Book II, Chapter 11: Sapere Aude

List of Chapters | Previous Chapter

Benedikt took a second drag from the cigarette he had rolled upstairs. Then he handed it to Hermann. The two men stood with their backs to the carriage house of the Eltzbacher Coach Inn. It was only 5:00 p.m. but the sun had already set. There were no clouds in the sky. The stars were twinkling and the moon cast a glamour on the snow.

Earlier that day, Benedikt had told Hermann the story of his unholy birth. The Austrian man was still reeling from the ramifications of it all. I was born still. And yet I live.

One of the carriage house’s folding doors—the one in front of the landau—stood open with its vertical stile-rod sunk in the ground to keep it from blowing in the wind. Inside, they heard the door at the top of the staircase bang shut, followed by the distinctive tread of Walter coming down the steps.

The boy joined them outside. He leaned his back against Hermann’s chest and thanked him for letting him keep the one-eyed cat, which he had named Mürrisch (Grumpy). Instead of responding, Hermann passed the cigarette to the orphan, who took a long puff and contemplated its smoldering tip like a connoisseur.

“That’s real tobacco,” he said. “It’s very good.”

Since the bunk rooms had no doors, the cat was currently pent up in the room Walter slept in by means of a heavy piece of wood reinforced with iron that Hermann had brought inside from the stable. The tall board leaned against the door frame in such a way that it made a small wedge-shaped opening near the floor through which the cat’s paw probingly emerged, often accompanied by a plaintive yowl.

“You know,” Benedikt remarked. “Just because we’re letting you keep the cat, doesn’t mean we’re happy about it.”

“I know,” Walter replied. “Monika said you were both pissed off. She told me I have to wash him in the tub tomorrow. She’s going to boil water for me to do that.”

“It’ll scratch you to ribbons when it gets wet,” Hermann remarked.

“It’s not an it, it’s a he,” Walter said. “He’s a calm cat. I don’t think he’ll scratch me. If he does, I don’t really mind.—Better than working with those damned horses. One of them bit me today.”

“I thought you wanted to work with the horses,” Benedikt said.

The boy greedily finished off the cigarette before replying. “I thought I did too, but I don’t.”

Hermann sniffed. “So you’ll waste time looking after an animal you’re not getting paid to look after.”

Walter cast the butt into the snow. “I worked harder than both of you today. I had to get up early and clean the stables. Then I fetched water and helped Monika cook breakfast for the guests, because the girls from the village didn’t show up until about an hour after the sun came up.”

“That’s funny,” Benedikt said. “Monika told me that you spent half the day lounging around in the common room listening to Herr Eltzbacher tell stories.”

The boy exhaled. “I’m tired of you guys ganging up on me. You don’t have to worry about the cat. I’ll take care of him and clean up after him. But I’m exhausted now. And I’m going to bed.” He gave Hermann a quick hug and returned to the carriage house, stomping up the steps so as to telegraph his irritability.

When he was gone, Benedikt and Hermann grinned at each other.

“I’m feeling refreshed,” the ostler said. “I could tell you more of the story. But I would rather not do it here. Voices carry in the dark. How would you feel about going into the village? We could have a hearty meal at Herr Mattner’s pub.”

“It’s Sunday.”

“We’re in the country. The villagers here are not so strict about such things.”

“I haven’t the money to waste on—”

“I’ll pay.”

Hermann smiled. “I would be obliged.”

Benedikt turned around and cupped his hands over his mouth. “Monika!”

A window on the upper level opened, cracking the ice on the sill and dislodging a clump of snow that fell on the barrel below.

“Yes?”

“My love, there’s no need to prepare a meal for us. Brother Moritz and I are going into town to eat.”

“Oh?” Monika said. “That’s a relief. I’m feeling a bit fatigued and had hoped to turn in early.”

“Do so. We’ll be back shortly. I’ll make every effort not to wake you.”

Within minutes they were in the village; and, since it was a Sunday, the main thoroughfare was not as crowded as it had been on the night of the meeting. But it was also December 18, 1870, the first night of Hanukkah, and many of the windows were aglow with the twin lights of the central shamash and the candle in the rightmost stem of the festal menorah.

The public house stood on the near side of a timber bridge spanning the frozen-over millrace, and beyond it were the icy steps along the edge of the barge canal. Benedikt pointed to the bridge and said, “It’s not as large as ours was in Mariahilf. But the snow on the rails this time of year always reminds me of home.”

There were a handful of patrons in the taproom, all at the bar. Since the publican had accompanied the town’s Bürgermeister to Kohlendorf, Hermann and Benedikt were greeted by his venerable wife, Frau Mattner, who wore a scarf wound up to her chin because, even though the front room was cozily heated by a massive fireplace that looked as if it belonged on the set of Mozart’s Don Giovanni, it was still not as warm as Frau Mattner would have wished it to be.

Benedikt asked if it would be possible for each of them to procure two chops of “whatever you have available,” along with some warm cider. And he asked if they could take their meal in the private snug at the back of the establishment.

This was the most princely order that had been placed all week. Recognizing Benedikt as the employee of Frau Eltzbacher, the withered beldame led the two “Junkers” through the stone archway and into the private room. She wiped dust from the cubby table and (with a worried sigh) doubted they would be comfortable here, since it was admittedly much, much cooler than the front room. But both men insisted that it would be fine and that they would simply eat with their coats on.

Frau Mattner primed the oil lamp over the table, which squeaked as though it mourned the loss of its three months of neglect and disuse. Then, coyly touching her nose, the matron disappeared momentarily, returning with a flaming paper by which she kindled the lamp, along with two melted-down candles in tin dishes on the table “to better see the vittles by.”

Exiting through the archway with an imperious flounce of her white apron, Frau Mattner kicked open the door to the kitchen and yelled at her middle-aged son—who was curled up on the stove fast asleep—ordering him to wake up, stoke the fire and start pounding four schnitzels for their customers.

Immediately upon her departure, Benedikt launched into his narrative.

“The cannibal of Mariahilf am Inn was hanged late in the summer of 1848, the ‘Year of Revolutions’ as it became known. From far and wide, Austrian secular authorities, along with representatives from Rome and the various religious orders, converged on the valley where the trial was to take place.

“One of the first to appear was an aged friar, a Franciscan who volunteered to distract the children from the horrors of the proceedings by instructing them in the Catechism and teaching them how to read. He spoke German fluently, but with a thick Italian accent. He gave us to understand that his name was Fra Matteo di Pàdova.

“Because Father Reuss was preoccupied with a host of administrative affairs related to the trial, he did not have time to spend with me. As a favor, he implored me to assist the Franciscan on his mission. And so I sat beside Fr. Matteo in the tent, which my uncle erected on our property to serve as the village’s improvised schoolhouse. The man had an odor that was earthy and raw; but not rank or disagreeable.

“I was impressed by his unorthodox approach to education. On a slate board, he would write letters of the alphabet and arrange these into simple words and sentences, directing the children to repeat after him as he sounded them out. Each child learned to print his or her own name and write it in autograph.

“He did not teach the Catechism (as he had promised), nor did he expose the children to Latin, which led me to deduce—erroneously as it turned out—that he did not know that language. The children listened to him spellbound, because he would often divert them with folk tales and draw parallels between these and stories from the Bible.

“It is with some amusement that I recall that you did not seem interested in learning to read or write. Nor did your grandmother or father encourage you in this endeavor.”

“I learned to read a few years later,” Hermann remarked with a frown. “My wife taught me when we were still quite young.—Henrietta; that was her name.”

Benedikt touched Hermann’s wrist sympathetically before resuming his story.

“Fr. Matteo was extremely curious about the madman incarcerated in your father’s workshop. He asked me on several occasions to take over the lessons so that he could attempt to catch a glimpse of the accused. But he was denied this opportunity each time. There was so much secrecy about the trial, Hermann. You cannot even begin to imagine. There was a point when Father Reuss himself was no longer permitted to hold converse with the creature.

“I was twenty-seven at the time, and Father Reuss thought it imperative for me to decide upon a course of life. ‘What do you plan to do with all the education I have crammed into your skull?’ he asked me.

“‘All I know is that I don’t want to be a horse breeder,’ I replied, shrugging and staring at the floor like an imbecile.

“It was the last Sunday before the execution was to take place. Having concluded his sermon, Father Reuss summoned me and Fr. Matteo to his residence. The friar entered barefoot—discalced (as they say)—and turned up his nose when Father Reuss approached, because this hospitable movement had shaken the scent of lavender from the priest’s immaculate cassock.

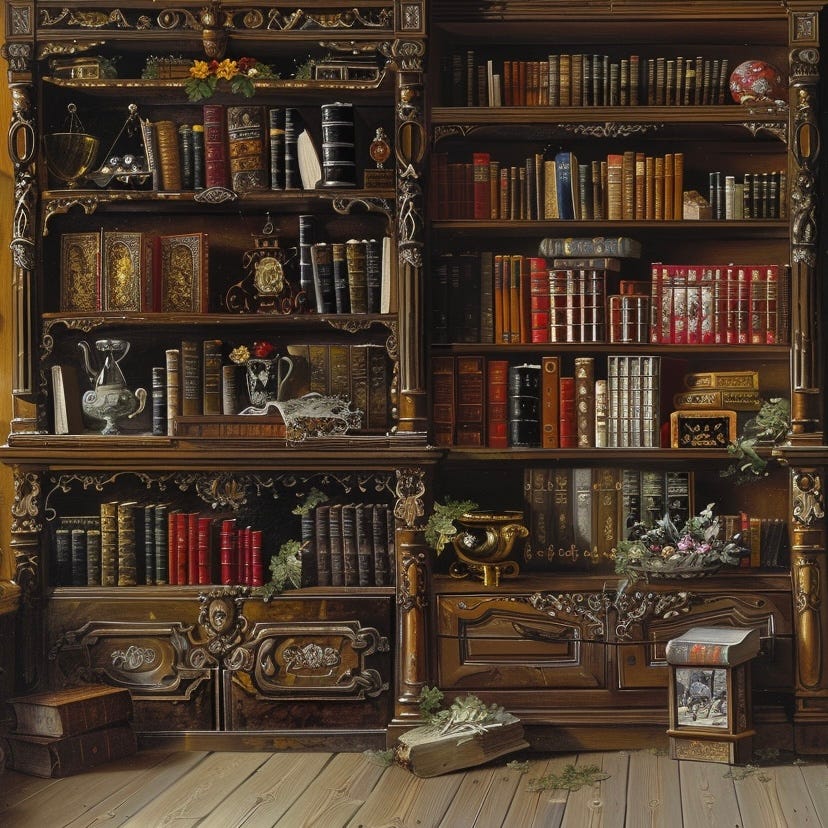

“My mentor regarded the mendicant at first with an expression of high-handed disdain, but this melted into awe as Fr. Matteo scanned the titles on the shelves of the two bookcases and began to recite exemplary passages from the works of Horace, Virgil, and Seneca.

“Father Reuss expressed astonishment that so humble a servant of Christ should have such an exacting and comprehensive knowledge of the profane literature of the ancients.

“The friar flashed him a brittle smile, touching the spine of the De Rerum Natura of Titus Lucretius. ‘Nil posse creari de nilo,’ he said, which is a Latin phrase meaning ‘nothing can be created from nothing.’ Father Reuss had never allowed me to read this work; and I saw him now flush in embarrassment.

“Fr. Matteo knew why he had been invited here. ‘You would like me to take the boy on as a postulant,’ he said. ‘A bit long in the tooth, but I if he hears the call and whatnot. . .” He made a bland gesture with his hand. ‘At the very least,’ he said, softening his tone, ‘I can make him into a passable schoolmaster. He is patient. He is kind. He is bright.’

“‘There you have it,’ Father Reuss said with a smile. ‘It is decided.’ He embraced me fondly, and drew from his shelf a volume of Cicero’s De Officiis bound in tooled leather with a silver latchet. The suddenness of the decision quite overwhelmed me with conflicting emotions. I turned to each, and asked if I could spend the rest of my time in Mariahilf at home with my family to prepare for my journey and say my final farewells. My request was granted. . .

“And now, Hermann, I come to the fateful night of the cannibal’s execution.”

—“Execution?!” Frau Mattner exclaimed, stepping into the private room. She put two steaming cups of cider on the table. “I hope you’re not telling ghost stories. They’re especially scary this time of year. We’ve got a ghost here, you know?”

“I didn’t know,” Benedikt said.

“Oh, yes! He gets up to all kinds of mischief. Blows out all the lights at once. That sort of thing.”

“How do you know it’s a he?” Hermann asked.

“Because lady ghosts aren’t so rude. Your food will be out shortly.”

When she was gone, Benedikt and Hermann sipped from their cups.

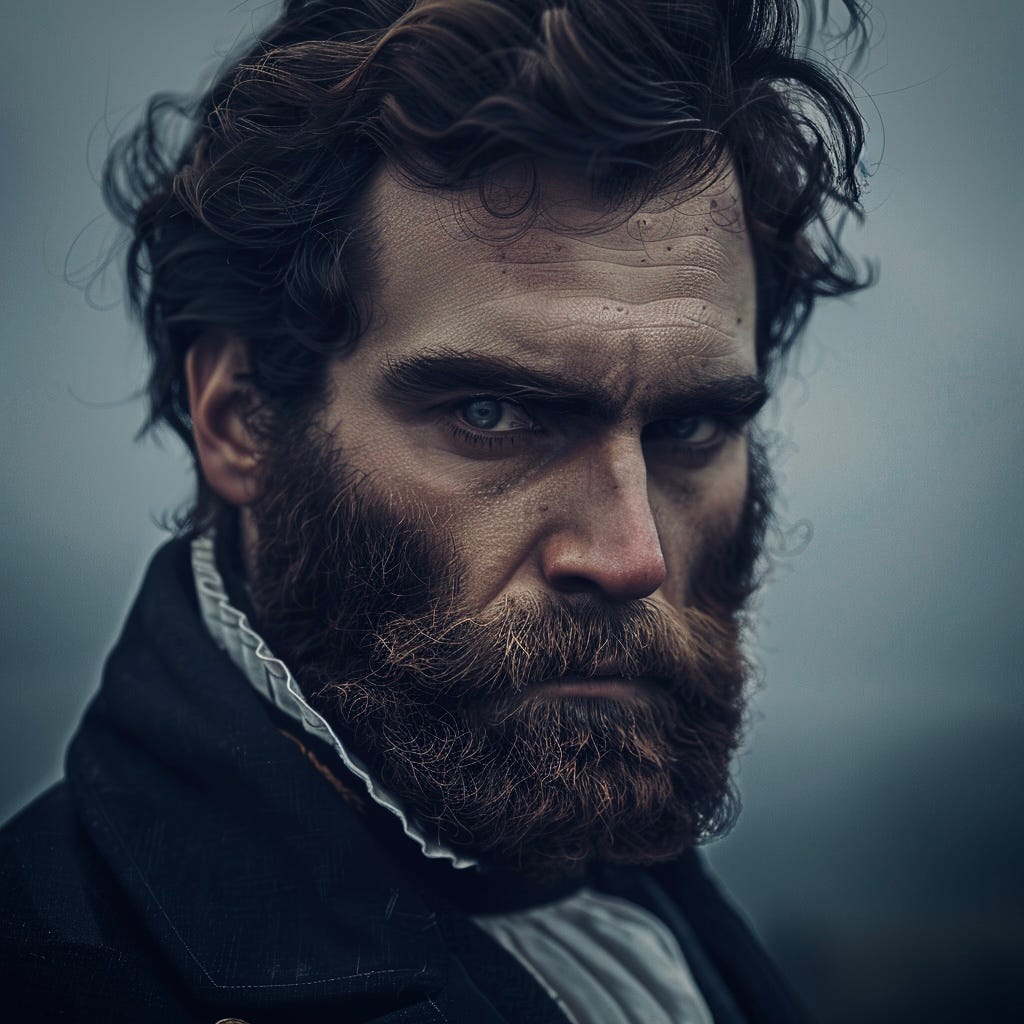

“On the night of the execution,” Benedikt resumed, “Fr. Matteo and I stood behind you and your father. When the black hood was removed from the condemned man’s head, I heard the aged mendicant gasp. At the base of the scaffold stood Father Reuss, asking the creature if he repented for his crimes, and if had any last words before he was to die.

“The monster seemed to transfix both you and Fr. Matteo with the same penetrating gaze. It spoke in your mother’s voice—even the voice of Ilse, saying, ‘Little boy, little boy. Remember what I told you. . .’”

Hermann gulped down the scalding cider, as the tears welled in his eyes.

“No sooner had these words been uttered than Fr. Matteo whispered, ‘And so it begins as it ended long ago.’ I glanced at him curiously, and at that instant the blacksmith hammered the block out from under the wretched man’s feet. The rope went taut. The man was hanged. The rest, you know.

“They cut off the cannibal’s head and dumped the body in a pit dug out of that same charred depression in the valley, where Father Reuss and I had buried the accursed electrum medallion in the wake of your birth. Once the grave was filled in, the men of the village kindled a bonfire on the mound that blazed bright until the break of day.

“My mother prepared enough food to last me and Fr. Matteo for a week. I embraced my father and mother, my uncle, cousins and siblings. And together we went to the stables so that I could say goodbye to the stallion I had raised since he was a foal. This done, I walked to the Mariahilf Church where Fr. Matteo awaited me on the steps. At the residence I could see that Father Reuss had drawn the curtains shut to signify that I was no longer his responsibility.

“We followed a Venetian delegation up the winding mountain path that linked up to the highway out of Innsbruck that led to the Brenner Pass. But as the wagons trundled on between the ridges of rock, Fr. Matteo touched my shoulder and announced that we would be traveling a different way.

“We climbed an unmarked trail that brought us to a jagged bluff. He went directly to the precipitous ledge where the murdered woman and her four babies had been found. Black gouts still discolored the karst rock where the innocents’ blood had been shed. There was a massive boulder that teetered on the brink. It seemed to me that it oscillated and that the slightest pressure would cause it to tumble into the crags below.”

Hermann leaned into the table. “I know the place whereof you speak. It is there that I first set eyes on the werewolf.”

“I did not know this,” Benedikt said. “This sheds an interesting light on what I am about to tell you. . .

“The morning was clear and peaceful. Fr. Matteo leapt onto the boulder and plopped down, facing me—but looking beyond me to the village below. This transformation was unexpected, almost comical. But his visage waxed dour and his tone became stentorian.

“‘I have brought you here,’ he said, ‘to make a confession. I do not believe in the God of the Bible; and, though I follow the way of Christ and revere him as the greatest of teachers, I do not regard him as divine or the very son of God.’

“I threw my shoulders back, incredulous. ‘That is blasphemous! You are pretending to be someone you are not!’

“‘I could say the same of you,’ he said, glancing up at the clouds. ‘I could say the same of the greater portion of mankind. Sapere aude, Benedikt!—Dare to know!’

“‘Why did you bring me to this place?’

“‘To reveal to you the truth about me before you commit to accompanying me on your journey.’ He scratched the white bristles on his head. ‘You may return to Mariahilf if you wish. I harbor no fell intentions, nor have I any dark designs against you. But if you agree to come with me, there is no turning back. And you must swear never to divulge the secrets that I shall reveal to you to any but to him for whom they are intended.’

“‘Whom do you speak of?’

“The color drained from his wizened face; and when he spoke again, the words fell from his lips as if he had read them long ago: ‘Little boy, little boy, remember what I told you. . .’”

Hermann exhaled and leaned back against the snug’s creaking boards.

Benedikt gripped the cider mug between his palms. “I was frightened by the man’s strangeness. Yet exhilarated. I looked over my shoulder and contemplated the black smoke rising from my family’s chimney pot. I knew that I stood at the most important turning point of my life.

“‘If you do not believe in God,’ I said, ‘then by whom am I to swear this oath?’

“‘I did not say that I do not believe in God,’ Fr. Matteo said wistfully. ‘I said that I do not believe in the God of the Bible.’

“I have often wondered what would have happened to me had I remained in the village. Doubtless I would have succumbed to whatever mysterious calamity befell Mariahilf am Inn soon after my departure. . .”

Benedikt doesn’t know how his family perished. It torments him still. I must find a way to tell him. But not now. Not before I learn where this skein leads.

Benedikt contemplated the guttering candles. “I told Fr. Matteo that I would join him. ‘Accept me as your disciple. And I swear to God that I shall not share the secrets you reveal to me to any but to him for whom they are intended. . .’” (The ostler’s eye bore into Hermann’s.)

“With a nimbleness that surprised me, Fr. Matteo stood up, habit blowing in the wind. ‘Come,’ he said, beckoning to me. I climbed up and stood beside him on the boulder. But I trembled and closed my eyes, for I have always had a great fear of heights.

“‘Follow me,’ he said; and before I could respond he leapt from the boulder onto a shelf some five feet away and three feet down, which projected from the mountainside.

“‘What are you doing?!’ I screamed.

“The alpine gorge beneath us was alive with rolling vapors.

“‘I told you that we would be going a different way.’

“I did not want him to think me a coward. I took a step back, made a running start, jumped and landed on the shelf. But then I collided with him and we fell together on the narrow ledge, dislodging a pile of rocks that tumbled over the cliff, and quietly shook the branches of the firs below.

“‘I’m sorry, Master,’ I said.

“‘It’s alright. We only have two leaps to go.’

“‘Two?’

“‘Yes, that was the first.’

“‘I’m feeling dizzy. I want to go back.’

“‘I told you there is no going back.’ He pointed to the round boulder we had jumped from, which was now too far away; and too high for us to spring to. ‘Before we go on,’ he remarked, ‘take note of those iron rings. There is a story behind them.’

“My eyes were still adjusting to the empurpled dimness of western slope, but I discerned the rings he spoke of. There were several driven into the stone in an oblique line leading down; but they had rusted to such a degree that their brown hue made them nearly indistinguishable from the mud impacted between the clefts.

“I presumed that, in former times, there had been thick ropes running through these to facilitate the journey that we were now undertaking as if we were carnival acrobats. There were dimples and depressions in the rock that might have served as footholds, were one to have such a cable to hang on to.

“Fr. Matteo pointed to the second ledge, which was spaced at a distance equal to the previous leap we had made, though somewhat steeper. However, it was also much broader and longer than the one we stood upon now, meandering in a crazy fashion along the cliffs.

“The friar jumped and (with a waggish bobble of the head) stepped backwards to ensure I did not run into him a second time. I leapt and attained the shelf with ease, breathing a sigh of relief, because the winds here were less sharp (due to a slight infolding of the cliffs).

“Fr. Matteo patted me on the back. ‘Good. Now, hand me that book Father Reuss gave you.’

“‘What for?’ I asked, removing it from my haversack.

“‘Because man cannot serve both God and Mammon.’ He seized it and cast it into the gorge below.

“‘Why did you do that?!’

“‘Because it is weighing you down, both physically and spiritually. It is a vanity you do not need.’

“‘It was worth a great deal of money!’

“‘Yes, it was. And what business does a provincial priest have in possessing a library of such treasures.’ He looked at me cooly. ‘Do you realize that if Father Reuss were to sell some of those books, your village could afford an experienced physician to treat the sick and infirm in accordance with the principles of scientific reasoning? And what about that gem-encrusted Bible he has on the lectern by the window? If it were sold, Mariahilf would not only be able to have a schoolhouse but a university. It is a miser’s hoard, Benedikt. And when Father Reuss dies, his precious books will be sent to Admont Abbey, where they will be pawed over by fat, farting prelates; or sold outright to settle a legacy on an archbishop’s bastard.’

“It pained me to hear him speak so harshly of the man who had been my mentor since I was a boy. I would never tell Fr, Matteo of the Latin primer I carried with me—the first gift Father Reuss ever gave me. I could not bear to lose it as well.

“Fr. Matteo followed the ledge to its end. ‘The last leap is the hardest; for last leaps often are. And you will need a running start.’’ He pointed to a shelf eight feet away and one foot down. It projected less than an arm’s span from the mountain and wrapped around a sharp corner beyond which we could not see. The surface of it was uneven; and, at its bend, it tilted slightly downward toward the abyss.

“My face blanched. I wiped the sweat from my brow. ‘It is impossible for me to make that. I am so scared.’

“‘Don’t be scared. I shall be waiting for you on the other side,’ he said, hiking up the front of his robe. ‘And you don’t make it, you may interpret what I have said figuratively.’

“‘What do you mean?’

“‘About waiting for you on the other side.’

“‘Wait!—’

“He ran, jumped, and landed on the rock. One of the ledges, he had lacerated the soles of his feet. And I saw that they were bloody. He disappeared momentarily around the corner; and then his head and upper chest reappeared.

“‘I have to be out of the way when you jump,’ he explained, ‘or we shall both fall. Do as I did. Leap boldly. Because if you hesitate, well. . . your journey ends here.’

“I had no choice. I removed my haversack and cast it onto the ledge. It landed squarely in the middle of it. And Fr. Matteo stepped out to remove it so that I would not trip on it.

“I took a deep breath, closed my eyes, reopened them, ran and jumped. But when I landed, my boots slipped on his blood; and I was propelled my momentum to the far side of the brink.

“I flung my arms wide. His firm hand seized my sleeve. Desperately I clutched his hand as the ground fell out from under me. My knees struck the rock. I looked up and saw Fr. Matteo grasping a thick iron ring with one hand as he hoisted me up with the other. With our combined strength, I found my footing.

“You did it,’ he said, casually, insensible of the gory footprints he was leaving with every step he took. Brusquely, he turned away and followed a ledge that broadened and led upwards into a complex of vaulted chambers and cells hewn out of the living rock. On all the walls were painted maroon crosses, communion chalices and medieval frescoes of saints. . .”

—“Here it is!” Frau Mattner exclaimed, returning to the table, carrying two plates laden with food. She asked if they needed cutlery or if they had brought their own.

Benedikt told her that he had a knife they could share, but that they would appreciate forks if she had any. She did indeed and removed two from her apron, handing one to each. Sensing they were not in the mood for idle badinage, she left the private room.

Both men were ravenous; and, passing the knife alternately between them, they cut up the schnitzels, and devoured these before consuming the parsley and boiled potatoes. Benedikt leaned around the corner and for Frau Mattner again. When she had reappeared, he asked if they could get a bottle of Mosel, two goblets, and a plate of black bread and cheese.

“Are you paying on credit?” she asked nervously.

Benedikt handed her a Vereinsthaler, which she kissed and put away. “I baked a Christmas torte that yesterday, and you shall have half of it gratis!” A few minutes later, when the wine, the goblets, the cheese and the Christmas torte had been placed on the table, the mistress of the house collected the dirty plates and withdrew.

Hermann poured the wine. “What was this place that Fr. Matteo had brought you to?”

“He told me that it had been inhabited long ago by a sect of Christians known as the Waldensians. Their relationship with Mother Church has always been uneasy. They emerged in the Rhône Valley in the early half of the thirteenth century. But they were persecuted as heretics and fled to the hills of the Piedmont. From there, a band of them sought refuge in the Tyrol and established a thriving community in that alpine aerie over three hundreds years before the founding of Mariahilf am Inn.

“When I had made that final leap, the rocks tore my trousers at the knees; and the blood now seeped into the fabric. Fr. Matteo told me to remove my boots and sit down on a ledge outside, so that he could use the light from the sky to dress the wounds. ‘We must not waste our candles,’ he said. ‘Because we will need them when we leave.’

“‘How did you find out about this place?’ I asked. ‘And where did you learn of its history?’

“He removed a handful of yarrow from his satchel, along with a stone mortar and pestle. As he crushed the vulnerary into a pulp to apply it to my wounds, he spoke in a disinterested voice. ‘I was told of this place over half a century ago by the man whose execution we witnessed in the valley.’

“‘What?!’ I asked.

“He set the pestle aside and stared at me keenly. ‘I was told of this place by the Werewolf of Mariahilf am Inn.’”

—The goblet fell from Hermann’s grasp, for he had fainted away.

Again, a lovely start, Daniel, with the men standing in the starlight sharing a cigarette and having light hearted banter. Then to the pub and more darkly fascinating tales. I love a story within a story within a story. All those lairs add up to make everything more believable and real. It’s the gift of a great storyteller when the characters go somewhere and I wish I was there with them, sharing their food and drink. It shows a world perfectly created and populated by people that seem as real as you and me

Brilliantly done 👍🏼

The story gets ever more fascinating! A large number of interconnected pieces of a closed system have been in motion for a long, long time it seems?