Book II, Chapter 9: The Meeting at the Mill

List of Chapters | Previous Chapter

It was only in recent years that the denizens of the small conglomeration of buildings behind the Eltzbacher Coach Inn had felt the necessity of giving their hamlet a name. They settled on Am Haus Löringhof (Near Löringhof House) in recognition of a heap of rubble in the woods close by, reputed to be the ruins of an ancient castle belonging to the Löringhof dynasty.

The name sounded fancy and conjured up all sorts of romantic associations with Teutonic knights and Merovingian kings. But the main benefit of choosing this name was that it settled an acrimonious dispute that had arisen between Herr Schuster and Herr Mattner, each of whom wanted the town named after his own family, claiming his ancestors (respectively) had been the ones who had tamed the region when it was still “shrubbed up and overrun with Dachse und Waldschnepfen (badgers and woodcocks).”

The matter was put to a referendum, with Frau Eltzbacher voting on behalf of her husband, and “Am Haus Löringhof” won out. But even though the townsfolk were quite satisfied with the designation, the hamlet continued to be identified in chancery records throughout North Rhine and Westphalia as “a small conglomeration of buildings behind the Eltzbacher Coach Inn.”

It was Thursday evening, the night after the remains of the murdered men had been discovered. Hermann was escorting Elischewa Eltzbacher to Am Haus Löringhof for a meeting wtih the aldermen to discuss the matter.

The town was very close to the inn.—“Only a stone’s throw away as the crow flies,” Abner Eltzbacher was fond of saying, blithely mixing his metaphors and speaking in an outmoded form of English that only the occasional American or British traveler lodging at the inn was able to comprehend. Benedikt had explained to Hermann that, as a child, Abner had been educated by a governess from Cornwall, who had inculcated into her charge a variety of quaint English maxims and aphorisms and had urged him to commit to memory thousands of definitions from Dr. Johnson’s voluminous Dictionary of the English Language, which she possessed a two-volume copy of.

Fluffy snowflakes drifted through the mild air that night, as Frau Eltzbacher moved with care over the rutted dirt path that led into the village. Hermann kept one arm within reach in the event she should slip on the ice. At one point, this happened; and he caught her around the waist before she fell. Once her balance had been restored, Frau Eltzbacher thanked him, even though the impertinence of his cavalier embrace had unsettled her. Fortunately, the accident had been witnessed by none but God.

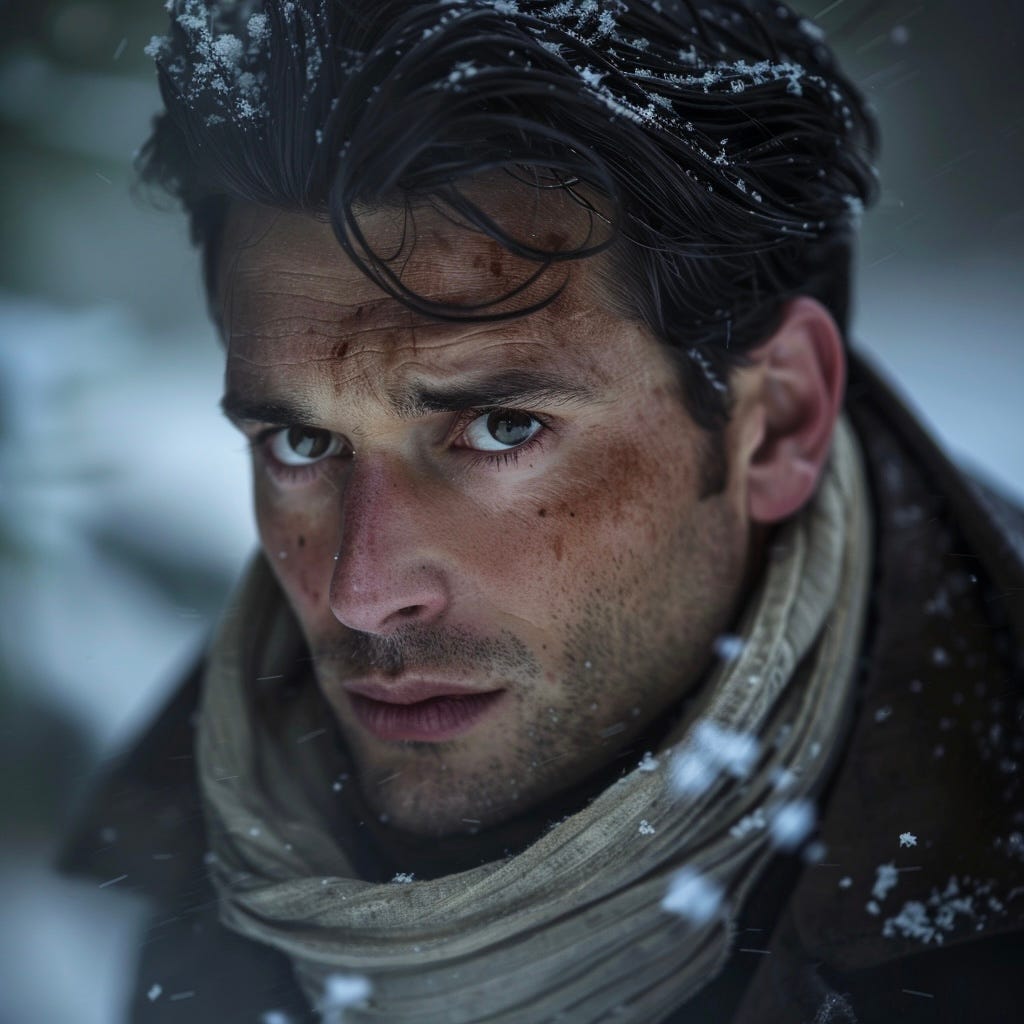

It took Hermann some time to realize that, despite the horrid circumstances surrounding their visit to the village, there was something in his brooding and haggard looks that was attracting the attention of many of the girls and young women along the way. They knew he worked at the inn, but he was hardly ever seen in Am Haus Löringhof, and it was only tonight that they were finally able to see him up close. They studied his profile as he passed. But Elischewa had picked up on what was happening, and her visage darkened until those curious blushing damsels turned away for shame.

As they made their way down the main thoroughfare, Hermann was moved to see the residents’ humble efforts to enrich their children’s memories of the holiday season by setting up a small Christmas market. An old woman sat in a shack, selling gingerbread and marzipan cookies. The doors of all the town’s shops and dwellings were decked out in evergreen; and the streets were ablaze with festive lights.

The religious concord prevailing in the village was such that it was not unusual to see a broad bow-window containing a Protestant nativity scene standing opposite a window adorned with a brass hanukkiah. But although the hanukkiahs were backlit with decorative lamps, they were not lit up. Elischewa explained to Hermann that the reason for this was that their chief candle, the shamash (attendant), could not be kindled until December 18, 1870, the first night of Hanukkah—three days hence.

At Elischewa’s approach, the men touched their hats and the womenfolk curtseyed. They did this in recognition of the fact that their comparative ability to weather the economic storm due to the war with France was because of Am Haus Löringhof’s parasitic relationship with the Eltzbacher Coach Inn, situated as it was on a main highway linking Cologne in the south to the free and Hanseatic city of Hamburg in the north.

Hermann’s home town of Mariahilf am Inn had been about the size of this village, but its residents had been unwashed savages in comparison. Illiteracy had been rampant. There had been no banks. The very concept of advancing credit to foster private ventures had been unheard of. The material comforts so readily available in northern lands had been slow to take hold in the witch-haunted South.

But the whole world has changed since Papa and I emigrated from the Tyrol over twenty-one years ago. I wonder if this is what journalists mean when they speak of a Zeitgeist (Spirit of the Age). Poor Oma could never have conceived of a time when people would send messages across electrified wires, or book passage on carriages crisscrossing Europe on iron rails pulled by machines belching smoke. She would have called such innovations the workings of the Devil and proof positive that the End Times were upon us.

A large tannenbaum decorated with colored yarn, baubles and tiny hooked lanterns stood in the middle of the town square. Children danced and played around it. One mother admonished her son for throwing snowballs at it, warning that if one of these struck a lantern, it could cause a general conflagration.

The most impressive Christmas decoration in the square was viewable at all times of the year. On the tall south wall of the brewery, beneath its pitched roof, was a massive folk mural of Saint Nicholas (patron saint of brewers and children). The figure was represented as he appears in Catholic tradition, crowned with a mitre and surrounded by children. Beneath his feet were panels depicting scenes from the saint’s life, including an obscure one that Hermann doubted anyone else in the town knew.

According to legend, there was a famine in Anatolia; and a wicked butcher murdered three children and chopped up their bodies, storing the flesh in a barrel of brine with the intention of selling it as pork. Saint Nicholas found the barrel and resurrected the children. This was the scene depicted in the panel: three children standing upright in a barrel of brine, fully reconstituted. Perhaps the brine barrels got mixed up with beer barrels and that’s why Saint Nicholas became the patron saint of brewers too.

Hermann could not have been more than four years old when he first heard of “Saint Nicholas and Three Pickled Children.” Oma Ingrid had related it to him on a stormy night, as Papa sat smoking his pipe and listening in. When Oma concluded the tale, she gave Hermann a strip of cured pork and told him it was a piece of one of the children that had been left at the bottom of the barrel. He had burst into tears; and both Papa and Oma laughed. Now, at thirty-two, Hermann found himself smiling at the recollection of his grandmother’s little prank.

He wondered if there was some connection between the barrel in the story and the legends concerning Saint Nicholas’s evil brother, the Krampus, who was said to abduct wicked children and carry them away in a sack, a basket, or a barrel. But as Hermann thought of the Krampus, he was reminded of Papa’s death on Christmas Eve, when the werewolf had manifested itself to him as an apparition wearing a Krampus mask.

Hermann had hardly been able to sleep since being roused shortly after midnight with the news of the massacre. The attack bore the signature of the werewolf. He had tried to maintain his composure and focus on his duties at the hostelry. But with less than three hours of sleep since the revelation, he was at the end of his tether. Once this evening’s meeting concluded, he would have to get some sleep. He burned to spend a private hour with Benedikt so that the ostler could tell him everything he knew.

Somehow he survived the destruction of Mariahilf am Inn. How did this happen? How did he recognize me the moment I arrived? He keeps telling me that he needs time to frame the story before he can relate it to me. What does he mean by that?

The mill was the last building in town, just over the bridge. In late November, the sluices of the millrace had been shut for the season; and the mouth of the canal that diverted water from the Rhine had been dammed up. The wooden cogs and shafts inside had been locked up and immobilized. But the paddles of the great wheel were blanketed in snow and twinkled in the moonlight.

The air inside was cold and foggy, not only from the villagers’ breath but from the steam rising from their cups of warm cider and mulled wine. There were several lanterns shedding light on the scene, along with a larger one that usually swung from a hook near a treacherous bend in the canal but was now depending from the ceiling by a heavy chain.

The mangled corpses of the murdered men had been brought here because the vaulted interior was never heated during the winter; and it was reasoned that this would help keep the bodies refrigerated until they could be buried the next day. On a raised platform at the back of the mill, where the grain was stored to keep it dry, the dead had been laid out side-by-side on low benches.

Hermann noticed that the sheets covering them did not entirely conceal the magnitude of the butchery. The leg of one had been torn from his body and lay parallel to the torso, which caused the fabric to balloon in a ghastly fashion. The coachman had been decapitated; and his head rested between his legs—cheeks wedged between the hobnail boots.

A knot of the children had gathered on the platform to gawk at the cadavers. One girl told her friends that the men’s ghosts had risen up out of their bodies and were now mingling in the rafters with the snow fog and steam from their parents’ hot drinks.

The meeting was about to convene. The children were shooed out of the mill, and the women followed. Elischewa Eltzbacher would be the only member of her sex permitted to stay.

The publican, Herr Mattner, had directed his workers to move the large sofa from his taproom to the mill so that Frau Eltzbacher would have something comfortable to sit on. The old woman found the gesture objectionable (and the sentiment behind it mildly condescending), but she sat on it nonetheless, while the aldermen stood shoulder to shoulder nearby. The only (living) man not standing was Hermann, who found an empty bench against the wall and took a seat, because his knees were killing him. The bench faced the platform on which the corpses lay.

When the women and children had gone and the mill’s double doors had been shut, Herr Schuster brought the meeting to order.

“Thank you for coming,” he began. “Yes, thank you. . .”

Not only was Egon Schuster the Bürgermeister of Am Haus Löringhof, he held the title of magistrate without commission for all the farms and households within a 10 mile radius. His authority as magistrate was limited to “conducting a preliminary investigation when a grievous violation of the law has occurred and reporting the findings of said investigation to an official of greater standing.” But no one had told Herr Schuster who the mysterious “official of greater standing” was to whom he was to report his findings.

Earlier that morning he had visited the scene of the crime where the bodies still lay in situ. He spent an hour averting his eyes from any disagreeable object they chanced to look upon, as he stepped mincingly through the snow like some aristocratic stork, muttering expressions such as “I see,” “unspeakable,” “ah, yes,” “quite dreadful”—all of which (in his mind) seemed appropriate to the occasion and fitting for his role as a magistrate without mandate.

Since the coach was still operable (with none of the wheels damaged), he had wholeheartedly agreed with a halfhearted proposal offered up by one of the bystanders that the coach should be hauled off and stored in Farmer Meyer’s barn. Knowing that the broken strongbox would have to be kept in his possession until he received instructions from the “official of greater standing,” Herr Schuster ordered its coins counted in the open field before he agreed to take charge of it. He did this because he did not want there to be any cause for someone to accuse him of stealing money from a dead banker; or in this case four.

“Thank you for coming,” Herr Schuster repeated. “This is, indeed, a horrible affair. Most horrible. I welcome your advice on how I should proceed.”

“Egon, you idiot,” Herr Mattner interjected.

Herr Schuster cast a rueful glance at the publican and resumed his opening remarks. “I believe this matter technically falls under the purview of the Police Confederation in Cologne. But I’m not sure about this.” He rifled through a sheaf of papers that explained his role as magistrate and laid out all of the responsibilities that he was now trying so desperately to shirk. “But what I do know is that I have no authority in this matter. . .”

Farmer Meyer glanced at Frau Eltzbacher, as if to remind her that it was she who had told him that Herr Schuster would know what to do.

“Gentlemen,” Frau Eltzbacher interposed, “may I speak?”

”Please do,” Herr Schuster replied.

She glasped her gloved hands together. “First, I would like to draw your attention to the fact that the coach under question is a mail packet. I should hope an effort has been made to collect the correspondence that blew out of the bundles.”

Farmer Meyer spoke up. “My sons and I were able to retrieve most of these. We’ve put them back in the mail bags. And they’re currently in the barn with the coach.”

“Excellent,” Elischewa replied. “Herr Schuster, have you considered that the men who attacked the coach were after a letter in one of the bundles?”

The men murmured in approbation, impressed by this subtle line of reasoning which had occurred to none of them. But Hermann knew this was a false lead. This has nothing to do with spies or shilling-shocker mysteries. This was not done by a group of men. It was the work of the demon. But I shall let them think what they will.

Elischewa stood up from the sofa (though she had to rock back and forth twice to do so). “The coach belongs to a firm that operates out of Cronenberg. I have worked with the company for many years. As I understand it, the private papers recovered from the bankers’ bodies clarify who they were and where they lived in Lübeck. The name of their bank was emblazoned on the strongbox.” She lifted her forefinger and turned away from the aldermen, facing the corpses. “Although we could independently notify the families and the companies involved of what has happened, I believe that would be imprudent. . . This affair, Herr Schuster, has nothing to do with the Police Confederation in Cologne. The postal acts of ’67 clearly state that all mail traversing the lands of member states of the North German Confederation fall under the purview of the Prussian Minister-President in Berlin, which is to say Herr Bismarck.”

Herr Schuster groaned. “I have no time to travel to Berlin.”

“I didn’t say you needed to. The Prussians have a garrison in Kohlendorf. Draw up an affidavit describing what has happened. Everyone present will sign it. (I shall sign on behalf of Abner.) And then, in your role as magistrate without commission, you will deliver the document to the Prussian King’s most senior representative in Kohlendorf.”

“And then what?” Herr Mattner asked.

Elischewa’s response was constrained. “And then we wait for further instructions.”

The aldermen exploded into a heated debate, many taking issue with the proposal since they were wary of what might happen if Prussian soldiers entered the town.

Elischewa raised her hands. “I don’t want the military here anymore than you do. But if we attempt to resolve this crisis on our own without alerting the Prussian authorities—and if they were to find out, the consequences could be far graver than any of us can imagine.”

As they talked, Hermann stared fixedly at the coachman’s severed head. It was as if the mouth had begun to grin. To his horror, the eyelids fluttered open and the lips parted. The tongue stuck out. And now the head looked for all the world as if a puppeteer were comically manipulating the dead man’s features. Suddenly, the torso sat up on the bench; and the sheet fell away, revealing a gaping wound stretching from the cadaver’s chest to its belly.

Hermann screamed as he fell forward from the bench. He flung his arms in front of him before hitting the slate floor. It had all been a dream borne of his fatigue. He had fallen asleep for only a few seconds. Farmer Meyer rushed to him and helped him up, as the aldermen looked at him in astonishment and incomprehension.

Frau Eltzbacher knew immediately what had happened. “Please excuse us, gentlemen. He has had a long day.” Elischewa bade the assembly goodnight and left the mill, as Hermann followed her out.

When the proprietress of the Eltzbacher Coach Inn was gone, the aldermen fell into consulted as to who should write up the proposed affidavit. As they talked, they were surprised to hear the sound of splintering wood, followed by a loud crash. The bench supporting the coachman’s body collapsed. The severed head fell from between the corpse’s legs, tumbled off the wooden platform, rolled across the slate floor and bumped into Herr Schuster’s boot.

“Oh dear,” the Bürgermeister said, kicking it away. “I’m glad I’m not superstitious.”

“Well, I am, Egon,” Herr Mattner replied. “And I think a dead man’s head bumping into your boot portends that you will be six feet under by this time next year.”

Everyone laughed, including Herr Schuster, who wagged his finger good-naturedly at his lifelong adversary. But what none of the aldermen present could have predicted was that, exactly one year to the day after their meeting, they would be lowering Egon Schuster’s coffin into his grave as Herr Mattner wept inconsolably and whispered to the men on either side of him that he wished he had never spoken as he had that night at the mill.

Within minutes, Hermann and Frau Eltzbacher turned off the dirt path and crossed the level ground toward the Eltzbacher estate. Elischewa broke the silence.

“Moritz, over the next few weeks some of the village girls will be working with Monika and me at the coach inn.”

“That will help reduce the burden on Benedikt and me as well.”

“Yes. But you are not to speak to any of them. Do I make myself clear?”

Hermann did not quite follow. “What if they need help carrying something, or drawing water from the well?”

“They will not be anywhere near the well; or the stable or carriage house for that matter. I would prefer that, while the girl’s are on my property, you stay out of the coach inn.”

Hermann shook his head. It was obvious what she was implying. But what she said next enraged him.

“Moritz, I must be candid with you. If any of the girls working at the inn should find herself in an unexpected and interesting condition, I am afraid that I will be forced to let you and Florian go.”

“How dare you say that to me! That is the furthest thing from my mind right now.—the furthest thing! I would not jeopardize Walter’s situation for something so stupid as a backroom fuck!”

Frau Eltzbacher stopped at the edge of the yard and frowned. “Who is Walter?”

Hermann could not reply. Tears welled in his eyes. It was over. He had ruined everything for himself and the boy.

The old woman glanced up at the stars. “The night is clear; and the ground here is firm and stable. I no longer need your assistance.”

He placed his hands on his hips and lowered his head.

Elischewa Eltzbacher walked on ten paces and stopped. She turned to face Hermann, but kept her eyes on the snow. “You had every right to be upset with me. My insinuation was crass and uncalled for. You have given me no cause to doubt your integrity. Return to the carriage house and go to sleep. You may rest assured that Florian’s situation has not been jeopardized.”

Question: what does “am Inn” mean? I’m not sure I understand why it’s called “Mariahilf am Inn” - also wondering how you turn on the automatic voice over feature for your stories?

Poor Hermann is just about at his wits end, trying to keep his cover story in tact and protect Walter. All on top of his fear that the Werewolf is already stalking the two of them, and his concern about how the Ostler already knew who he was and where he came from! Talk about stress!! He is lucky to be under the protection of his employer, who seems to be a shrewd and intelligent woman protecting her extended family so to speak.