passed, a poet among the crew came up with a cadenced verse to help keep time as they marched on the dirt and gravel path. It was a song that gave voice to the superstitious belief among these simpletons that the cracking of the wheel had been an ill omen. The litter-bearers began to complain that they could feel the corpse ‘fidgeting about’ on the other side of the curtain.

“Their leader told them that, now that they were no longer carrying the iron chains or the heavy wheels, the burden they bore was much more lightsome than the one they had borne out of Rome. As a result, the litter-bearers were pushing and pulling against one another, which was causing them to imagine something jostling about inside.

“Whenever the men bedded down for the night, they spoke to one another over the campfire about the eerie dreams they had had, whose import they could not fathom. Fr. Matteo tried to allay their fears, even as he suppressed his own. For his dreams, too, had become hag-ridden; and he also heard something moving in the hearse.

“They emerged from the Brenner Pass and followed a canyon that wends its way through the mountains until it comes to that picturesque overlook above the valley of Mariahilf on the river Inn. On a grassy bluff in the foreground they espied the bell-tower of the chapel of Our Lady of Mercy rising like a beacon out of the gathering mist. The sun sank behind the western peaks and the weary travelers kindled a few torches and collected in front of the hearse to discuss how to proceed.

“‘The day is far spent,’ Fr. Matteo said. ‘If we descend into the valley tonight with this contraption draped in black, the villagers may suspect us to be banditti plotting some ruse. I recommend that we abide here till dawn, at which time I shall go down alone and search for the village priest to explain why we have come. After all, I am the only one of our company who speaks German.’ The men nodded in weary agreement.”

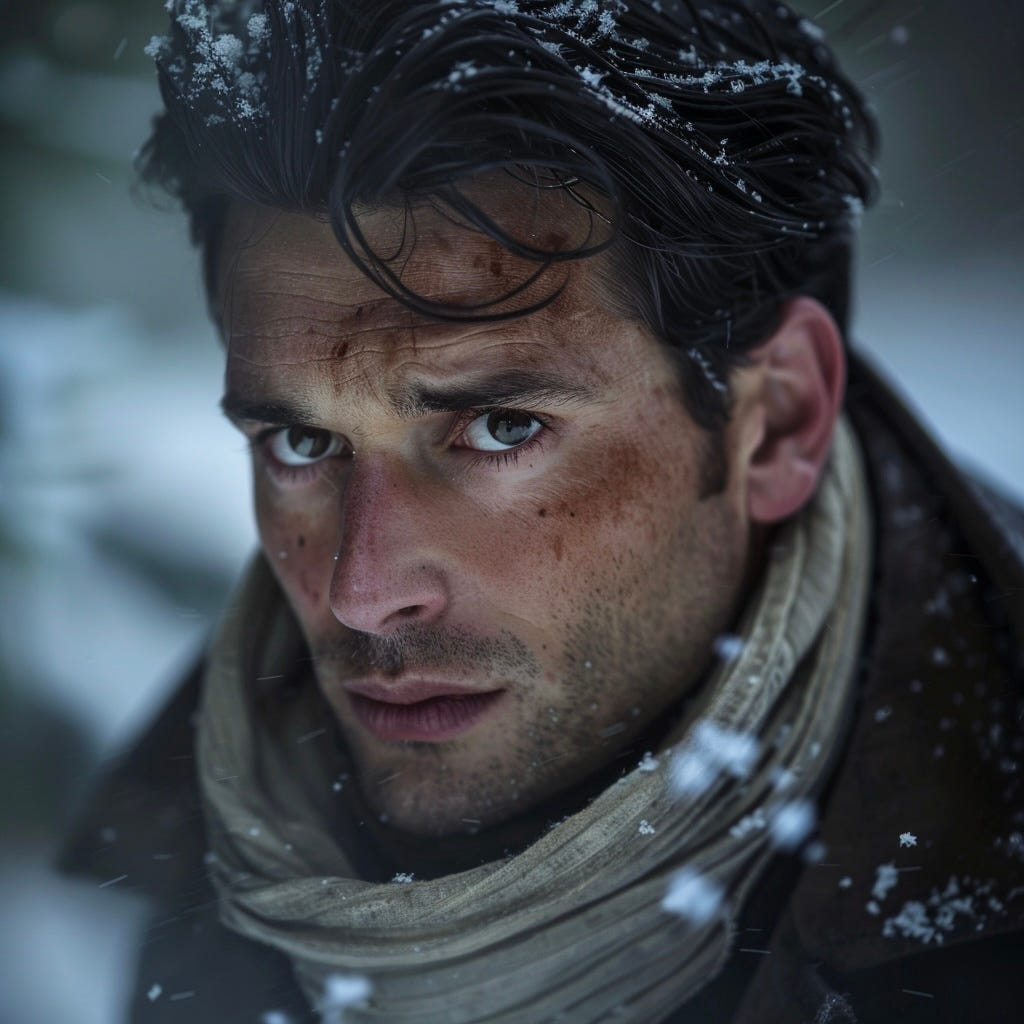

Benedikt drew in a deep breath. The ostler’s scarf had fallen away; and, in the half-light, Hermann saw that he was frowning.

“What’s wrong?” he asked.

“The place they chose as their halt for the night was the clearing where a boulder teeters over the brink—the clearing where you first encountered the werewolf and where I, as a young man, set eyes upon the murdered mother and her dead brood.”

“My God!” Hermann exclaimed.

“The men placed the hearse on a level karsk abutment and built a small fire, dousing all but two torches so that the villagers would not think a large group was encamping on the heights. Watches were set (four men to each) in the event someone hiked up to investigate. The men were ordered to wake Fr. Matteo immediately if this happened, so that he could communicate with them ‘in tedesco’ (in German).

“While this was being done, Fr. Matteo’s attention was drawn to the boulder. He recognized it from the story the werewolf had related to him (partially through a process of thought-transference) during those long nights the two of them had huddled tête-à-tête in the dungeon beneath the catacombs of Santa Maria della Concerzione dei Cappucini.

“The young friar climbed the boulder to see if he could pinpoint the iron rings hammered into the rock through which ropes had once run. The last rays of the setting sun struck the west face of the cliff and he saw beneath him two of those ledges that formed a discontinuous way that skirted the sheer rock and led round the bend to the hideout of the persecuted Waldensians. But it was too dark for him to discern any of the rings.

“The contumacious leader of the retainers scolded Fr. Matteo for putting himself in such danger. He demanded he get down, since, were he to plummet to his death, they might not be paid their due on returning to Rome. Meekly, the friar complied.

“As the men settled down for the night, Fr. Matteo lay in the shadow of the boulder and used a smooth stone as a pillow. It did not take him long to fall asleep. He dreamed he saw a dark-haired lady reclining next to him, naked, nursing four babes whose throats had been slit. But though dead, the lips of each child sucked one of the four tits dangling beneath her hairy chest. She grinned at him, as blood oozed from a gaping wound at her own throat. And when she opened her mouth to scream, Fr. Matteo opened his eyes and sat up, because a wolf was howling in the night.

“Amidst that lupine cry, the watchmen ran hither and thither through the camp, shaking everyone awake. They pointed at the litter and whispered tremulously to one another, because the black curtains were billowing out and being sucked back in with a bellows-like regularity, as if the lungs of an Amalekite respired within.

“The front of the litter was adorned with a crucifix whose base was sunk into the bed and whose upright rood was transfixed to a partition behind the curtain to keep it erect. The hearse was designed in such a way that the part of the corpse closest to the cross was the head. The most practicable way to peer inside was through the gap at the back, where a tall wooden statue carved to resemble a shrouded skeleton stood before the laced edges of the curtain.

“Fr. Matteo approached the rear, as the retainers whimpered and wrung their hands. A few crossed themselves, others gibbered inarticulately in Italian. Their leader held a lantern in one hand and, with his free hand, loosed the ties. Then he seized the flap and pulled it aside. With a deep intake of breath, he turned his astonished face to the young Franciscan, who gulped and looked inside.

“Swathed in the winding sheet, the werewolf of Mariahilf am Inn sat up on the bier, its eyes not only reflecting the lantern’s light but intensifying it. The creature wheezed; and with each exhalation, a luminous fog rolled out of the cracked, blue lips.

“Fr. Matteo shouted in Latin at the top of his lungs. ‘What is your name?! Who is your God?!’

“The monster’s enigmatic reply neatly answered both questions in a single breath. ‘My King is the light; my God is an oath.’

“Hermann, do you recall when I drunkenly confided to you that your mother’s name (Ilse) is a contracted form of Elizabeth, which in Hebrew means ‘my God is an oath’? Know that the name Melchior, also of Hebrew derivation, translates roughly to ‘my King is the light’. . .

“Now the thing spoke in a babel of tongues. It addressed the retainers individually, and in Italian, mimicking the voices of their loved ones, both living and dead. It was too much for them to bear. One by one, the retainers and their leader fled from the camp, abandoning their equipage, but taking with them a few lanterns and brands already lit so they could find their way back to the Brenner Pass.

“When they had gone, the demon turned its attention to the trembling friar. By the hellish light that suffused the rancid, thickening fog, Fr. Matteo stood paralyzed before this vessel of Satan, which now spoke to him. ‘By bringing me back to my home, Matteo of Trieste, you have cursed this valley forever.’

“And with that, the transformation began.

“The cadaver’s hair lengthened as the head attenuated and metamorphosed into the tail of a wolf. The mouth became a laughing anus that slid behind the shoulders, which cracked and unlimbered into the furry hind legs of something now tapping its claws. The knees of the corpse parted; and, as the death shroud fell away, the massive purple phallus transmogrified into a licking tongue that retracted into the groin, which was rapidly melting into a vagina lined with canine teeth—a phenomenon the exorcists of yore referred to as the cunnus dentatus, which is to say the fanged cunt of the Evil One.

“Up reared the muzzle of the beast, which extended through the gap in the black curtain until it hovered within a hand’s span of the petrified friar, who, in a swoon, fainted straight away.

“Someone shook Fr. Matteo awake. A bearded man crouched next to him preferred a flask of wine. It was morning. He sat up and pushed the wine away, examining his surroundings. A burly man in a black cassock stood close by. He addressed Fr. Matteo in Latin: Salve, Frater, quid agis (Good morning, brother, how are you)?

“The woozy Franciscan replied in German and the priest seemed relieved that the young man he thought was an Italian could converse in his native language. The men from the village milled about the hearse. Some were standing before the crucifix and praying.

“‘We know why you are here,’ the priest said. ‘Your departure from Rome was not exactly a secret.’

“‘I see,’ Fr. Matteo said weakly, still in shock. He glanced over his shoulder at the gap in the curtain from which the monster’s snout had protruded.

“‘You must understand,’ the priest said, ‘that Frater Melchior von Mariahilf am Inn died under mysterious circumstances more than thirty years ago. The Archbishop of Salzburg rejects the claim that the relics in that hearse belong to him. There is a grave in the valley below commemorating this son of Mariahilf for the work he did in restoring the chapel of Our Mother of Mercy. But for reason that even I do not know it stands outside the boundary stones of the cemetery.’

“The priest went to the hearse and threw the flap aside. He clucked his tongue at what he saw. Fr. Matteo stood up and joined him. A white skeleton in a pristine burial shroud lay on the bier.

“The priest let the flap fall. ‘I will have the men carry this down into the valley while I discuss with the aldermen what is to be done with these remains. In the meantime, you shall be fed and sheltered until you are ready to continue on your way.’

“The priest cast his eyes over the chaos and disorder around the camp. ‘Where are the men who accompanied you?’

“‘I don’t know,’ Matteo lied. ‘Perhaps they were afraid of your men’s intentions.’

“There was a commotion, followed by an outburst of laughter. It came from the boulder where Fr. Matteo had fallen asleep.

“‘All my life,’ a man said. ‘I’ve heard the wolves crying. But I’ve never laid eyes on one in the valley till now.’

“Fr. Matteo broke through the men, so he could see what it was they were discussing. In front of the boulder lay the carcass of a nursing she-wolf and her four cubs, all of whose throats had been slit. . .”

Benedikt’s voice trailed off as he uttered this last sentence. A dozen men on horseback were on the horizon. Most were uniformed; some wore civilian clothing.

Hermann raised his hand to hail them; and a captain raised his by way of acknowledgment.

When they had drawn up, Benedikt spurred his horse forward. He removed several papers from his saddlebag.

“I have here a sworn affidavit from our employer, Herr Abner Eltzbacher, confirming that the victims of the attack stayed at his coach inn. He affirms in these pages that the four bankers from Lübeck were honorable guests, caused disturbances or rows, and discharged all their debts and financial obligations before leaving his property on the day they were murdered.”

The ostler handed the papers to the captain, who passed them to a bearded man in a stovepipe hat. The man held the sheaves close to his eyes, because he was nearsighted.

Hermann’s jaw went taut. The man scrutinizing the affidavit was the inspector from Kohlendorf who had waylaid him and Walter during their flight from the workhouse over two months prior.

Benedikt noticed traces of profound agitation in Hermann’s face and acted swiftly, sensing that there was ill blood between him and a member of the delegation. “Moritz, return to the coach inn and tell Herr Eltzbacher that the delegation has arrived.”

Hermann silently rode off.

The inspector squinted at the man galloping away. “I’m in charge of this investigation now,” he said. “Where is the Bürgermeister of Am Haus Löringhof? He briefed me on the matter shortly before Christmas.”

“Herr Schuster is waiting for us at the Meyer Farm,” Benedikt replied. “The coach, the mailbags, and the strongbox the men were carrying have all been moved there. Most of the money that the men had on them at the time of the massacre has been accounted for.”

At the mention of money, the inspector licked his greasy lips and thrust the affidavit into the folds of his mantle.

Benedikt flicked the reins of the horse and guided it into the adjacent field. “Follow me. I’ll be taking you past the place where the victims were found.”

That may be the most vivid nightmare I’ve ever encountered (including my own)! And the description of the mummy was gorgeously gruesome :-)

That’s some opening sentence, Daniel!