The Witch in the Mountain Pass: Chapter 6

A Novel

Saul died for his transgression which he committed against the Lord, even against the word of the Lord, which he kept not, and also for asking counsel of one that had a familiar spirit. (1 Chron. 10:13)

Chapter 6: Whom the Gods Would Destroy They First Make Mad

“The Lord…” Papa Nikolaos said and went silent, his face ashen. He turned and looked at the iconostasis. Then slowly, and in apparent dismay, he paced in a half circle until he faced the congregation again. He seemed at a loss. The citizens of Dagitsidos stood patiently under the high dome of the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God.

The Nazi film director Egon Koebner drew away from the eyepiece of the juddering camera. So long as he kept a canvas-gloved finger on the hot switch, the camera would keep rolling. All Koebner needed for this sequence was a few dramatic and primitive gestures from the priest—two minutes, tops. He would hire actors in Berlin to dress as Greeks and smear dirt on their faces. Then he would edit them into this sequence, show them reacting like animals in a zoo to the priest’s sermon.

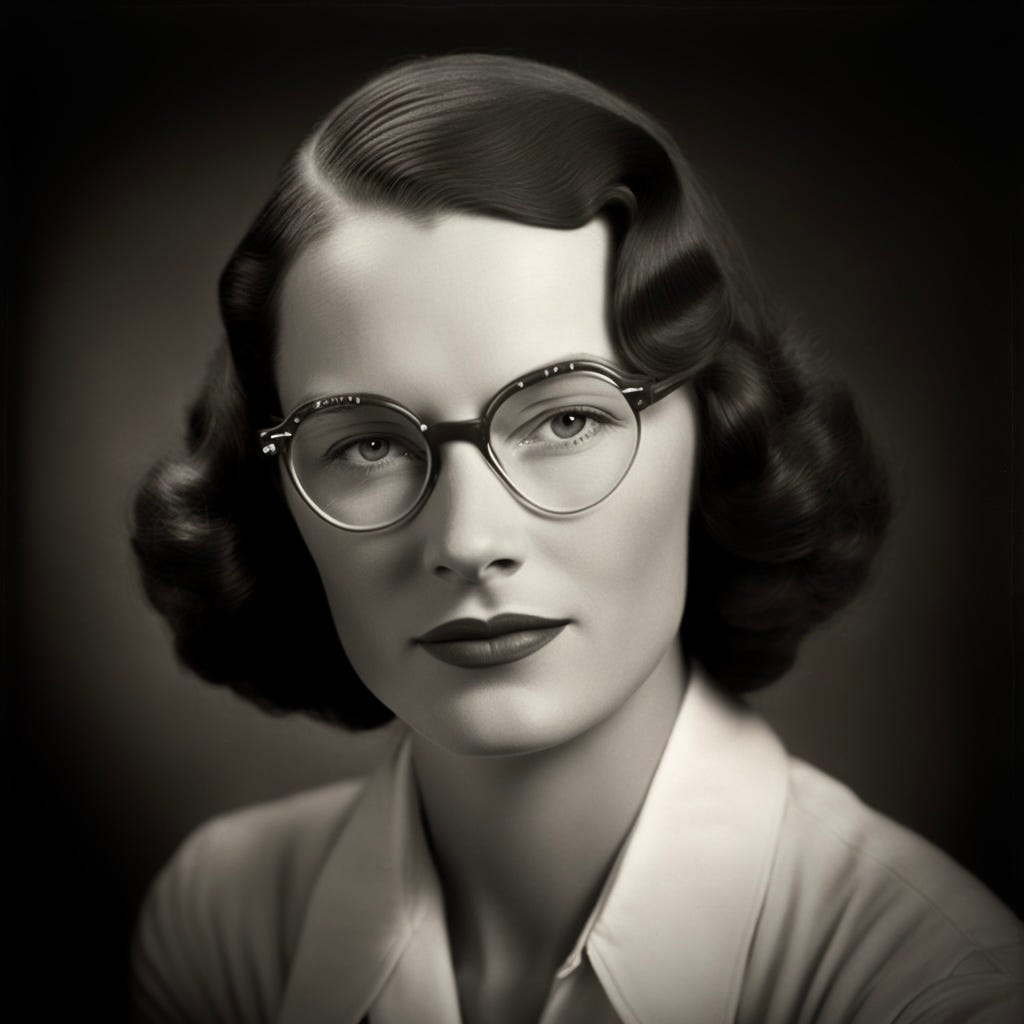

Koebner leaned over to Thekla Witte, the half Greek, half German anthropologist in spectacles who had flown to Greece with him: “Why did he stop talking?”

Thekla shrugged. The director emitted a sigh and peered again through the camera’s eyepiece.

The young diplomat Günther Rippenberg was crawling on the floor, adjusting the cables linking the two trunk-sized batteries to the camera and the collapsible lamp stands set up around the narthex. Reflective screens were rigged up behind the bulbs to intensify the lighting. The men of Dagitsidos had helped set everything up. The church was inherently and quite stubbornly dim, but the artificial lighting had made the interior brighter than anyone in town had ever remembered seeing it before.

It was a Wednesday morning in late September, 1934. Uncle Spiro, whose mansion the Nazis were staying in, had sent two boys around town to all the households at the crack of dawn. He had ordered the villagers to dress as if it were Sunday and assemble in the church by noon. There was nothing the townsfolk could do but go along with it, since Papa Nikolaos had endorsed the directive.

Koebner had originally proposed filming the sermon on Sunday, but Papa Nikolaos explained to Thekla that filming in the church on either the Sabbath or the Lord’s Day was strictly prohibited.

Papa Nikolaos now drew himself up to his full height and looked balefully at the camera. “The Lord,” he repeated in a frigid, commanding voice, “abandoned Saul.”

Mama Irene gasped. She’d never heard Papa Nikolaos speak so forcefully.

The priest continued: “Saul was the Lord’s anointed. In his youth, he was beloved by God. He was the chosen one! Saul had banished from Israel all false prophets, all idolators. He had put to death the gibbering witches and unholy wizards. But when the Philistines rose up against him, the Lord went silent!” Papa Nikolaos lifted his index finger to his lips. He waited until no sound could be heard in the church but the rattling of the camera and Uncle Spiro’s nervous cough.

“The Lord no longer spoke to Saul,” the priest lamented, looking at the director over his shoulder, “neither by dreams, nor by prophecy, nor by the Urim.” The way Papa Nikolaos had uttered the word “Urim” made Mama Irene clutch her breast and swoon. She had no idea what an “Urim” was, but was very upset that it had stopped talking to Saul.

Koebner suspected the priest was under the impression his sermon was being preserved for posterity. Maybe that was why he was hamming it up. But the director had opted not to record sound for this sequence. These pauses of the priest’s, he thought, won’t do; they’re too long.

“When the Philistines rose up against the House of Saul,” the priest continued, “the King fled into the wilderness, like a coward, like a guilty man, for the guilty flee when no man pursueth! Into the Valley of Jezreel, Saul fled—even to the Canaanite city of Endor, so that he might consult a weird woman, a witch, who lived secluded among the rocks.”

Thekla looked at the back of the church. A woman in a hooded black robe with a veil over her face knelt before an ancient icon representing the Dormition of the Mother of God. A braided rope was tied around the woman’s waist. She seemed to sense someone was looking at her, because her neck inclined slightly in Thekla’s direction. The woman rose from the ground. Thekla turned away.

“The King was in disguise, muffled up in a cloak, side-eying the witch, who stood behind a smoldering hearth. The Witch of Endor welcomed him.—‘Use your familiar spirit,’ the King said, ‘to raise up the man whom I shall name to thee.’ But the old woman suspected a trap. ‘Do you not know,’ she said, ‘that Saul has ordered the likes of me put to death for using witchcraft?’—‘I swear by the Lord,’ Saul said, ‘that no punishment shall befall thee.’—‘Whom shall I raise up?’—‘The Prophet Samuel!’ Saul replied.”

Clio was getting bored. The girl sighed and folded her arms. Mama Irene saw her slouch. She nudged her and told her to stand up straight. Clio scratched her ear and rolled her eyes. Then she noticed that the German man on the floor was looking over at her. He grinned and winked. She turned to look at her mother to see if she’d seen what the man was doing, but Mama Irene was listening with rapt attention to the sermon.

Thekla saw Günther staring wolfishly at the girl, who couldn’t have been older than thirteen. “Schweinhund!” she hissed. Günther heard her, but the director apparently hadn’t. Now Thekla was disgusted, not only with him but with herself. Last night, after their arrival in Dagitsidos, and after Uncle Spiro had shown them to their rooms, she snuck into Günther’s room. They made love against the wall because the wooden bed frames were inconveniently creaky. They vowed to keep their encounter a secret. They had to. It could have affected both of their careers. The suddenness and unexpectedness of the sex, the intensity of it all had excited her, eased her initial misgivings about being blackmailed into making this trip. But now she was appalled by what she’d done, and frankly worried. What if Günther tried something scandalous? Caused a gdikiomόs (blood feud)? She composed herself so the congregants didn’t notice that she was flushed and angry. Leaning down, she whispered into Günther’s ear, “We are not in the slums of Wedding. If you aren’t careful, you’re going to get yourself, or all of us, killed.”

Günther frowned, rose from the ground, and walked over to one of the lamps.

Papa Nikolaos raised his arms: “When the witch saw the shade of Samuel, she knew that the man who had consulted her was Saul in disguise! ‘Why did you deceive me!’ she cried out. ‘Be not afraid,’ Saul said, ‘but tell me what you saw.’—‘I saw gods rising out of the earth and an old man among them who was covered with a mantle.’ Then the ghost of Samuel rose up out of the witch’s hearth.”

The witch in the mountain pass heard Papa Nikolaos’s sermon, even though she was not there. She walked out of the empty taverna and down toward the cave. “Why have you raised me up!” she said to herself, smiling.

The ghost of Yiayia Elena emerged from the cave’s darkness. She wore an Albanian headscarf with coins sewn into the edges. “The Lord has abandoned me,” Elena said. “He speaks not to me, neither by dreams, nor by prophecy, nor by the Urim.” The bronze fragments dangling from the oak branch over the mouth of the cave made a tinkling noise, which mingled with the cooing of the doves on the ledges.

Papa Nikolaos shouted: “‘WHY have you consulted me?!’ the ghost of Samuel asked, ‘seeing that the Lord has abandoned thee and has become thine enemy!”

Papa Nikolaos wiped his brow, exhausted. He fell silent again.

Koebner was impressed by the performance. He had no idea what the man was ranting and raving about but it didn’t matter. When it came to making movies, spectacle trumped language: flashes, flares, and fireworks, that was where the money was.

The baker leaned over to Uncle Costa. “Why does that machine make a rattling sound?” he asked.

“It creates moving pictures,” the swineherd replied.

“Why would anyone want moving pictures? I can’t chase pictures at my age.”

“No,” Uncle Costa said. “The things inside the pictures move.”

“Dear God, that’s the Devil’s work,” the baker said and crossed himself.

“The Lord had driven Saul mad,” Papa Nikolaos said, wagging his finger at the camera while looking at the floor. “Saul was no longer capable of recognizing that what he was doing was a sin. Evil had become good in his eyes. He had gone against the dictates of the Lord, which is to say that he had consulted the Witch of Endor instead of killing her.”

Papa Nikolaos looked up and shrugged in an exculpatory fashion. He didn’t want to be misunderstood. “I’m not implying that the justice meted out in the time of King Saul is applicable today.” He pointed to the north side of the church, in the direction of the mountain pass. Then he spoke rapidly in the Epirote dialect: “But we—here!—in Dagitsidos have a witch living in our midst!—A witch, who’s been welcomed with open arms, who’s been accorded all the rights and benefits of a citizen of this town!”

Mama Irene touched her brow with both hands because now she understood the point of the sermon. She turned and looked at Cora, Sofia, and Agatha in alarm. The men and women started groaning and crossing themselves. They’d been hoodwinked into welcoming the witch into Dagitsidos, and now she was living among them as a friend and confidant!

Suddenly, all eyes fell on Papa Nikolaos because he was foaming at the mouth. He seized the kalimavkion on his head and threw it to the ground. Then he tore open his robe. His face was red. He cried out “Ahhh!” and collapsed. Manolios and Uncle Costa rushed to his aid, as the Nazi director said “Cut!” in German, which none of the Greeks understood. They thought he was urging someone to help the priest.

Now all the congregants, including little Clio, began to cry and wring their hands, because they’d angered God so much that he’d given Papa Nikolaos a stroke.

“How could we have been so stupid,” Agatha mumbled dejectedly, reaching into the pocket of her dress to make sure her clay pipe was there. She’d need a smoke after this.

“Get off me!” Papa Nikolaos shouted, pushing Uncle Costa and Manolios away. Then he rose and dusted himself off. He told Thekla to ask the film director if he wanted him to deliver the sermon again, because he had an extra cassock in the residence. The congregants were confused but relieved he was unharmed.

“Tell him that won’t be necessary,” Koebner said, looking at Manolios in a strange way. Thekla translated. She had no sooner finished when Koebner said, “Ask the priest if there’s someplace in town with a bare whitewashed wall… Tell him I want to film that young man with the harelip.”

“What?” Thekla asked.

“The boy over there,” Koebner said, pointing at Manolios. “I want to film him.”

Thekla translated what Koebner had said. Manolios heard what Thekla was saying. He looked at the director, then at Dorcas.

“I don’t understand,” Dorcas said quietly. Somehow her baby Tobias was still asleep in her arms.

Thekla deduced that Dorcas was the wife of the man Koebner was referring to. “He would like to film your husband. What’s his name?”

“His name is Manolios,” Dorcas said.

“The director needs a place with a plain white wall so he can film Manolios in front of it.”

Papa Nikolaos interjected, “Of course you can film him. He’d be honored. The barber has a spacious shop at the bottom of the hill. The shop has a plaster wall. You’ll be able to set up your equipment inside.”

Koebner waved his arms expansively. “We won’t need much equipment for this. I’ll just need the camera, one battery—and that lamp stand over there.”

Papa Nikolaos signaled for the barber to come to him so that he could explain the situation. Günther heard Koebner’s directions and started disassembling the camera. Günther asked Uncle Costa, Manolios and his father, Loukos, to help carry the battery and cabling, and to retrieve the lamp stand that the director had pointed to. Günther said he’d carry the camera himself.

“I can collect the rest of the equipment later,” Günther said. Thekla translated.

As the townsfolk filed out of the church, the men who were helping carry the equipment shouted for everyone to get out of the way. Papa Nikolaos said that, since the filming in the church was done, he would stay behind.

Thekla wondered why no one was commenting on the veiled woman at the back of the church. She must be an ascetic or a leper. It was strange Koebner had shown no interest her. She was just the sort of oddity Thekla would’ve expected him to want to capture in celluloid.

Once the electricity was shut off, the church was plunged into its customary gloom. The guttering candles in the tin sand troughs, which had been burning throughout the filming, now shone in dim counterpoint to the garishness of the artificial light.

Thekla stepped outside into the bright day. She walked with the townsfolk up the steps. There was a general feeling of excitement. No one in Dagitsidos had ever seen a film crew. In fact, only a handful of the townsfolk had ever seen a film. Thekla overheard them talking about it. It was only Spyridon, the Nazis’ pompous host, whom everyone called “Uncle Spiro,” who appeared to have a grasp on the potential for profitability in the moviemaking industry. He had asked a few pointed questions about the camera, how hard it was to use, the cost of maintaining it, etc. He seemed to have intuited that filmmaking was a business like any other, with its outlays and expected monetary returns.

At the top of the steps Thekla joined the crowd heading down the hill into town. There were people already milling about in the town square in front of the barbershop. The barber had hauled the single chair out of his shop in order to make room for the filming.

Uncle Spiro became imperious and yelled at the townsfolk loitering about, telling them they needed to stand well enough away because the barbershop could only accommodate a few people; and that the director would not be able to film if everyone was crowded behind him.

“Also,” Uncle Spiro added, cupping his hands around his mouth, “keep you feet off the ropes that are nourishing the machines with electricity, or they’ll become exhausted. If the ropes get tired, the director will have to go back to the church and fetch the ropes he left there. And that will take time.”

Inside the shop, the director set a small wooden stool against the cracked whitewashed wall. Günther assembled the camera. He then ran a cable from the battery to it and a second cable from the battery to the collapsible lampstand with its single electric bulb.

“Fräulein Witte!” Koebner exclaimed.

“Ja wohl, Herr Direktor?” Thekla said as she stepped into the shop.

“Could you ask them if anyone has a petrol lamp that they could strike up?”

Thekla went back outside and relayed Koebner’s request to Uncle Spiro, who nodded and told Uncle Costa to take charge of the request.

“Fräulein Witte!” Koebner said again.

Thekla rolled her eyes and went back inside.

“Where’s the harelip?”

Manolios was standing in the square holding Tobias. He’d taken the baby from Dorcas because Tobias was wide awake and fussing. Dorcas needed to rest her arms. She’d been holding the baby for two hours.

Thekla went to Manolios. Her smile was brittle. “Are you ready?” she asked.

“Give Tobias to me,” Mama Irene said. “I can hold him.”

Manolios kissed the baby’s brow and handed him to Mama Irene. Then he looked at Dorcas.

“You don’t have to do this,” Dorcas said. Manolios’s father, Loukos, echoed her words.

“Manolios!” Uncle Spiro shouted. “Get over here! They’re waiting!”

Manolios entered the barbershop. The three Germans were inside. Dorcas went to the door. Uncle Spiro huffed and tried to push her out of the way. But she elbowed him, so he relented, grumbled, and stood behind her.

“Take off your shirt,” Koebner said. Thekla translated this into Greek.

Manolios told Thekla that he didn’t understand. She repeated the director’s request. Manolios loosened the laces of his shirt and pulled it off over his head. The barber came into the shop with a lighted kerosene lamp, and handed it to Günther.

“What do you want me to do with this?” Günther asked Koebner.

“I’ll tell you in a moment,” the director said, feeding the celluloid film into the projector and then clapping the covering shut.

“Sit down on that stool,” Koebner said. Thekla repeated the command in Greek.

Manolios sat down, back to the wall.

“Very nice,” Koebner said. He went to Manolios and grabbed his chin. He then made a few rambling comments that Thekla had trouble hearing, but which she translated: “Now, keep your chin up, like this, but thrust your shoulders forward… like I’m doing.”

Manolios did as Thekla said. The director grabbed Manolios’s shoulder and said, “No, thrust them out more… So that you look weaker, so your chest looks more concave and sunken.”

Manolios had been looking at Dorcas as Thekla translated. He was embarrassed and confused.

“I assume he’s mentally retarded as well?” Koebner asked.

“I don’t know,” Thekla replied.

Koebner sighed and went back to the camera. “Now, Herr Rippenberg, I want you to hold the petrol lamp to the side of his face and lower it so that the shadows are augmented. The effect will make him look more brutish. And then when I signal for you to move, you’ll walk to the other side to do this along the other side of his face as well.”

Günther nodded.

“Right. One, two, aaaand, action.” The camera began to roll. Manolios stared dully at the lens as Günther manipulated the flickering lamp as Koebner had instructed him to do. The shadows cut across Manolios’s face, making his cleft lip more pronounced, distorting his hollow chest so that he looked undernourished.

Two boys had climbed up on the bench outside the barbershop and were looking in through the open window. They laughed, and one said loudly, “He’s making Manolios look like a monster.”

A tear rolled down Manolios’s cheek.

“You see,” Koebner said, from behind the camera, “he’s unhappy. The cruelty of our generation is that wretches like this are forced to live on, when all they want is peace and release from their suffering.”

When the ghost of Yiayia Elena saw how her grandson was being mistreated, she covered her eyes and flew into the clouds, howling in grief.

“Move the lamp to the other side of his face,” Koebner said.

Manolios sneered as Günther passed in front of him. He watched the Nazi take up his position on his other side. Manolios wiped the tear from his face. He could hear Tobias crying in the square outside.

“Ahhh, I’ve caught the creature’s resentment,” Koebner said triumphantly. Then the director addressed Günther: “He looked positively devilish when you stepped in front of him, as if he wanted nothing more than to kill you.”

“No,” Dorcas said quietly in English, stepping into the room. “No,” she repeated, tugging Thekla’s blouse.

“The wife would like you to stop,” Thekla observed.

Koebner ignored her. Manolios rose from the stool, grabbed his shirt, and took Dorcas’s arm. The couple walked out of the barbershop. Mama Irene went to them and handed Tobias to Dorcas.

“Where is he going?!” Koebner shouted. “I wasn’t done!”

Uncle Spiro shook his fist at Manolios but knew that the boy wouldn’t come back. “We have other ugly people in our town!” Uncle Spiro told the director. “There’s the baker. He’s very, very fat. He’d love to be filmed!”

Thekla translated Uncle Spiro’s remarks but Koebner had lost interest. He told Thekla he was done filming for the day. He turned off the camera and told Günther to pack up the equipment and have everything moved back to Uncle Spiro’s mansion, including the lights and batteries they’d left in the church.

Orders were given to the men to assist. Loukos went back to the church to oversee the dismantling of the lights. Manolios didn’t participate. He took Tobias from Dorcas and walk with her to their home.

Uncle Spiro was agitated. He wasn’t sure what the Germans were talking about, but he was worried that Manolios’s behavior had soured the visitors’ experience. It could reflect poorly on him as their host. The diplomat had paid him handsomely to ensure their needs were taken care of.

“Spyridon!” Uncle Costa cried out from the river.

Uncle Spiro told Thekla to tell the director that he would be back in a moment.

He walked down to join Uncle Costa. A large leaky raft had just arrived in town. The crew was securing it to the iron rings at the side of the jetty. A lean-to took up a quarter of the raft’s surface. Three men in red fezzes with tassels disembarked. There were prayer rugs and blankets rolled up and stored under the lean-to. The raft was free of cargo. Once Spyridon made it to the jetty, Uncle Costa walked back up to the town square.

Thekla was curious. She left Günther and Koebner so she could see what was going on.

“Kareem Abu Shahed, my friend!… Salam and so forth!” Uncle Spiro said.

The leader of the Albanians nodded.

“I’m afraid you’re early. The almonds and olives are still being packed.”

“We’re not in a hurry,” Kareem said, speaking Greek with an accent.

“That’s good!” Uncle Spiro said, jovially. “The sacks and bales won’t be ready until Monday or Tuesday. I’ll make sure you’re provided for: fed and whatnot. But I have guests staying with me this go-around, so you can’t sleep in the mansion like last time. However, you’re welcome to camp anywhere in town—except near the church, of course.”

“We’ll sleep on the boat,” Kareem said.

“No one is going to harm you in Dagitsidos simply because you’re heathens. You’re here under my protection!”

“We’ll sleep on the boat,” the leader repeated.

“Very good,” Uncle Spiro said with a disinterested shrug. “Any news from Parga?”

“No,” Kareem remarked. “But in Glyki the telegrapher gave me a letter and said it was for your Gjermane guests.”

“Ah,” Uncle Spiro said, snatching the letter out of the man’s hand. “Yes, the Germans. I’ll make sure they get it. Well, enjoy your stay. I’ll be in touch.” He walked away.

“Spiro!” Kareem shouted.

“What?” Spiro asked, wheeling around.

“It’s only right you pay me for the letter.”

“God!” Spiro said in exasperation and reached into the pocket of his breeches, removing a drachma. Kareem clicked his tongue in disgust, so Uncle Spiro gave him a second drachma. The coins were grudgingly accepted. Kareem clicked the drachmae together to make sure they didn’t bend.

Uncle Spiro went to Thekla and gave her the letter.

“This is for you, or one of your colleagues,” he said. Then he went to Koebner, since Koebner was obviously the person in charge and it wouldn’t do for him to be left alone too long. Uncle Spiro didn’t know German, but he was adept at spontaneous sign language and getting his point across through pantomime and exaggerated facial expressions.

Thekla looked at the envelope. A blue seal, the insignia of the telegraphy office in Glyki, was stamped on it. It was addressed to “The Germans.” Thekla saw out of the corner of her eye that Günther was walking toward her. Did he seriously think he could charm his way back into her affection?

She handed him the letter. “I assume this is for you or Koebner,” she said.

“Did those gypsies bring it with them?” Günther asked.

“They’re not gypsies,” Thekla said, turning away irritably. “They’re Albanian Muslims.”

Uncle Spiro had exerted a great deal of effort to impress his guests. He had moved the oval portrait of his ancestor, Odysseus Andhroutsos, from its hallowed place over his bed to the top of the staircase landing the day before the Germans arrived. Last night, as he was conducting exhausted guests to their rooms, he paused on the landing and commented on the portrait. This would be the film crew’s second night in Dagitsidos and Uncle Spiro was planning a lavish dinner. He had personally spread the white linen cloth over the long magnificent wooden table which his father had commissioned in Romania in the late 19th century.

Papa Nikolaos had asked Mama Irene and Sofia to volunteer their time at Uncle Spiro’s mansion, preparing the meal for the guests. Mama Irene had eagerly accepted, since Papa Nikolaos rarely asked her for a favor. She wondered if this was a new development in her relationship with the priest.

After the filming earlier that day, Irene and Sofia had bent their steps to Uncle Spiro’s mansion and spent four hours working on the meal. Irene brought Clio along. Sofia and Clio helped Uncle Spiro set the table, as Mama Irene prepared the meal.

“What side of the plate do the forks and the knives go on?” Sofia asked Uncle Spiro.

“I don’t know,” Uncle Spiro said. “It doesn’t matter… ” Then he had an idea. “Put them on the right side of the plate. I’ll tell them it’s an Epirote custom to keep the knife and fork on the right side, since Judas Iscariot was left-handed.”

“What about the spoons? Do the spoons go on the table?”

“Of course not! You put the spoons in the soup bowl! Otherwise they’ll think they’re supposed to sip the soup from the bowls like barbarians!”

When the places were set, the guests’ footsteps could be heard on the staircase. Uncle Spiro told Sofia and Clio to go back into the kitchen. Then he struck a match and lit the candelabra in the center of the table.

“Kaló apógevma,” Günther said as he entered the room.

“Kaló apógevma,” Uncle Spiro replied with a broad grin. He led Günther to his chair.

Uncle Spiro was adamant that the director should sit at the opposite head of the table (“the place of honor”). Thekla took the remaining seat and allowed Uncle Spiro to push in her chair, which he did ineptly and pressed her against the edge of the table.

“Now that we’re all comfortable,” he announced, “we shall eat.”

A plate of olives, sliced tomatoes, and cucumbers was brought out by Sofia who asked who wanted to have the plate first. Uncle Spiro pointed to the director, who took it and removed a couple of olives before passing the plate to Günther.

There was no formality to the meal, no specific ordering of the courses. Everything was brought out when it was ready. The men were served before Thekla. The main course was a baked hen, with a side of grilled potatoes and onions. This was accompanied by a soup of chicken broth with dumplings in it. Mama Irene had never heard of a dumpling. Sofia explained what they were and volunteered to make them. Sofia’s dead mother, who had worked as a kitchen scullion for a Habsburg baron on the Croatian island of Hvar, taught Sofia how to make dumplings when she was a little girl.

“They’re not hard to make,” Sofia assured Mama Irene. “You just squish dough together until it’s packed up into a ball the size of a goiter. Germans love them.” The dumplings were undercooked and didn’t hold together in the broth. The soup looked like a buttery porridge by the time Mama Irene ladled it into the bowls. She sensed this wasn’t the way the dumplings were supposed to look, but it was too late now. Mama Irene remained in the kitchen the entire evening. Clio and Sofia served the guests.

It began to rain outside. There was a faint rumble of thunder. The host spoke rapidly with his mouth full of food. He tore the chicken with his hands.

The conversation, both before and during the meal, was tedious. Thekla hardly had a chance to eat, since she was so busy translating the torrent of inconsequentialities pouring out of Uncle Spiro’s mouth.

Thekla cut a medallion or two from the half-breast of the hen but left the drumstick and wing untouched, Uncle Spiro asked if she was going to eat the wings and legs, because those were the best part of the bird; and, when Thekla said that she was full, Uncle Spiro reached over and took her plate from her so that he could finish the chicken.

As the night wore on, Thekla began abbreviating Uncle Spiro’s anecdotes, which became progressively slurred as he kept filling his pewter cup with ouzo from a carboy at his elbow. He didn’t offer to share the ouzo with the guests. But he had managed to procure two bottles of Cypriot wine and the Nazis drank from goblets of Bohemian crystal.

The ghost of Yiayia Elena floated high in the rafters high overhead, looking down on the scene. She stared fixedly at the filmmaker, the man who had humiliated her grandson Manolios. As she recalled what the man had done, a tear fell from her eye and landed in the film director’s goblet with a plop.

“Your roof is leaky,” the director said.

Thekla translated. “Yes,” Uncle Spiro said, looking up into the rafters. Impossible, he thought. There’s an entire floor overhead and no plumbing in the house. He had no idea where the droplet of water had come from. He relapsed into silence, since the phenomenon didn’t interest him. He poured himself another ouzo.

Egon Koebner spoke: “What were the contents of the telegram you received?”

“It was from the Mission in Athens,” Günther said. “It reported that there are two spare trunk-sized batteries and more lights available in Glyki. I’ll need to fetch them tomorrow or this weekend.”

“I don’t need them,” Koebner said.

“I’ll have to fetch them nevertheless. They’re the property of the Reich. The Embassy has directed me to take charge of them.”

“I don’t plan on staying here beyond the weekend.”

“But Herr Direktor!… ” Günther said, looking nervously at Thekla who was pleased to see him squirm. “Herr Direktor,” he repeated, “you’re scheduled to be in Dagitsidos for three weeks.”

“I nearly have all the footage I need. I can recreate this town and make everything even more repulsive in the Ministry’s studios in Berlin. Maybe a few more scenes of village life. Then I’ll film the witch. After that, I want to leave.”

Uncle Spiro was studying their lips and demeanor. He gathered that they were discussing the letter Kareem had brought from Glyki. The film director seemed to dislike Dagitsidos. This worried Uncle Spiro. He wanted to maintain good relations with the Germans, because the gossip in Epirus was that the Germans were going to be expanding trade throughout the Mediterranean. He had even heard rumors that the German engineers were planning to construct a railroad from Istanbul to Baghdad. He wanted to find out if he could be a shareholder in that.

Thekla spoke up, “Herr Direktor, why didn’t you film the raft on the water today?”

“I have one camera!” Koebner snapped, brushing the question aside. “I can’t afford to have it damaged by water!” Then he turned back to Günther. “Who in the Devil told you that I wanted to be here for three weeks?”

“No one told me. It’s a matter of practicalities… ” Günther said. “Logistics, Herr Direktor.”

There was a loud clap of thunder, and Koebner pointed in the direction of the front door. “Obviously, we won’t be filming tomorrow, even if this weather clears up.”

Uncle Spiro knew that they were talking about the weather and told Thekla frantically: “Tell him that it won’t be raining tomorrow, because I looked at the clouds this afternoon. It’ll be fine. Maybe a few drops before sunrise, but that’s it.”

Thekla translated this to Koebner, who seemed unimpressed.

Günther asked Uncle Spiro, “How long does it take to walk to Glyki from here?”

Thekla translated. Uncle Spiro said, “When I was a young man, I could walk to Glyki in the time it took me to smoke four or five cigarettes.”

Thekla translated.

“But how long is that in hours?!” Günther asked.

“I’m not sure,” Spiro said once the question was translated. The host looked abstractly at the antique grandfather clock in the corner of the dining room, which had no gears or cogs inside of it. He had bought it solely for its understated elegance.

“I hate this place,” Koebner said, looking at his plate. “I want to leave this coming Monday.”

“How?” Günther asked.

“Send a telegram tonight!” he shouted. “Tell them to have a plane ready on Monday to take us back to Berlin!”

Günther swallowed and said, “There’s no telegraph office here. I have to send the message from Glyki.” Günther looked at Thekla.

Thekla told Uncle Spiro in Greek, “My colleague needs to send a telegram from Glyki. Can someone take him there tomorrow?”

“Yes,” Uncle Spiro said, “but the problem is that the telegraph office is run by a man named Tigran, an Armenian. He also runs the telegraphy office and telephone exchange in Parga. He’s the only one in Epirus outside of Ioannina who knows how to operate the machines. Most of his business is in Parga. He only goes to the telegraphy office in Glyki on Wednesday.”

Thekla translated this into German. Koebner touched his brow and sighed.

Günther took a sip from his goblet. “This wine is shit,” he said. There was a long silence. Günther looked over and saw Clio standing at the threshold of the kitchen. He puckered his lips and winked at the girl. Clio was taken aback. She looked at Thekla, who made a subtle motion with her head for the girl to go back into the kitchen. Günther saw what Thekla had done and grimaced. He ran his hand through his blond hair.

The ghost of Yiayia Elena drew her lips back in a sneer. She saw the young Nazi stretch his arms and lean back in his chair.

Günther yawned and looked up at the ceiling. Then he froze in horror. The corpse of an old woman in a black death shroud had been tied up in the rafters. Her rotting head was dangling over his own.

“Ahhh!” Günther sprang from his chair.

“What’s wrong!” Koebner said, rising from his seat. Thekla was too startled to move. Günther pointed up. But now he couldn’t see anything overhead. But in the thickness of the shadows something was unfolding.

“What is that noise?” Thekla asked Uncle Spiro.

The host shrugged and squinted his eyes, trying to see what it was. Then he stood up. As Uncle Spiro’s chair scraped across the floor, the fluttering form of a black dove plunged from the rafters, overturning the candelabra and flying into the kitchen. The goblets overturned and the tablecloth caught fire. Thekla, Koebner, and Günther patted down the flames. Günther grabbed the water pitcher on the side table and doused the remaining flames with it. Sofia, Clio, and Mama Irene could be heard screaming in the kitchen. An iron pot fell to the ground and resounded on the stone floor.

When black bird flew from the dining room into the kitchen, Sofia dropped the pot she was scouring. Mama Irene and Clio screamed and hugged each other in terror. The bird flew into the oven and up the flue. The chimney stones buckled and cracked in two places. Black smoke poured from the fissures.

Sofia sprinted from the kitchen. “Uncle Spiro!” she exclaimed. “A black bird with legs and hands like a little woman flew into the oven and up the chimney!”

Uncle Spiro turned to Thekla: “Don’t translate that nonsense!” Thekla looked at Sofia. The woman showed no marks of deception. Thekla crossed herself in the Orthodox fashion.

“What’s going on outside?” Koebner said.

There was a noise. Everyone heard it. It was the sound of hundreds of rustling wings. Uncle Spiro went to the front door and opened it. In the light rain, he saw thirteen flocks of doves circling overhead. Then they merged into a single mass and flew off in the direction of the mountain pass. Uncle Spiro slammed the door. This was the witch’s doing, goddamnit! He had to calm his guests.

“Just the wind!” he said with a grin. “It’s late. I think we should turn in. Don’t worry about the mess. The women will clean it up.”

Philippa of the Holy Vision stood at the window on the second floor of the carpenter’s house, directly across from Uncle Spiro’s mansion. Her bloody eyes peered from behind the veil covering her face. She saw the witch’s doves heading toward the mountain pass. But the black dove, the leader, Queen Hecate, flew into Philippa’s weaving room.

Philippa closed the jalousies and turned around. The ghost of her mother, Yiayia Elena, stood over the Turkish brazier, which now began to glow. The ghost of Elena wore the Albanian headscarf with the coins sewn into its edges. She looked young and beautiful. In her right hand, Elena held a distaff, and with her left hand she beckoned Philippa to approach.

The room was cold and loud with the buzzing of mosquitoes. The insects were feeding on the puss oozing from Philippa’s pupils. Philippa went to her mother and, with her thumb and forefinger, drew a single strand from the distaff Elena held. The thread was slimy. It was the gut of a rat. When Philippa had drawn the cord to its just length, the spirit body of the witch in the mountain pass stepped into the brazier’s light, seized the cord with both hands and bit it in two with her rotting teeth. Then the three figures shook in silent mirth.

That night Thekla had a dream similar to the one she’d had on the flight from Milan to Ioannina. She walked over the rubble and shattered columns of an ancient temple. The sky overhead was leaden. She entered a precinct covered with a mosaic depicting the three Fates. An oak tree rose in the midst of the temple, its roots bursting out of the mosaic’s tesserae. One of the tree’s limbs was hung with bronze fragments that clinked in the wind. The same sound could be heard even when the fragments didn’t stir.

Egon Koebner and Günther Rippenberg stood close to the tree. Three women in black robes were standing between the men. The women’s faces were concealed in the shadows of their hoods. An oily gray cord extended from the navel of each man. The cord was connected to a distaff that one of the women held. Then Thekla looked down at her own navel and saw a third cord extending from it to the distaff. But the three cords looped together into a knot, like a glob of phlegm, which hovered in front of the shrouded figures.

Then each woman pronounced a curse.

“May the young man’s lust destroy him, so that he loses his head and goes mad, mad, mad.” The woman spat her curse on the knot.

“May the picture maker lose his vision, but see horrors that drive him mad, mad, mad.” The second woman spat her curse on the knot.

“May the bitch that shares our blood feel the pricks sting until she’s goaded mad, mad, mad.” And the third woman spat her curse on the knot.

The grinning face of the witch in the mountain pass emerged from the folds of her hood. She drew a pair of rusty shears from her robe and snipped the cord coming out of Günther’s navel. The young man opened his mouth and emitted a silent scream, as his eyes expanded in horror and he turned to stone. Then his neck cracked and the head fell to the mosaic floor. The witch sliced the film director’s cord, and the Koebner instantly tore out his eyeballs, laughing. Then he crammed the bloody vitreous pulp into his mouth, and chewed the mess with gusto, baring his gory teeth like a child at the supper table. His optic nerves clung like damp strings to his cheeks.

“No,” Thekla said, as the three women glided toward her. The witch held the shears high in the air. The knot of phlegm floated up into the thickening clouds, or perhaps into the thickening flocks of the doves; for both were simultaneously in the sky, even though (impossibly) neither of them was. The hood of one of the three had fallen back. She wore an Albanian headscarf with coins woven into its edges. The third woman was the veiled lady she had seen praying in the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God.

Thekla tried to run, but her feet were rooted to the ground; rooted to the roots of the oak tree. The veiled woman began to shriek and wipe her arms, from the elbows down, as if her arms were unclean. She wiped her arms more and more frantically, until she was wiping her arms more swiftly than was humanly possible.

Thekla woke up, gasping. She was in her bedroom on the upper floor of Uncle Spiro’s mansion. She suppressed a scream. The mosquitoes were stinging her. It was pitch black in the room. She slapped at her arms, which were sticky. But now that she was awake, she no longer heard the insects. They were no longer there.

Thekla went to the pitcher and basin of water on the chest of drawers. She pushed open the window so she could see. It was just before dawn. Overcast, but no longer raining. The scant light fell on her arms, which were black with blood. She washed it away as best she could and felt the red bumps where she’d been bitten.

The Albanian men on the raft could be heard in the distance reciting the dawn prayer in Arabic. Thekla looked across the way at the carpenter’s house with its second story projecting over its ground floor. A single window on the second floor was open. The veiled woman stood at the window, staring at her. Thekla closed the shutters and covered her face with her hands.

The Albanian men finished their prayers, and rolled up their rugs.

“Abu Shahed!” One of the men whispered urgently.

Kareem stood up. “What?” he asked.

The man was pointing in the direction of the hill leading up to the mountain pass. Three black-robed women were walking in single file up the hill. They turned their steps in the direction of the church. They continued to climb upwards in the misty air, even though there were no physical steps for them to mount.

Kareem remained silent. But his two comrades started to shake and cry out: “Allahu Akbar! Allahu Akbar!”

The shrouded women continued their ascent until they stood in a circle over the dome of the church. They held their hands together and formed a circle. Then a peel of thunder and hideous laughter rippled through the damp morning air, as the women condensed into gray balls that flew off like shooting stars in three different directions: one darted to the carpenter’s house, one fell aslant into the graveyard behind the church, and the last rose high in the air and plummeted straight down into the depths of the mountain.

At this, the youngest of the crew fainted away. The other man grabbed Kareem Abu Shahed around the waist and began shaking and groaning.

Kareem recited the Surah of Daybreak from the Holy Qur’an, which was used as an apotropaic against witchcraft:

In the Name of God, the Compassionate and Merciful. Say: I seek refuge in the Lord of the Daybreak from the evil that He created, from the evil of the louring darkness and from the evil of women who spit curses onto knots.

The pale light of dawn pierced the mists of the eastern horizon and scattered the shadows along the foothills of the black mountain over Dagitsidos.

Oh my, some truly disturbing imagery in this one! I like the way you tie all of these scenes together--the priest's sermon, the knot in the dream, the verse from the Quran. Nicely done.

The opening scene made me think of the book by Daniel Ogden on Greek and Roman necromancy. Have you read it? It's full of wonderful Witch of Endor type stuff, without all the smiting afterward ;-)

Also, not sure, but: "However, you’re welcome [to] camp"?