Book II, Chapter 18: Frater Melchior von Mariahilf am Inn

List of Chapters | Previous Chapter

Benedikt exited the carriage house and bent his steps to the hitching post near the stable where Hermann was reading the manuscript.

“I’m only halfway through,” Hermann said apologetically. He was starting to feel rather intimidated by the vast stores of knowledge the mild-mannered ostler had squirreled away in his noggin.

“No need to hurry,” the curly-haired man replied, stomping his feet to free the tips of his boots from the clumps of snow. “I tried to nap but Walter’s damned cat kept yowling.” He removed his work gloves from his coat. “Have you found any of it difficult?”

“If by ‘difficult’ you mean its legibility, no. Your penmanship is impeccable. And you’ve parenthetically explained the things that are beyond my ken. But if by ‘difficult’ you mean the substance of the tale, then yes.”

The light of the December afternoon was in retreat; and the shadows cast by the carriage house and the gabled well stretched almost to the hitching post.

“I’m going to bring Vellington outside,” Benedikt said. (‘Wellington’ was the Eltzbachers’ elderly stallion, named after Abner’s hero, the English field marshal of Waterloo fame.) “I’ll tether him here to keep you company. I need to button up the stable and kindle a fire inside to smoke out the mice and vermin that have taken refuge there. When you’re finished reading, we’ll burn the notebook in the fire.”

When Wellington was tethered to the hitching post, Hermann gave the horse two turnips he fetched from the root cellar. He took care to keep the notebook away from stallion’s mouth. Wellington bobbed his head twice when he was done, satisfied by the snack. Hermann patted the horse on the neck and stepped out of the tether’s rang so the affectionate animal didn’t try to nuzzle up against him as he read.

History of the Werewolf of Mariahilf am Inn (continued)

On Ascension Day, 1739, the villagers of Mariahilf am Inn gathered breathlessly outside the renovated chapel on the bluff, waiting for the rededication ceremony taking place inside to conclude.

Beneath the chapel’s larch rafters, Father Holzer conversed with ten bearded faculty members from the Jesuit University of Ingolstadt. The men were clad in black coats with white ruffs at the collars. The stonemason and his son stood beside a Romanesque column. The delegates gawked at the Baroque mural depicting Our Lady of Mercy.

Melchior had never seen men dressed so foppishly. But then he and his father had been scrubbed up for the occasion as well.

The stonemason, who had never worn a hat, gripped a tricorn decorated with a red-and-white cockade (the Habsburg colors). Melchior’s hair had grown quite long since starting the mural, so the weaver’s wife braided it into a French queue and powdered his face with ratsbane. He wore a loose-sleeved tunic, a white cravat, silk stockings, and buff hosen. The ill-fitting pumps his feet had been crammed into were as tight as the glass slipper on the feet of Aschenputtel’s stepsisters.

Two delegates could not speak German (one being from Seville and the other from Annecy), so the assembly posed questions to Father Holzer in Latin. Suddenly, all eyes fell on Melchior. He looked away in embarrassment, gratified the powder had concealed the blood rushing to his cheeks.

He focused on the discoloration at the front of the altar, where the hole had been in which the werewolf medallion had been secreted—the cursed relic he had disposed of on the night he had slain the heretics in the mountain. They had deceived him into believing they were Christians, flattering him with their claims to have seen intimations (in dreams and visions) of his promising future.

Beware of false prophets, who come to you in the clothing of sheep but inwardly they are ravening wolves.

“Wolves, every one of them,” Melchior hissed. His father shushed him, assuming the comment had been directed at the Jesuits. This day would be the last time Melchior would ever see his Papa again.

Father Holzer notified the stonemason that the delegates were united in their belief that the painting was a miracle. They proposed taking the boy to Ingolstadt to be educated, and later inducted into the Society of Jesus. Though the stonemason’s countenance glowed with pride, he said the decision was up to his son. Melchior saw this as prove positive that his rooting out of the unholy coven in the mountain had been sanctified by God.

The boy went to the dean of faculty, knelt before him and kissed the signet ring on the gloved hand.

Though he arrived in Bavaria illiterate, his mind had somehow acquired a capacity for the rapid acquisition of languages. Within days of his matriculation, he was able to write German in a delicate slanting hand. His insatiable curiosity drew him to the marble corridors of the Society’s grammarians and casuists, who regarded the boy’s intellectual endowments with a mixture of wonder and fear.

By the winter of 1739 Melchior could write and speak Latin fluently. Not only could he read Holy writ and the most abstruse tracts of the Doctors of the Church, but in the evenings he pored over the writings of the Roman Architect Vitruvius; and lost himself in solitary reveries, pondering the mathematical diagrams of Euclid and Archimedes.

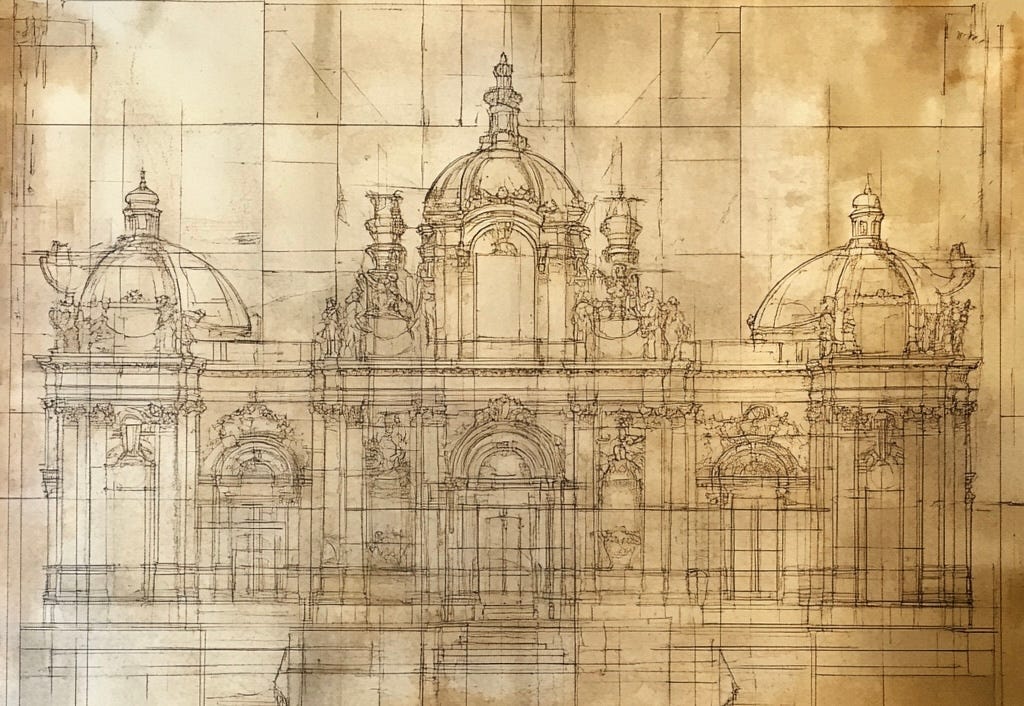

An elderly Jesuit who hailed from Cremona, whose responsibilities including overseeing all construction taking place at the university, taught Melchior enough Italian for him to read with comprehension the notebooks of Filippo Brunelleschi, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and the great Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci. Combining an innate sense of balance with what he had gleaned from his lucubrations, the prodigy reached into himself and produced elaborate designs that he aspired one day to body forth in material creations.

The young man waxed proud and vain. And when an old schoolman suggested that Melchior’s communis sensus (which is to say the compositive faculty of the mind) had in all likelihood derived a portion of its greatness from the ideas and notions that his father, the humble stonemason of Mariahilf, had instilled in him as a lad, the unctuous student bristled at the insinuation.

“All great things derive from God alone,” he had replied, fondling the Wallonian lace around the cuffs of his black coat.

Father Holzer wrote many letters on behalf of the stonemason, in which the poor man enquired after his son’s welfare. But Melchior read these without interest as he voided his bowels in the latrine, before using the paper to wipe his ass. The letters went unanswered; and when they stopped arriving altogether, the newly ordained Jesuit to whom they had been addressed never so much as asked why.

The blood boiling in Mechior’s heart bubbled up into the whites of his eyes until his glare became so dreadful that, had he been granted an audience with the Pope, His Holiness would doubtless have shifted on the Throne of Saint Peter, fearing he had committed an unpardonable offense before God and was to suffer its consequences.

It surprised no one when an emissary from the Hofburg appeared in Ingolstadt to announce that Melchior had been requested by name to serve in Vienna in the capacity of imperial architect for Her Majesty Maria Theresa von Habsburg.

On a gray Sunday afternoon in the spring of 1762, Frater Melchior von Mariahilf am Inn stood in the lower section of the South Tower of Saint Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna. He was inspecting the rooftops of the great metropolis that he had spent nearly half of his life helping to aggrandize.

Although he was in the lower section of the 446 foot tower, which the Viennese affectionately called Steffl (Little Stephen), he could see the parks and promenades beyond the battlements of the medieval wall to the south. And there to the north—at the far end of Rotenturmstraße—the waters of the Danube canal rubbed up against the city’s rotting docks.

At the base of Little Stephen was the Chapel of Notaries, whose altarpiece Melchior had been asked to touch up. Around the chapel were the graves of prominent courtiers, whose bones were disinterred after eight or ten years and moved into the catacombs beneath the cathedral. There had been talk of prohibiting the burial of the dead within the city walls, some physicians alleging that the practice was unsanitary and contributed to the spread of disease.

Behind Melchior hung the massive Pummerin (the Big Boomer), a 20 ton bell that had been cast from nearly two hundred cannonballs seized from the Turks after the siege of the city in 1683. The bell was so massive that it took nearly twenty men a quarter of an hour to work the cables before the first note sounded. The bell ringers were so adept at their job that the Pummerin rocked back and forth (in silence) at a steady tempo until a deacon signaled that the moment had been reached when the clapper should make contact. Due to the tremendous reverberations that shook Little Stephen each time it tolled, the bell was used sparingly. But at noon each Sunday the Pummerin summoned the faithful to Mass.

Because there were no pews in Saint Stephen’s, the halt and lame rested on flagstones with their backs against the nave’s broad columns. Aside from the choristers ranged in their stalls, the only other person allowed to sit during Mass was Vienna’s Prince-Archbishop, Christoph Bartholomäus Anton Migazzi, who occupied the apostolic throne beneath the limestone baldachin with his vermillion robes draped luxuriously over the armrests.

Standing inconspicuously near the baptismal font, Melchior had waited until the bell’s echoing thrum had ceased before threading his way through the crowd to the South Tower. It was not unusual for the court clergy in Vienna to treat religious proceedings with casual negligence.

Melchior had passed behind a platoon of uniformed Hussars, as the officiating priest, whom he did not recognize, led the congregation in the Collect. Once in the South Tower, he mounted the steps; and, on a landing, found a group of five bell ringers (Dalmatians all), who were sweating and gossiping among themselves as they shared a flask of wine. Melchior’s office held no mystique for them, but they recognized him as a superior and shuffled out of the way so he could pass.

Even from this elevation, Melchior could hear the Archbishop’s droning voice reciting his interminable homily. Melchior leaned out the vaulted window, so that he could better admire the gables and steeples, the turrets on the mansard roofs—and those plaster Atlantids flanking the double door of the Bohemian Chancery in the Jewish Quarter. Many of these architectural wonders he had either himself designed, or had overseen their construction; and, even beneath the pewter sky, they seemed to exude a luminous intensity.

Of all things, he found himself pondering the myth of Narcissus, who had become so enamored of his own reflection, that when he reached toward the pool to touch it, he had fallen into the water and drowned. What made me think of that myth? Do I see myself reflected in this city? Of course not. I am but an instrument of God. These creations are not mine but His.

He thought of those Tyrolean märchen concerning the dangers of seeing ones own reflection. There was the story of the Countess of Kufstein, who told her servants of a recurring dream in which a magic mirror hung at the foot of her bed. She would sit up in the dream and see her own face cackling back at her in the glass. One morning, she woke screaming. And when her servants burst into the room, they found her stark-raving mad with a cracked mirror on the wall at the foot of her bed.

Papa had warned Melchior never to look at the reflection of his own eyes on the surface of the river Inn, or the wassernixe (water sprite) who lived under the bridge would steal his soul. None of Mariahilf’s huts or buildings had window panes; and when a man in the Tyrol used a polished metal pot or glass bottle to shave by, he took care to keep his gaze fixed solely on his chin, cheeks, and whiskers.

Melchior smiled as he thought about those old wives’ tales. But when he turned to leave, he froze where he stood. Although he had rarely glimpsed his own reflection in his tender years, the boy peeping at him from behind the pilaster bore a striking resemblance to the way he remembered himself looking in the summer of 1738, when he had fallen in love with her.

“Who are you?”

The boy made no reply but tilted its head, almost quizzically.

Was it a fairy? A spiritual being? The shadow on the floor and perspiration on the boy’s brow seemed to belie this.

“Are you one of the bell ringers, my son?” Melchior asked. He rarely addressed commoners so respectfully. But in this case words “my son” fell unbidden from his lips. “Are you a foreigner? An idiot?—Speak!”

“He can neither hear, nor speak,” a woman said. “But he is, as you say, your son.” She threw back the gray hood on the cloak she wore.

“Élise?” Melchior touched his beard.

“Then you do remember my name?”

“How can this be?” She was speaking to him in German—without an accent!

Élise approached him. “There is another way out of the mountain, Melchior. A long, dark and terrifying way. My mother and I descended into this netherworld. But you sent me on that journey months before. The wound in my neck that you gave me bled unceasingly. But I could not die. In those nighted caves my mother became so frail that she could no longer go on. Before she died she commanded me to devour her flesh, so that the child inside me might live.”

“This is impossible!” Melchior gasped.

Élise lips spread into an amused rictus until Melchior saw the maggots crawling about her fetid gums. She drew aside her cloak and touched where the wound had been.

“I ate my mother’s flesh—like a beast! And when only her bones remained, I gnawed these. And the wound was healed.” A tear rolled down her cheek. “I emerged into the light. But the sun had never seemed so hateful to my eyes. Your seed had been in my womb for only a few months. But I collapsed on the bank of the river Inn and whelped four wolf cubs. But he is the only one that was not born still.”

Both Élise and Melchior looked at the boy, who crumpled to the ground, ashamed to be alive.

“When he opened his eyes,” Élise said—(and her own eyes were of a milky-white complexion)—“his attention was drawn to the bauble at my neck.” She lifted a chain from around her throat; and Melchior gazed in horror at the electrum medallion. “I knew its history—in an instant. I saw you discover it in the chapel’s altar. Now I could speak and understand German with utter fluency. For the tongues of men are as one to the Devil. . .

“I carried the newborn to Mariahilf am Inn, where I found the stonemason’s hut. I told him I had given the medallion to you as a gift; but that you had returned it to me when you abandoned me on learning that I carried your child. Your father saw in the features of the babe traces of his grandson; and was moved to bring us into his hut. He fed and sheltered us, may God have mercy on his soul.”

“Then he is dead?”

“As dead as his son became the night he placed the medallion on his neck. In doing so, Melchior, you compacted yourself to the Evil One! You were born with a great gift by which you might have glorified the Lord. I was to be your consort in the temporal world—and the Hereafter. Our life together would have been brief, but we would have brought forth righteous fruit.”

Élise cast a doubtful look at her child, clenching her black teeth. “Melchior, just as I gained the ability to speak your language, the supernumerary and seemingly miraculous acquisitions that you have so effortlessly ‘picked up’ since your discovery of the medallion are the gifts of Satan!”

Melchior snarled. “I should have killed you when I slew your brother!”

In a flash, he grabbed Élise, spun around and thrust her through the arched window. She did not resist. Her cloak ripped down the middle, exposing her hairy chest, beneath which hung the six swollen teats of a nursing she-wolf. Between her legs was a massive phallus thrashing back and forth like a serpent’s tail.

Élise bared her lengthened canines. “Melchior, you and I are the only ones on the earth who can see each other as we truly are! Join me, my love, that by our united death, the curse may be lifted, so that our son might live on.”

Melchior shoved the monster out of the window with all his might. She fell quietly with her hands pressed together in prayer, as her brother had done. Her body struck the dirt at the edge of the cemetery and a dust cloud rose up around her.

Two guardsmen had witnessed everything from a nearby alley. They shouldered their rifles and ran to where she had fallen.

From behind Melchior came a strangled cry, which sounded like the despairing howl of a wolf. When he turned, he saw the boy fleeing down the steps, loping on all fours. There was no one to obstruct the boy’s descent. Melchior ran after him and heard what sounded like claws scrabbling on the steps. But the boy was too swift to be overtaken.

The bell ringers had abandoned their place on the lower landing. And when he reached the base of the steps, he heard the Archbishop utter the words, “Ita, Missa est.” (Go forth. The Mass has ended.)

The outer door of the tower was bolted shut, so Melchior forced his way through the tide of parishioners exiting via two doors on either side of the Riesentor (the Giant’s Gate), which was closed because the tympanum depicting Christ Pantocrator was being renovated.

When he was outside, Melchior darted around the west facade, and saw three men gathered around the body. The boy was kneeling at his mother’s side. Thank God, the mute is not a figment of my imagination!

A rabbinical scholar in a caftan was comforting him. But no one dared touch the corpse, because the dead woman’s robe was torn away.

He called out to them as he ran toward them. “Seize that boy! He pushed her from the tower!” No sooner had he said this than he regretted it.

Élise now appeared as she had on the day that Melchior fell in love with her. The medallion was gone. The boy himself seemed bewildered by his mother’s transfiguration in death.

The guardsmen, who had seen Melchior commit the murder, whispered to each other in Hungarian. The scholar spoke to them in the same language. They know one another! Melchior thought. Although he could not speak Hungarian, he intuited what they were saying. The scholar was telling the guardsmen to ignore Melchior’s orders; but warning them to tread carefully since the Jesuit was an important official.

Melchior broke in on their conversation, speaking frantically in German. He dared them to challenge his interpretation of what had happened. The men smelled his fear and pretended they could not make out what he was saying.

A woman caught sight of the body and screamed. And now a crowd began to form. The boy jumped up and pointed at Melchior before plunging through the crowd and escaping into the alley that led to the Chapter House of the Knights of the Teutonic Order. In Melchior’s eyes, the boy’s gait once against resembled that of a wolf’s. But no one else saw this.

Melchior backed away until the mob had closed in around him. He sped away through the lanes Vienna, repeating under his breath, “A man who is burdened with the guilt of blood shall be a fugitive unto death.” When he had reached his apartments in the vicinity of the University Church, he glanced over his shoulder to make sure the thing he was certain was following him was no longer there.

The vapors of sleep came but sublimated themselves into a dun-colored fume. He dreamed he had found the medallion in the chapel; but he left it untouched; and thereby saved himself and Élise. But he woke before dawn, depressed when the horror of the previous day’s events returned to his mind. He decided that he would shake off his anxiety by losing himself in a familiar routine.

He wended his way through the city’s unlit streets, passing the brothels clinging like limpets to the great Bastion, still pocked-marked with ball shot from the previous century. He squeezed past a wagon illegally abandoned when the axle cracked and snuck out under the soutwest arch in the medieval wall.

Outside, he breathed the fresh air and scanned the trees and shrubs that lay spread beneath the diffused light of the moon. He gripped his dagger, because he was now beyond the city limits; and the footpads lay in wait. A dirt path meandered through the woods to a cobbled lane. He saw the building he was heading to: the church of the Congregation of Saint Michael the Archangel—also known as the church of Mariahilf.

The Tyrolean artist Paul Troger had begged Frater Melchior to replicate his famous trompe-l'œil of Our Mother of Mercy; but, this time, in a side chapel of this newer church that had been erected in the wake of the Turkish siege to serve as a spiritual bulwark should the Sultan’s forces ever return.

When Melchior was inside he made doffed his cloak in the vestry and donned a painter’s smock. His brushes and paints were stored in the wooden chest on the other side of a tarp draped between the pillars. The sun had not yet risen, but the interior of the church was ablaze with candles.

The only sounds in the church were the cooing of the pigeons roosting in the rafters and the footsteps of the acolyte tending to the candles. The boy was near the side chapel and regarded the Jesuit with a look of unease, but bowed at him before hastily walking away.

Melchior lifted a candle from a sconce and (stepping under the tarp) used the flame to light one of the lanterns on the scaffold. He bent down to unlatch the chest, and glanced quickly at the mural.

Then he set the lantern down and stood up, covering his mouth with his hand.

Someone had defaced the painting. The saints beneath the mitred Virgin’s cloak had been transformed into wolves. The Holy Mother was naked—her body a travesty just as Élise’s had been before Melchior pushed her to her death.

He spent the morning obliterating the image; and then scraped the wall underlying plaster showed through. Then he informed Herr Troger that a better artist than he would have to be found to complete the mural in the side chapel because his inspiration had fled him. He was certain the acolyte had seen the abomination. But surely the boy will be too terrified to speak of the matter.

Later that day, Melchior approached his superior and explained that he needed to spend a month at the Order’s retreat on the Kahlenberg. Permission was granted and by the next afternoon, Frater Melchior was comfortably situated into his private cell; and had met the four servants who would be attending to his needs during his stay.

Shortly before Vespers, he lit a candle. His heart was racing. Something was happening to him. His eyes burned when he looked at the crucifix on the wall. He clasped his hands together and prayed for forgiveness. He remembered a sermon Father Holzer had delivered long ago in Mariahilf am Inn.

“Many wait until the end is nigh to ask for God’s forgiveness. But that is to pray out of fear. It is an empty gesture. If we are to ask for the Lord’s forgiveness, we should do so out of a genuine sense of remorse.”

Melchior toyed with the Wallonian lace at his cuffs; and thought of how proud his father had been on the day he had departed Mariahilf for the University of Ingolstadt. The stonemason’s son now felt ashamed that he had never responded to his father’s letters. “I’m so sorry, Papa.”

“It’s too late,” his father replied.

Melchior gasped and looked behind him as the candle blew out. Suddenly, he heard what sounded like a wolf running across a wooden bridge. By the fading twilight filtering into the cell, he discerned what had caused the noise. A nail had snapped at the top of the crucifix, which now dangled upside-down by the spare nail driven through the Savior’s feet.

Brilliantly done again, Daniel. Melchior might be a monster but he seems to have unleashed something even worse on the world

Interestingly on Narcissus, we actually have a print of the Caravaggio painting in our living room. Always been one of our favourites. Don’t know what that says about us! 🤔😁

Well Daniel, the story is starting really to take shape by the threads being woven together like a tapestry. Poor Melchior caught in his own self righteous trap is facing his doom it seems. But his son is now loose upon the world! A terrible prospect that we have already been witness to I think.