Book 1, Chapter 5: The Krampus

List of Chapters | Previous Chapter

Friedrich (nicknamed Powder-keg), the barrel-chested man from Innsbruck, had proven true to his word. Friedrich’s son Ludwig handed his uncle the letter vouching for Moritz and Hermann immediately upon their arrival in Cronenberg.

Berthold looked over it, commenting that his brother had already told him in previous epistles that they were coming. He welcomed all three to the Wuppertal (the Valley of the Wupper) and assured Moritz that the wages he paid his men were honorable. Then he smiled at Hermann and said that he, too, would have a place at the factory.

The wheelwright gave Moritz and Hermann a tour of the Landecker Werke, including two exhibition halls in Cronenberg near the river and several workshops and outbuildings in the broad field behind his mansion.

Berthold kept a cordial distance from Moritz and his son when they first arrived, and it was only Ludwig (his nephew) who was permitted to enter the Landeckers’ home. But Moritz quickly proved himself so amiable to the other members of the family, and so instrumental to the company’s sudden uptick in sales, that only three months after they arrived in Cronenberg, Moritz and Hermann were moved from the small brick house behind the large blast furnace to a pair of modest apartments on the upper story of the mansion.

Hermann’s father was so moved by this demonstration of trust and affection that, on the day that Berthold told Moritz of his intent, the poor man crumpled his hat in his hands and burst into tears.

A week after they had been resettled, Berthold invited Moritz and Hermann to sup with the family in the dining room, where he proclaimed that the newcomers were not lodgers but guests, and that they should be treated as family in all but name.

Ludwig Landecker seemed surprised by this, but took it in stride, commenting that, even though he had known little about Moritz and Hermann before setting out from Austria, the two had shown themselves to be faithful and trustworthy traveling companions: “Like dogs a man raises by hand.”

Berthold and his wife Ursula had a daughter named Henrietta, who was only a year older than Hermann. The two became fast friends. And it was no secret that Berthold and Ursula smiled on the prospect of their daughter’s eventual engagement to this well-mannered young boy, a fellow countryman and coreligionist.

Every Sunday, Berthold climbed up into the sprung leather seat of his fiaker, which he himself had designed and built, the only one in the Wupper Valley. The family would mount the coach (which resembled an open landau) and Berthold would drive the household—with the exception of Ludwig—to the neighboring town of Elberfeld, so that they could attend services at the church of St. Laurentius.

In the summer of 1850—a year after Moritz and Hermann arrived in Cronenberg—the household spent a week in Cologne where they participated in events and festivities leading up to the Feast of Corpus Christi. Even Ludwig joined them for this. In later years, Hermann would recall fondly that one special day during that trip when they picnicked with scores of other Catholic families on the banks of the Rhine.

Berthold and Ludwig were good-naturedly laughing at Moritz because he had no last name.

“Moritz,” Berthold said, “I must register you through the Chancery in Cologne. It’s the law.”

“But I don’t have a last name,” Moritz smiled. “I’m just ‘Moritz, son of Augustine’ and my son is ‘Hermann, son of Moritz.’”

Henrietta leaned against her mother and giggled.

Ludwig spat out his Riesling. “That won’t do,” he said. “You’re a woodworker. How about we call you Zimmermann (room-builder) or Schreiner (wood-joiner)?”

“Either is fine with me,” Moritz said. “You choose.”

This set Ursula and Henrietta into hysterics.

“No, no, no,” Berthold said. “The zed at the end of Moritz’s name elides dissonantly with both Zimmermann and Schreiner.”

“I have it!” Ursula interjected. “How about Tischler (table-maker)?”

“Moritz Tischler?” Berthold asked. “I like it!—Moritz Augustine Tischler.”

“Suits me,” Moritz shrugged.

“Tischler it is!” Berthold affirmed.

“I’ve framed houses, built rooms,” Moritz mumbled, smearing lard onto his roll. “I’ve made cabinets, beds, chairs. . . But I’ve never built a table in my life.”

Everyone laughed.

Of course, Papa was lying. He winked at Hermann, who laughed too. Father and son had never been so happy.

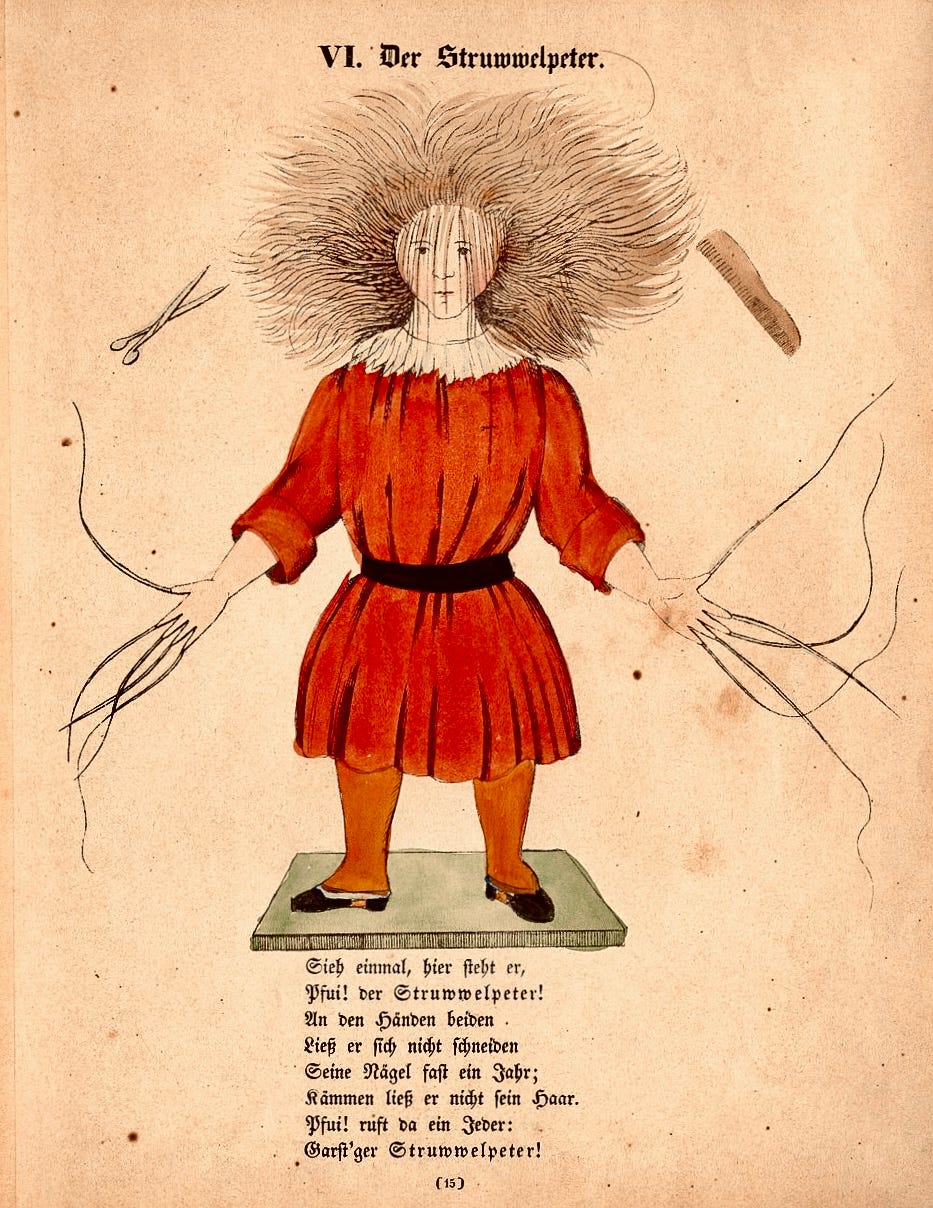

One evening in late November the family was relaxing in the drawing room. Ursula, Moritz, Ludwig and Berthold were playing Skat at the card table. Henrietta sat with Hermann on the couch, teaching him how to read. Hermann was sounding out the words of the children’s book Der Struwwelpeter (Slovenly Peter).

Suddenly, a brick crashed through the hall window. The voices of three young men outside could be heard, shouting: “Ultramontanists! You’re not wanted here! Go back to Austria!”

Moritz ran to the hall and opened the front door. But by the time he made it to the drive, he saw the backs of three youths disappearing into the tree-line. He returned to the mansion and met Ludwig and Berthold in the hall. The three inspected the brick.

The Alsatian maids were on the stairs and upper landing, discussing the matter loudly in that dialect of German that only they understood.

Hermann remained in the drawing room, comforting Henrietta. Only Ursula, the matriarch, remained unperturbed. When her husband returned to the drawing room, she said, “This is undoubtedly due to the unpleasantness in Hesse-Kassel.”

Hermann was too young to understand what this was a reference to. But Ludwig explained to him that Bavaria and Austria were sending troops to Hesse-Kassel to quell an internal uprising there. Prussia did not want Catholic armies so far north, especially Austrians.

Whenever Ludwig spoke of military matters, his eyes took on a faraway look. “The future of the German Confederation,” he said, “hangs in the balance.”

“This has nothing to do with politics!” Berthold fumed, pacing the floor. “This has everything to do with Adolf Goltz and his sons!”

Adolf Goltz was Berthold’s rival and owned a wheelwright factory on the other side of town. To avoid a public scandal Berthold raised a private accusation against Goltz before the civic authorities at the Rathaus. Since both wheelwrights were important to Cronenberg’s economic prosperity, the issue was handled with discretion and the burghers were sworn to secrecy.

After hearing the complaint, Goltz investigated the matter himself, and attended the following day’s session, where he informed the assembly that his son, Franz, had undertaken the outrageous attack against Berthold Landecker’s estate and was its primary instigator.

“I did not grant my son permission to execute so barbarous a deed.” Then he turned to Berthold, hand on the rail, and said, “I apologize to you, Herr Landecker. I can assure you that this will not happen again.”

Berthold waived the financial compensation the assembly voted to him. He asked only that Goltz’s son and co-agitators apologize to him personally and replace the broken window. But in the days after the settlement, Berthold seemed listless and dejected. It was only on Christmas Eve, after having made a private trip to St. Laurentius, that he was able to communicate to the rest of the family why he had been so discomposed.

“In my conscience,” he said, “I believed Adolf Goltz was the éminence grise behind last month’s unpleasantness. I thought this because he is a Protestant and I am a Catholic. But when he apologized to me before our peers, I knew that he was telling the truth.

“I was ashamed for having nourished such a wicked thought and confessed it to Father Brückner. I have been absolved. The penance that has been imposed is for me to admit my error to all of you. And so I apologize for having set such a poor example.”

“Blessed are the ways of the Lord,” Ursula said. “Berthold Landecker, I am proud to call you my husband.”

The following spring, Ludwig announced to his uncle that he would be leaving Cronenberg to join the Prussian army.

“The life of a tradesman is not for me. I want to do something important. I hope I do not seem ungrateful, uncle.”

Berthold asked if old Powder-keg was aware of his intentions to become a soldier. But the young man replied that he had not told his father.

“I don’t understand why you’re leaving,” Berthold said. “But I will not keep you here against your will. However, if my brother asks what has become of you, I shall not lie.”

“I wouldn’t expect you to, Uncle Berthold.”

Hermann married Henrietta when he was fifteen and she sixteen.

“Your grandmother would’ve been proud of you,” Moritz said to his son, as he adjusted Hermann’s cravat on his wedding day. “She might have been alive today had we left Mariahilf earlier.”

“I miss Oma,” Hermann sighed. “And you’re right, she might still be alive. But if we had left earlier, we wouldn’t have come here, Papa. And I would never have met my sweet Henrietta.”

Moritz patted his son’s shoulder and nodded. “You’re a much more dashing groom than I was when I married Ilse.” But no sooner had he uttered Ilse’s name than he turned away, and walked out of the room.

At Berthold’s insistence, the newlyweds remained in the mansion. Moritz and Berthold discussed how to expand the estate to accommodate the young couple and their anticipated offspring. It was decided that a separate house would be added, and that this new building would be linked to the mansion by a gabled cloister. Moritz oversaw its construction.

Charlotte was born first, followed a year later by Frank, whom everyone called Fränkel (Little Frank).

In November 1861, Moritz contracted an infection of the lungs. He told Hermann that it was not serious. But when he coughed there was sometimes blood in his phlegm.

“Papa?”

“I’m fine,” Moritz would say dismissively.

To lighten the mood, Berthold organized a surprise for the family two weeks before Christmas. As the dinner table was being cleared, he rose from his chair and motioned to the maids to remove the candles so that they would not topple.

“I was in town today,” he said, “and I met a man from Innsbruck.”

Moritz squinted and smiled, suspecting a joke. Hermann put his arm on the back of Henrietta’s chair.

Charlotte pointed to her brother, “Fränkel didn’t eat his soup.”

Hermann quoted the poem of Caspar from Der Struwwelpeter: “Ich esse meine Suppe nicht (I’m not eating my soup).”

Henrietta hid her mouth behind her napkin and giggled.

Ursula clicked her tongue. “Charlotte,” she said. “That is very rude of you. Your Opa was speaking.”

“As I was saying. . . ” Berthold resumed. “I met a man from Innsbruck today. And I told him that there were two naughty children living under my roof. And that I feared St Nicholas might not bring them treats this year. Do you know what the man told me, Ursula?”

“I have no idea, Berthold,” his wife remarked with a bewildered smile.

“He told me that in the Tyrol when little children are naughty, they are not visited by St Nicholas, but by his evil brother, the Krampus, who whips them with a birch rod and carries them off in a basket so that he can eat them!”

Suddenly, into the dining room from the hallway stepped a man in a monstrous mask with four horns, wielding a birch rod. He growled as he advanced to the dining room table. Then he smacked the tablecloth with the rod, overturning two of the empty wine glasses.

“Ahhh!” Ursula screamed and covered her face. Little Charlotte and Fränkel leapt from their chairs, shrieking and crying as they clamored under the table and crawled as quickly as they could to Hermann’s legs.

“Papa!” Henrietta shrieked. “Who is this man?!”

“Hello cousin!” Ludwig said, removing the mask. Then he pulled off the robe of sackcloth that covered his Prussian regimentals.

“Ludwig!” Ursula and Henrietta exclaimed.

Charlotte had ceased to scream but was still sniffing and trembling. But Fränkel sobbed and said to Hermann, “I don’t want the devil man to eat me.”

“I’m furloughed until spring,” Ludwig announced. “I just came from Innsbruck, where Papa told me to give Uncle Berthold this holzlarve (wooden mask). He said, ‘Tell my brother I’ve modeled it off his own face as I recall it!’”

Ursula and Henrietta laughed. Berthold touched his breast and feigned offense.

But Hermann looked at his father, whose face was ashen. “These little ones have never heard of the Krampus,” Moritz said, coughing. “You scared them.”

Ludwig set the mask on the dining room table and bent down to the children, arms extended. “It’s alright! You can come out! I’m not going to eat you! We’re related!”

“I don’t like that man,” Charlotte said to Henrietta.

“He’s my cousin, darling.”

Charlotte whispered into Hernrietta’s ear. “He’s not a good man. I can tell.”

But Berthold was groaning and shaking his head apologetically.

“Old friend,” he said to Moritz, “I’m so sorry. I should have told you about this. I thought you would find it funny. I didn’t mean to distress you.”

“It’s fine,” Moritz said, wiping his brow. “But if you don’t mind, I think I’ll turn in for the night . . . Welcome home, Ludwig. It’s good to see you again.”

“It’s good to see you, Herr Tischler.”

The following morning after breakfast, Ludwig and Hermann went down to the buildings in the valley so that Ludwig could see the changes that had been made and so the two of them could catch up on old times.

“I’m attached to the staff of Lieutenant-General von Manteuffel.”

“Who’s he?” Hermann asked.

“Only the most important man in the Prussian army. He’s Catholic and he’s taken a liking to me. I got married a few weeks ago.”

“Why didn’t you tell your uncle?”

Ludwig tilted his head and laughed. “It’s awkward. You see, a Junker’s daughter got knocked up, so I’ve been asked to marry her and raise the bastard as my own. My papers have been forged to make me into a minor blue-blood, which is how I became an officer.”

Hermann turned away, red-faced.

“Anyway, they’ve packed the bitch off to Petersburg until she has the brat, and until enough time’s passed to avoid a scandal.”

“Ludwig!” Hermann shouted. “You will not talk that way while you’re here. I don’t want my children to hear that kind of language. And if I may say so, that is a vile and unchristian way to speak of a woman and her unborn child—especially if you are to be their lord and patriarch.”

“Sorry. I keep forgetting I’m not in the barracks.” Ludwig looked sidelong at Hermann. “You’ve certainly come a long way, haven’t you? My family’s done a lot for you and your father.”

“I’m grateful for everything God has granted us,” Hermann said.

Ursula waved at them from the top of the wooden staircase leading up to the mansion.

“Hermann,” she yelled. “Come!”

“What’s wrong?” Hermann asked.

“It’s your father!”

Hermann and Ludwig sprinted up the staircase. When they reached the mansion, they climbed the narrow steps leading up to Moritz’s private room. Hermann’s father smiled wanly at them as they entered. Berthold and Henrietta stood by the door.

“Come here, son,” Moritz said.

Hermann went to the bed.

“I’m not going to make it to the new year.”

“Don’t say that, Papa.”

“Listen to me. I’ve lived to see you grown up and married. And I’ve dandled two grandchildren on my knee. Few men are so fortunate.”

Hermann wept, and turned to look at Berthold.

“Our friend’s journey is nearing its end. I’ve summoned Father Brückner to administer the Last Rites. The mason, a good friend of mine, will be notified this afternoon that your father is to have a marble headstone. I’ve directed the foreman of the south workshop to have his men prepare a plot in the wooded clearing by the building.”

“Hermann,” Moritz said.

Hermann turned to the bed and wiped the tears from his eyes.

“You know my height, boy. Build my coffin.”

Hermann returned to the workshop where Ludwig helped him build Moritz’s coffin. As Hermann sanded the coffin’s edges, Henrietta appeared at the entrance, standing on the shavings with Fränkel at her side.

“Why’s papa crying?” the boy asked.

“Because, he’s about to lose his own papa.”

On Christmas Eve, Hermann sat at Moritz’s bedside, keeping vigil as his father lay dying. It was just after midnight, and the rest of the family was asleep. The candle on the bed-stand guttered. The image of the Virgin Mary that had served as the headboard of Hermann’s childhood bed hung on the wainscoting opposite the deathbed.

Hermann nodded off but woke moments later because he could no longer hear his father’s breathing. He grabbed the shaving mirror that lay on a shelf close by. It was the same mirror Moritz had brought with him from Mariahilf.

The old man’s skin was clammy and the edges of his mouth and eyes were blue. Hermann lowered his head and put one ear to his father’s chest. He heard nothing. But the glass fogged when he held the mirror over Moritz’s mouth.

It won’t be much longer.

He stood up and stretched—but then froze. Reflected in the window opposite Hermann was a naked man with an erect phallus standing just behind his left shoulder. The man wore the wooden Krampus mask. And beneath his hairy chest dangled the six swollen teats of a nursing she-wolf.

Out of the mask’s jaws slithered a thin and unnaturally long tongue, which began to whip back and forth, like a serpent’s tail.

Hermann exhaled and turned slowly to his left, looking over his left shoulder. But there was nothing there. Suddenly, a hot wet tongue invaded his right ear and licked it.

Hermann cried out in horror, waking the household. Then he heard his father’s death rattle and turned his attention to the bed. The old man’s head rolled to the side and a inhuman voice came from the dying lips, saying: “Mmm. . . Lecker, lecker (yummy, yummy).”

Hermann fainted. When he awoke, he was in his own room and Henrietta was at his side. He did not speak of the horrid vision, attributing it to the shock of his father’s death.

The day after Christmas, Moritz was laid to rest under an oak tree in that clearing near the factory that Berthold had designated.

Hermann could shed no more tears. But his throat tightened when he read the simple inscription on the tall marble headstone:

Moritz Augustine Tischler 1806(?)—25 December 1861 Father to one. Friend to all.

The coffin was still open. Hermann knelt beside it and, under his father’s rigid arms, placed the small wooden figurine that Moritz had carved so many years ago. It was the statue of an old man holding a lantern in one hand and peeling back his skin to reveal his ribs and entrails with the other.

Hermann had only been seven-years-old at the time it was made.

“What is this, Papa?”

“It’s called a memento mori. It reminds us that even in our happiest of moments, Death lingers around the corner.”

Hermann thought of the day in Cologne when he and his father had acquired their last name—Tischler—and how happy they had been. But this wasn’t the only lesson Moritz had built into the figurine.

“Do you see how I made worms inside the man’s belly?”

“Yes,” Hermann said. “What are they for?”

“The worms in the man’s belly are there to teach us that, even though we walk this Earth by the grace of God, we are already dead.”

Hermann rose from the coffin and nodded to the carpenters, who put the lid over it and hammered the coffin shut.

That night, Hermann dreamed that Ludwig Landecker wore the Krampus mask and stood at Moritz’s grave, tapping on the marble headstone with the birch rod. When he woke, he thought he heard the sound of wood clicking on stone.

He got out of bed quietly—so as not to disturb Henrietta—and put on his slippers. He went to the landing. He could still hear the sound coming from outside. He open one of the leaded-glass windows and cocked his ear.

There it was again: click-click clack, click clack-clack. There was no pattern, no rhythm. But it seemed deliberate, like a telegraphed message.

“Papa?”

“Charlotte,” Hermann gasped. “What are you doing out here? Why aren’t you in bed?”

“Fränkel and I dreamed the Krampus was tapping on Opa’s tombstone with a stick.”

Hermann went to his knee and kissed her brow, but his eyes were wide. “You’re both just sad from the funeral. Go back to bed.”

When she was gone, Hermann stood with his palm on the bannister until he heard it again. He returned to the bedroom and strapped on his boots. His overcoat was downstairs.

Henrietta sat up in bed. “Hermann? What are you doing?”

“The door to one of the outbuildings in the valley is open and needs to be shut. It’s blowing in the wind.”

“Can’t it wait till morning?”

“It’s already awakened the children. I’ll be back momentarily.”

He descended the steps in the dark. On the table in the hall was a coal-oil lantern. He removed a box of sulfur matches from the drawer and lit it. His overcoat hung on a hook by the door; he removed it and hung the lamp on the hook as he pulled the coat over his shoulders.

Once outside, he shut the door behind him. Passing under the gabled cloister that connected their building to the old part of the mansion, he reached the cobbled walkway that ran to the back.

He descended the staircase to the field in the valley.

A light dusting of snow covered the ground. In the cool night air the clicking seemed unusually loud. At the base of the steps, Hermann scanned the snowy terrain. He dreaded the prospect of seeing paw prints dimpling the snow. But fortunately there were none. He lifted the lantern.

There it is again! That clicking sound!

It was unremitting, constant—borne on the soughing winds that emanated from the clearing where his father had been interred. Hermann muttered a prayer to Our Lady of Mercy. What would he do if his father’s plot had been dug up? Or obscenely violated?

He passed between the naked trees and shrubs and reached the clearing where the headstone could be seen in the pale moonlight filtering down through the overhanging branches.

The burial mound was blanketed in a thin layer of snow and remained undisturbed. But in the lantern’s light he saw the source of the clicking. Atop the marble headstone, wobbling back and forth on its unsteady base, stood the wooden memento mori.

Great atmosphere and detail, love that you include folklore and fairy tales so aptly! And Krampus is such a powerful myth! The 2015 movie was quite good, too!

That was a very creepy and unsettling ending, Daniel. Made all the better by the calm, placid build up where everything seems normal and unthreatening. But, as with all great scary stories, the horror is never far away

Really wonderfully atmospheric writing. Well done 🐺