The Werewolf of Mariahilf am Inn I.12

A Gothic Horror Novel

Book 1, Chapter 12: The Figures in the Window

List of Chapters | Previous Chapter

It coursed through his veins and spoke to him when he slept. A demon of smoke and muffled sighs. It wasn’t the werewolf. Not entirely. But the werewolf was somehow woven into it. It was the morphine that Hermann had resorted to in the months following the tragedy. I don’t smoke it, he thought. I inject it. Yet my brain coughs and gags as though suffocating. And the months fall away as the withered leaves of autumn.

What were these long-forgotten childhood memories that rose before him with a significance they had not had before? The fog thinned but never faded as he wandered a phantasmagoric Tyrolean village that bore only a passing resemblance to the Mariahilf am Inn of his youth.

Clad in his little-boy britches, and a matching coat made by Aunt Magda, he would find himself pursued by that dark-haired lady wreathed in an aureole of light that should have inspired awe but only magnified his dread.

Oma Ingrid told him it was the Blessed Virgin watching over him. But Papa claimed it was his dearly departed mother, Ilse, who (even in death) could not bear to be away from her only child. With both adults affirming the presence to be benevolent, Hermann no longer feared her, even when she crept behind him in the shape of a giant wolf.

How could I have forgotten this? No, I didn’t forget this. It never happened. This is all a dream.

And he would try to wake but couldn’t, because the numbing drug unnerved him and sapped him of his will.

And the dead cannibal laughed as he turned a wooden crank in the carnival tent and the backdrop of the shadow-play advanced to the next scene. Hermann peered through the peephole, Papa’s hand on his shoulder. And he saw again that gray morning when Oma handed him the bowl of charred tripes, atop which lay a grilled chicken gizzard. She told him to feed the madman imprisoned in Papa’s workshop. “But don’t talk to him or he might enchant you.”

The same trepidation Hermann had felt that morning came back to him now, as the roaches crept from the bowl and scuttled over his hands and wrists. And he somehow knew that if he dropped the bowl, he’d die. The swift-moving legs tickled his forearms, as the workshop door opened and a clawed hand emerged, beckoning him to enter. “Shhh. It’s the boy,” a voice whispered.

Then a chicken clucked because the gizzard wiggled. And this made the carnival-goers laugh, because Oma Ingrid was mimicking the cluck as well.

—Hermann jolted awake and sat up, as a voice on the other side of the room said, “Shhh. It’s the boy.”

It was morning. The bed he’d slept on was too narrow to share with Henrietta. He wore the clothes he’d had on yesterday afternoon when he’d injected himself. There were no insects on his skin, although the drug sometimes made him feel as if there were. He touched his ear because he heard a chicken cluck again.

He turned and looked at Henrietta, who was tied to the chair in the corner of the room. Her head rested against the bolster between the top of the chair and the wall. It was she who had made the noise, because—to his horror—roaches were scurrying up and down her body.

Some of them had entered her mouth and she had swallowed them, but since she was dehydrated and her tongue was swollen, she was now retching and making clucking noises, because she was choking.

“Oh God!” Hermann exclaimed.

He leapt from the bed and rushed to her side. He scooped the insect pulp from her mouth. She could not bite down because her jaws were locked open. He undid the rope around her waist and lowered her to the floor. He bent back her neck and breathed into her mouth. She exhaled and vomited up droplets of chyle, before emitting an unconscious groan.

Hermann fetched a sponge and basin of water. He sat beside her on the floor, squeezing water from the sponge into her mouth. He rose again and fetched the same pitcher and a wooden cup. For an hour he sat nursing her, replenishing her fluids. And when her muscles had relaxed, he carried her to the bed and laid her out on it.

He collapsed in the table chair and stared at the syringe. The bruises in the crook of his arms itched. How is it already October?

The doctor had kept him sedated for three weeks after the murder of his children and in-laws. Once he’d been roused, Hermann had had no time to dwell on the novel aches and pains that now plagued him.

But two days after they moved into the apartment above the bakery, Hermann decided to consult the pharmacist in the apotheke on the other side of the square.

Thanks to the generosity of his American friend, Marty Fitzsimmons, he would not have to pay rent until the following spring. And the king’s ransom Marty gave him “as a gift from a friend” meant that he and Henrietta would not starve through the winter. But before heading out to scout for a job, Hermann needed to get to the bottom of what was ailing him.

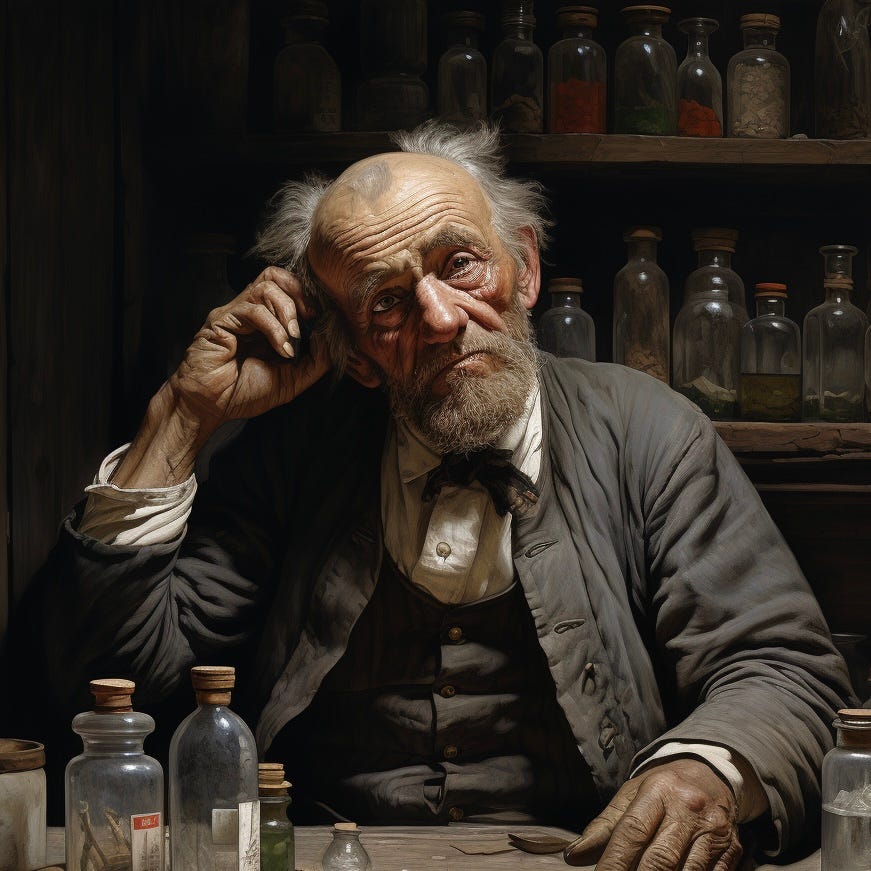

The raddled pharmacist stank of peppermint schnapps and resignation, but his grizzled features were keen and he had a kindly disposition.

Hermann explained his situation as best he could. “I scratch my arms and legs continually because of an itch that won’t go away. I can’t sleep. I wake at odd hours of the night, panicking.” In general terms, he alluded to certain “traumatic events” that might have contributed to his physical deterioration. He mentioned offhandedly that he had been kept under sedation for three weeks.

“I recognize you, Herr Tischler,” the pharmacist said. “The doctor who treated you procured the medicine from me. First, my condolences. What happened to you and your family, is absolutely incomprehensible. The fiend who committed these atrocities is surely a creature of Hell.”

Hermann’s eyelids fluttered.

The pharmacist scratched his ear. “I believe your physician meant well, but opiates are known to cause secondary effects similar to the ones you describe.”

“Is there a cure?”

“The symptoms have been known to go away on their own. But it can take time.”

“How much time?”

“No one knows for certain. But research suggests that using the same drug in moderate and restricted quantities could expedite the process. I have morphine here, as well as a syringe that I could sell you. And by the grace of God, you will be able to wean yourself off of it by Christmas. But you mustn’t overdo it, or you will become habituated.”

“What does that mean?”

“It means that you might acquire a dependency on it.”

Hermann didn’t want to look foolish, but the pharmacist was not really being clear as to how much he was supposed to take to get rid of these symptoms.

The old man coughed and wrote out a general regimen on a slip of paper. “I would skip every other day, since it’s already been over a month since you were last subjected to it.” He weighed a quantity of the drug on his brass scales, tore pages from an outdated almanac, and used these as wrapping paper. He gave Hermann a small brochure with pen-and-ink illustrations that explained how to prepare the morphine for injection.

Hermann balked at the price.

The pharmacist shrugged. “It comes from the Punjab, you know. Turkish middlemen and whatnot. Then it’s refined here, in Hesse-Kassel, by the Family Merck of Darmstadt.”

Hermann nodded as if he understood what the man was talking about.

“As for the syringe, it’s manufactured in Scotland. So the hypodermic needle, which is hollow, is quite dear. I would recommend boiling it regularly to prevent it from rusting. Should you need to come back for more, your subsequent purchases will not nearly be so costly.”

He handed Hermann the syringe case. “I don’t know why the English package needful instruments in velvet-lined morocco cases. An unnecessary extravagance.”

That night, Hermann prepared a small dose and injected it into his arm. He slept soundly and woke the next morning in a state of euphoria. He felt settled. He went about his morning chores with a vigor he had not known for months. He fed and bathed Henrietta, massaged and manipulated her limbs, laid her out on the bed, fluffed the pillow, and kissed her forehead.

He washed in the common lavatory at the end of the hall, which he shared with the landlord’s servants. Then he dressed and headed out to find work.

His first stop was the wheelwright factory owned by Adolf Goltz. Adolf had been Berthold Landecker’s rival. But the two men had grown close in the final years of Berthold’s life.

Now in his seventies, the elderly industrialist ushered Hermann into the office overlooking the showroom, and set a paper on the desk between them. He shook his head mournfully. “Colonel Landecker’s solicitor sent this to me last week. As I understand it, I am not the only manufacturer in the Upper Rhine to have received a copy.”

Hermann picked up the letter and read through it:

Hermann Tischler worked for my uncle for over 15 years. He claims to be a carpenter, but has never been accredited by a guild-master. Though my uncle’s business is now dissolved, Hermann Tischler was trained in the Landecker Werke’s methods and practices, which are proprietary and may not be shared with any industrialist, tradesman, or corporate body operating under the aegis of the German Zollverein (Customs Union). Hiring Hermann Tischler as a carpenter, woodworker, wheelwright, or in any capacity ejusdem generis, will result in the Landecker estate raising an inquiry into the matter.

The revelation fell on Hermann like a hammerfall. He thought of every interaction, every conversation, he had had with Ludwig over the years.

What offense did I commit against him? What has led this man, whom I once considered a brother, to hate me so much?

He realized that if he fixated on this wrong, his bewilderment might turn to rage—and in the cauldrons of rage, murder seethed beneath the bubbles. Vengeance is mine, says the Lord. If thine enemy hunger, feed him; if he thirst, give him drink: for in so doing thou shalt heap coals of fire on his head.

Hermann returned to the lodging that day, exhausted and in tears. That night, he whispered into Henrietta’s ear, “I live only for your sake now.” Then he turned to the tranquilizing powers of the morphine.

And the days turned into weeks as the weeks ate up the days; and the more he took the drug, the more he found himself waking only to sleep again. I fed and watered my poor dead wife this morning. She’ll be fine. Just one more dose.

Between frequent bouts of listlessness and insensibility, fleeting moments of lucidity would intervene, during which he would recognize that time was not on his side and that he must find a job or else the two of them would run out of money.

“Then what will become of you, my love?” he would say, sometimes to Henrietta, and sometimes to the syringe.

The citizens of Cronenberg had seemingly closed ranks against him. For they are a stiff-necked people. They discussed Hermann Tischler’s story, and circulated rumors implying that he had not been entirely guiltless in the dreadful affair of Holy Saturday, 1867.

Men and women he had known and been friends with in former times now averted their eyes when they met this frail wraith on the street. Hermann would grit his teeth and fitfully scratch his scalp, muttering to himself as he negotiated the crooked lanes of crooked Cronenberg.

He stopped attending mass at St. Laurentius in Elberfeld, because the very thought of standing shamefacedly in the house of God, without his family or wife was insufferable. He prayed when awake, because he thought this would keep the demon at bay as he slept. But the longer I sleep, the less time there is to pray when awake.

On the last Thursday of October, while passing through the marketplace, he overheard a woman call out to him. He looked up and saw Frau Jeismann, the landlord’s wife, standing at a grocery stall, signaling to him.

She was about to hire the grocer’s son to carry two baskets of produce to the townhouse. Hermann grinned and ran to her, hoping she would find it in her heart to pay him for this task, a “task” most would consider an obligation due a lodger to his landlady.

“Herr Tischler, would you be so kind as to carry these baskets and walk with me? There is a matter I would like to discuss with you.”

“Of course,” he replied, standing up straighter than he had in weeks.

A gust of wind blasted through the marketplace. Frau Jeismann touched her hat.

“Goodness! The season is certainly upon us. . . What I wanted to say is that the Sisters Rother, who operate the bakery beneath your room, have confided to my husband that your poor wife is standing at the window at odd hours of the day.”

“I’m afraid that’s quite impossible. My wife—”

“Yes, Ephraim told them of your wife’s condition. But they insist it is she who is standing there. They have complained that she is frightening away prospective customers. I thought it was nonsense myself. . . ”

There was something she wanted to add; but she seemed unsure how to proceed.

“Yes?” Hermann asked.

They stepped onto the sidewalk to avoid an oncoming dray cart.

“Each week our daughter and her family break bread with us on the first meal of Shabbat. Last Friday, as they crossed the square, they saw your wife standing at the window. Beside her was a man costumed as a fairy-tale wolf. He made lewd and shocking gestures that were inappropriate for the eyes of children.”

Hermann’s throat went dry.

“We are in Cronenberg’s Old Town,” Frau Jeismann continued. “Residents of this quarter are expected to comport themselves in an unimpeachable manner consistent with the statutes published by the town fathers. I make no threat, Herr Tischler. I am simply providing you with information, should you wish to maintain your tenancy in the building.”

The bakery was open and busy by the time they reached the square. Both Hermann and Frau Jeismann glanced up at the window, but there was no one there. They entered the door beside the shop and ascended the staircase.

On the first landing was the corridor leading to Hermann’s room.

“You may leave the baskets here. I shall have our man retrieve them.”

“Yes, Frau Jeismann.” He set them on the floorboards and mopped the sweat from his face. His cheekbones felt sharp.

“Herr Tischler, will you please accept a lemon from that basket there as a gift? It is from Italy.”

Hermann exhaled, disappointed. He needed money, not food. He removed it and thanked her.

“I would recommend expressing the juice into the water you and your wife are drinking. Your gums are black.”

Hermann nodded, sullenly. But his eyes lit up when she reached into her reticule and removed three coins. She placed these into the palm of his hand.

Three Vereinsthalers! Four months’ worth of rent! What an act of unexpected generosity!

“Herr Tischler, you should consult a doctor. If you are suffering from a mortal illness, it would behoove you to settle your affairs before you succumb to it. Your wife has suffered so much already. You must ensure that she will be taken care of in the event that you predecease her.”

He smiled politely, thinking only of the coins in his fist. She turned and continued up the steps.

Hermann walked down the corridor until he reached the door of the room and turned the handle. The door had no lock. When he entered, Henrietta was in the chair he’d left her in. Her eyes were closed. She was asleep.

There were no curtains in the room, because the apartment had not been furnished with them; and he had no interest in wasting money on such fripperies. He stripped the sheets from the mattress.

He was glad he had not yet sold the hammer and nails that had been among the items he had been permitted to take from the mansion on the day they were evicted.

He nailed both sheets to the top of the window frame, then secured them with two more nails under the sill so they wouldn’t flap about when the wind blew through the cracks in the walls. The heat from the bakery below kept the room surprisingly warm. And he had two woolen blankets that he and Henrietta could use during the winter.

His head pounded. He wanted a dose, but it was not even noon.

He decided to do as Frau Jeismann had advised. He cut the lemon in half, poured water into a cup and squeezed the juice into it. Then he helped Henrietta drink the water, noticing only then that her gums, too, were black. Once done, he made sure the rope around her waist was loose enough for her to breathe comfortably.

Still too early.

He removed the coins from his pocket. Three Vereinsthaler would mean he could sleep the special sleep through the weekend, since no one needed workers on Saturdays or Sundays. He would go look for a position on Monday when his head no longer hurt.

How many times have I said that?

He sat down at the table and arranged the coins in a row. He wondered if there were other chores Frau Jeismann needed a handsome young buck to help her out with. He wiped the grin from his face, then planted both elbows on the table and sobbed, because evil was prevailing. What was it Henrietta said in the alley behind the church on Palm Sunday? “The Devil triumphs when a good man is brought to despair.”

In the center of the table stood the memento mori, the wooden figurine his father had carved out of a single block of wood during the winter of 1845. How could I have been so foolish? I can sell this thing. He’d already pawned the morocco case the syringe had come in. The broker will surely give me a good price for this as well.

Moments later, as he depressed the plunger and felt the poison flood through his veins, he recalled what Papa said when he asked why there were worms in the belly of the wooden man, who held a lantern in one hand and was peeling back a flap of flesh with the other.

“The worms are there to remind us that, even though we walk the Earth by the grace of God, we are already dead.”

Daniel I was so glad to see another chapter but very sad that Hermann and Henrietta have reached new depths of suffering and despair. Certainly opiate addiction was not an uncommon addiction at the time. I noticed that you chose morphine as the drug that Hermann was offered by the pharmacist. It was available in that timeframe and the syringe was recently invented. Just wondering if you considered using laudanum which was even more common and more easily administered? Obviously not a critical detail but something that crossed my mind. Clearly the horrible dreams and hallucinations could be entirely attributed to the opioid consumption, but one wonders considering the reports of sightings of Henrietta and the wolf figure at the window. Or could this be an invention by the landlady as an excuse to remove them because of pressure from the local community? Anyway, eagerly awaiting the next installment with some hope for a ray of sunshine even though briefly!

The saga continues!!! What a book this is going to make. 😀