Book II, Chapter 20: Funeral of the Werewolf

List of Chapters | Previous Chapter

Benedikt could tell by the way Hermann’s eyes drooped over the closed notebook that the depressed man had finished reading the account of the werewolf’s origins. The ostler held Wellington by the reins. The “smoking out” of the stable’s pests and rodents was almost done. The fumes seeped out of the gaps between the planks and thinned as the fire subsided within. A shift in the direction of the winds carried the dusky billows over the field adjacent to the property.

The sinking winter sun glanced off the frosty stubble sticking out of the snow. Recalling his days as an itinerant schoolmaster, Benedikt was reminded of that Latin word Roman poets had used in their pastorals and eclogues to describe stubbly fields, stalks of corn, or the serried ranks of pikemen—horridus, from horrere: ‘to stand rigid or upright’, like the hairs of one horrified. He saw Hermann shudder involuntarily at the implications of the monster’s story. A story I too am involved in.

The ostler led the stallion back to the hitching post where Hermann waited, sullen and slump-shouldered. As he tethered Wellington to it, he hacked up a lung full of soot and spat it on the snow. “I’m sure you still have questions.”

“Yes,” Hermann whispered. “But thanks to this narrative, I also have answers.”

“As we agreed, we must destroy the manuscript.”

Hermann nodded and followed Benedikt to the double door of the stable. The ostler unlatched it. Each man opened a fold and thrust the flush bolt into the dirt. The outpouring smoke clung to the earth like the skirts of a witch’s gown. When a blast of wind invaded the interior and rattled the tools and equipment on the walls, the dying flames fanned up anew and sparks rose to the rafters. The two men coughed, as Benedikt (still wearing work gloves) grabbed the notebook from Hermann’s hand and flung it into the fire pit he’d dug in the middle of the dirt floor.

A feline hiss was heard from the stalls. And when they glanced that way, they espied Walter’s one-eyed cat, Mürrisch, couchant on the wet straw.

“How did it survive the smoke,” Benedikt snarled.

“It’s the Devil’s cat,” Hermann replied.

Suddenly, their attention was drawn to a cat meowing outside. They looked and saw Monika shooing Mürrisch from the inn’s backdoor with a broom.

“Florian,” she yelled. “If you want to keep the cat, he needs to stay in the coach house.”

“I’m sorry!” Walter replied, as the cat leaped into the orphan’s arms.

When Hermann and Benedikt turned around, the cat that they thought they had seen turned out to be a rotting coil of hempen rope. But they heard again a feline hiss, this time from the fire where the edges of the notebook curled up and were consumed in an uncanny green flame.

The massacre of the four bankers from Lübeck (along with their hapless coachman) on the highway south of Am Haus Löringhof became the subject of a gruesome comic opera performed at a vulgar music hall on the Reeperbahn in Hamburg. Since the victims’ private papers had not been stolen or damaged, each man had been buried under his confessional rite.

But two had been Jewish and their corpses had been laid out in the mill house for two nights as the aldermen discussed the crime and what was to be done. As a consequence of this, Bürgermeister Egon Schuster consulted with the village rabbi, who took it upon himself to oversee the ritual washing of the men’s corpses (the Tahara) and their dignified interment in the Jewish section of the village cemetery in the woods.

The horror of that night was still fresh in the minds of the citizens of Am Haus Löringhof; and it was at the forefront of the mind of Farmer Meyer, who had been asked to keep the very coach (still operational) that the men had died in locked up in his barn. The reason for this was that, even though the crime had been committed on a public highway, the dead men’s coach had rolled into his field.

As December passed into January, Farmer Meyer began to annoy his neighbors with repeated claims that on blustery nights masculine voices could be heard whimpering in his barn; and that his wife, while fetching water, had heard a man cry out, “Mein Gott, es ist ein Werwolf!” (My God, it is a werewolf)

There had been unconfirmed reports—as early as the opera singer’s visit to the Eltzbacher Coach Inn—that the war with France was coming to an end. Several coach firms had issued notices cancelling routes and had stopped sending replacement horses to certain coach inns out of concern that, if the Prussian soldiers were demobilized and crossed the border back into Confederation territory, they might be desperate or starving. Investors did not want their carriages stolen or their horses eaten for meat.

A message arrived at the Eltzbacher Coach Inn on New Year’s Day, 1871. Elischewa read it through twice. Then she sat down at her desk in the office beneath the staircase in the coach inn’s common room and composed a note of her own. She sealed it and directed Walter (whom she knew only as “Florian”) to deliver both messages to Herr Schuster in the village.

The original letter (on Hohenzollern letterhead) announced that a platoon of Prussian soldiers would be arriving from Kohlendorf on 4 January, escorting representatives from the Cronenberg coach firm, who would be arriving to reclaim the company’s property. The Prussian soldiers would take possession of the bankers’ personal effects, along with the strongbox of money they had brought with them. The bundles of mail, which the coach had been transporting from Hamburg (in its dual role as a packet), would be collected and forwarded to Cologne, where it had originally been destined.

In the supplementary note, Elischewa notified Herr Schuster that Hermann and Benedikt would rendezvous with the visitors on the road south of Am Haus Löringhof (in the vicinity of the Meyer farm). She did not want the Prussian soldiers to come to the inn out of fear that they might snoop out the premises and, when they had returned to their command, propose the Eltzbacher estate be seized by the military and converted into a hospital, barracks, or something equally dreadful. She reminded Herr Schuster that the mail bundles were already with the coach in the Meyers’ barn. She suggested that (as Bürgermeister) he should move the strongbox and money to the farm as well and lodge with the farmer and his family until the visitors had come and gone. Herr Schuster applauded the idea and promptly burned the note so that it could not be used as evidence against him or Elischewa at some future date.

Early on the morning of 4 January, Hermann and Benedikt walked into town to borrow two dray horses from the village brewer, since they were the only horses available—other than Wellington, who was getting on in years and would not have had the stamina for a task such as this.

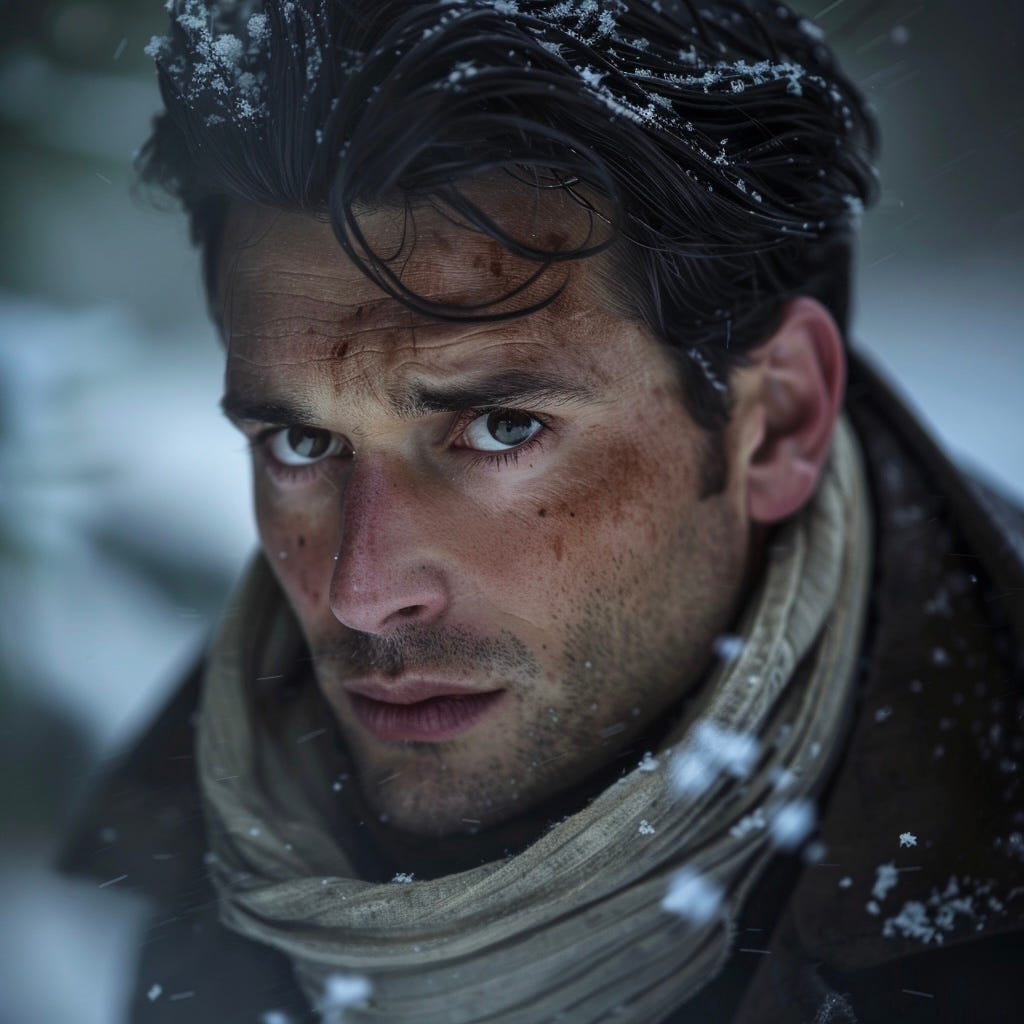

They took up a position in the middle of the icy highway. The sun had not yet risen, but the moon was bright. To save fuel, they doused their lanterns, and for nearly an hour sat on their saddles (in the dark), teeth chattering under their woolen caps. To keep from nodding off, Hermann pondered Benedikt’s narrative of the werewolf.

He thought of that pagan village outside of Wolfsberg in the Austrian province of Carinthia, the place where the wicked Frater Melchior had succumbed to the curse of the werewolf sometime in the summer of 1762. It now made sense to Hermann as to how the wretch had ended up in that cramped cell beneath the catacombs of the Capuchin church in Rome. Maria Theresa’s personal physician, Baron Gerard Van Swieten, had banished him from Austria. According to the final paragraphs of the manuscript, Frater Melchior had been wrapped in chains and sent to Rome “for the Pope to deal with.” But it was doubtful His Holiness had ever been informed of the matter.

Frater Melchior remained a prisoner in the catacombs for over thirty years. He did not utter a word. His body did neither aged nor decayed. He would only eat raw flesh and tripes; and, if deprived of such delicacies, would howl so volubly as to disrupt the singing of the canonical hours in the church high above.

The friars who tended to him had never been told why the cannibal had been brought to Santa Maria della Concerzione dei Cappucini. Over time they formed their own opinions. Some believed their undead charge was a demon; but others speculated that he would not have been brought to so sacred a place unless he were a saint.

Enter Benedikt’s erstwhile mentor—that false and effete medical student—who arrived mysteriously in Rome in the guise of a Franciscan friar and became the monster’s warder. He had intended to commit a grievous crime: the murder of his uncle and his uncle’s offspring, members of a cadet branch of the House Barberini. He had planned to do this in revenge for the death of his own father and family on the orders of the same uncle. It was like a Spanish tragedy that begins with a soliloquy and ends with a stage awash in pig’s blood.

Perhaps it was Matteo’s moral and spiritual frailty that had enabled the werewolf to worm his way into the young man’s confidence.

A panicked spasm racked Hermann’s body. He had almost fallen asleep. If he had done so, he might have tumbled off the horse, which was a rather embarrassing but all too common way to die or become permanently invalided.

It had stopped snowing. The stars in the east were dimming as the sun began its ascent. Hermann asked Benedikt to explain the connection between Fr. Matteo and the werewolf. “What was the nature of this relationship that had formed between the two?”

Benedikt welcomed this diversion, which had rallied him from his own lassitude and torpidity. Without preamble, he launched into his story. . .

“The monster refused to address my master by the honorific ‘Fra’, knowing full well that Matteo was an imposter. He had studied him closely on those long nights when the young man sat before his cell, hard at work grinding glass into powder which he aimed to slip into the cooking flour of his enemies. But the werewolf also had the ability to peer into Matteo’s mind. And so he knew that the young man’s tastes ran to the stronger sex and that Matteo’s male lover had been slain—”

“There’s no such thing,” Hermann grumbled.

“What?”

“There’s no such thing as a love of that kind between men.”

“Hermann, how can you be so naive?”

“I don’t like this Matteo character. And I don’t understand why you speak of him with tenderness and sympathy. He was a godless man. He almost led you to your death in that Waldensian cave. The Church authorities would be scandalized to learn that a man with such proclivities had infiltrated their ranks. . . Why are you laughing?”

“Do you want me to tell you the story or not?”

“Go on.”

“The werewolf recounted to my master everything that I wrote down for you in that notebook. He stated that his words were intended for ‘a little boy yet to be born’. That being you, of course. Having unburdened his soul by this confession, he claimed that he was at last ready to die. But he would need Matteo’s assistance to accomplish this.

“‘How so?’ Fr. Matteo asked.

“The prisoner’s visage became sly. The young man was ignorant that he had been enthralled and fascinated by the Evil One.

“‘The glass that you have pulverized, and that you have concealed here in the catacombs. . . You intended to use it for a dark purpose for which you have since repented. Bring it to me.’

“Matteo did as the creature bade, retrieving the jar. Through the bars he poured the powdered glass into the prisoner’s cupped hands. The werewolf swallowed it greedily, and pointed to the second jar. When that too had been depleted, he licked the residue on his fingers as if it were the sweetest honey.

“‘Mmmm,’ he said, as the blood trickled down his lips and collected in his beard. ‘The only thing tastier than glass is the blood of the righteous and innocent.’

“My master later admitted to me that, at this point, the spell that the monster had cast upon him nearly broke. Seeing the Matteo’s perplexity, the creature’s visage morphed again into an expression of seraphic tenderness. He slumped to his knees as if only then feeling the fatal effects of what he had consumed.

“‘I wish to be laid to rest,’ he said, ‘in the Tyrolean valley where I was born. Please, Matteo, take me back to Mariahilf am Inn.’ He collapsed and could no longer speak (but neither he could he die).

“Fr. Matteo fled the catacombs and returned minutes later accompanied by the abbot, the prior and several lay brothers of the Capuchin Order.

“Without mentioning the shaved glass, Matteo quoted a false confession that the prisoner had ostensibly made, adding that the man had claimed that he was dying; and, while he had still been able to speak, had begged to be taken back to his home. At this point, Matteo repeated the name and location of that remote Austrian village. And as he spoke, the werewolf reached through the bars and clutched the prior’s habit, nodding in pained agreement with the fabulous tale the bewitched youth was recounting.

“When he had finished, the abbot revealed that the prisoner once, long ago, had been a Jesuit priest, as well as an accomplished artist from the very place that Fr. Matteo had just mentioned. Although not unsympathetic to the dying prisoner’s wishes, the abbot explained that the church did not have the resources or means to fulfill the man’s request.

“‘If I were to find a way,’ Matteo said (as the werewolf mouthed the words that he spoke). ‘Will you permit me to take him back to Austria?’

“After conferring with the prior, the abbot gave his consent. Leaving the church, Matteo bent his steps to the Palazzo Barberini. He pounded on the outer door of the complex where his uncle lived. When the servant answered, he asked to speak with Signor Ludovico.

“When the nobleman appeared at the threshold, he recognized the young friar who had shriven him and saved his mortal life, though not his immortal soul. Matteo reminded him of that significant encounter and requested a favor in return. . .

“The following morning twenty manservants wearing the colors and insignia of the House Barberini appeared before the church with a covered wagon, the wheels of which could be removed to convert it into a litter so that it could be borne through the mountainous terrain. The wheels were too small for beasts of burden to pull effectively. But men wearing chest-harnesses could drag it by ropes with relative ease (though not with speed).

“Because the prisoner was still alive, it was decided to keep him bound in chains as a precaution. He was brought up from the catacombs lying on a cot, which was placed in the wagon bed. The cart was covered with a white canopy, every side of which was hung with wooden crosses. A magnificently carved crucifix adorned the front; and a tall statue of a robed skeleton was mounted to the back, so that everyone who witnessed the cart passing would understand that the occupant was either dead or soon to be.

“Fr. Matteo led the way. It took them six weeks to reach the Brenner Pass, but Frater Melchior was still alive and hungered for raw flesh. The retainers had been well remunerated for the trip; and Ludovico Barberini had affirmed that their families would be taken care of for the duration of their absence. But they expressed their uneasiness at the fact that the man in the cart feasted only on blood, raw meat, and entrails, produced no waste, and frequently laughed and howled in the evenings.

“They departed Bolzano at sunrise; and, at sunset, reached a small hamlet located in a narrow mountain defile. The village no longer exists, having been razed to the ground shortly after Napoleon’s conquest of Italy in 1799.

“When Fr. Matteo checked on Frater Melchior’s condition, it appeared to him that the man was no longer breathing (though his eyes remained open). The young man climbed up into the cart and placed one hand over the marble-blue lips. He felt no breath on his palm. He laid one ear on the monster’s chest, but could hear no heartbeat.

“The village priest was summoned so that the situation could be related to him. The old man’s Italian was so thick with Tyrolean regionalisms that the Romans had difficulty following him. But Fr. Matteo, being from Trieste, reverted to the Venetian dialect of his youth; and the two were soon speaking familiarly with each other.

“The priest understood their dilemma. It would take them at least ten days to reach Mariahilf. The body would be stinking by that time. The priest pointed to a bleak medieval stronghold built high on a ridge. He indicated that the tower was perforated by windows open to the cool mountain air; but the apertures were closed with bars to prevent kites and other birds of prey from getting in. There were few rats at this altitude; but the stronghold was full of worms and carrion insects.

“The priest suggested transferring the corpse to the tower and leaving it there for a month to accelerate the process of decomposition. Fr. Matteo and his entourage would be fed and entertained by the villagers until the expiry of that term. This was how the locals disposed of their dead due to the lack of consecrated ground so high up in the mountains.

“‘We wait until the body has been entirely reduced to bones,’ the priest said. ‘Then we remove these to the charnel house located next to the church. The elevation of the stronghold generally keeps the vapors of decay from sinking to the dwellings below. We currently have a family of four in various stages of decomposition up there. I can’t guarantee that all the flesh will be eaten off your man within a month. But I can guarantee that you will be exiting the Brenner Pass with a much lighter and less noisome burden.’

“Fr. Matteo conferred with the retainers’ leader, who agreed that the priest’s proposal sounded logical. They accepted the villagers’ offer of hospitality and some of the men were already enamored by the blushing mountain maidens they saw at work.

“It was dark. Torches and lanterns were lit. Matteo followed the porters—and the old woman who kept the stronghold’s key—up the steps to the dank edifice. They ascended the tower’s spiral staircase and reached the top. The steps and warped floorboards were alive with worms and crepitating insects. The fetor was oppressive; and the men swooned. Some vomited; and one fainted straight away on seeing the cadavers of the family, lying pell-mell on the floor with their limbs askew. The old crone stood at the threshold, laughing and twirling the iron key on her index finger, as she confided to Fr. Matteo that she no longer had a sense of smell.

“Retching and covering their mouths, the porters took the cot to the corner of the room. The leader asked Fr. Matteo whether they should remove the chains or leave them.

“‘Leave them,’ Fr. Matteo said. ‘We’ll retrieve them when we come back for the body.’

I am psyched for the full book to come out.

It reminded me of the atmosphere of the movie Brotherhood of the Wolf. A great movie. Well done, Daniel!