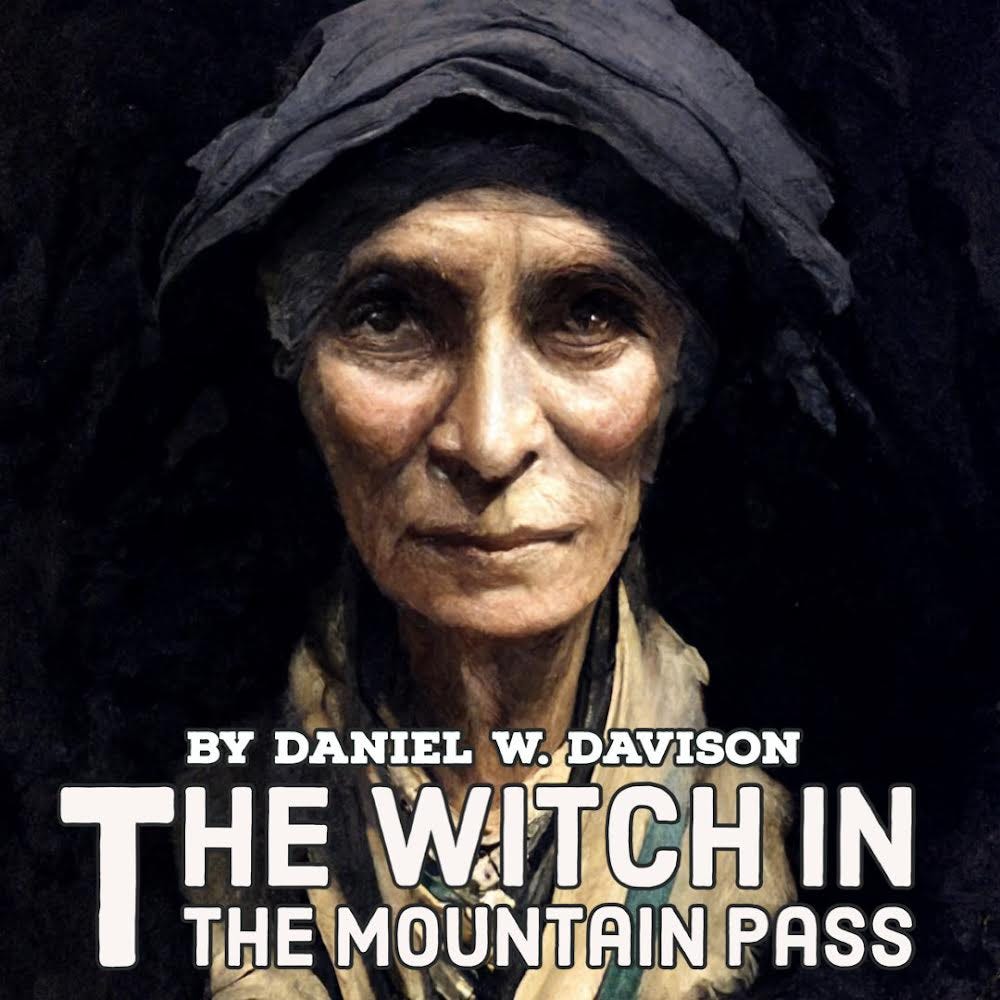

The Witch in the Mountain Pass: Chapter 7

A Novel

Evil seems good in the eyes of those whom Zeus guides to their end. (Soph. Antigone 630-633)

Chapter 7: Customs and Manners of the Greeks

Hoisted up by its hind legs, the boar’s screams of terror sounded almost human. The ropes slid over the greased crossbeam. The loopings around its hind legs cinched until the legs cracked under the torsion. Uncle Costa wore a leather apron. The four adolescent boys helping him were clad in nothing but burlap loincloths. Their clothes had been left in the swineherd’s hut because once the cutting started they’d be drenched in blood. After the slaughter, the boys would run laughing to the river Acheron where they’d bathe and wrestle in the cold September water. Then, emerging from the river of death, they’d tell one another that this was life; and the blood-soaked loincloths would be burned.

“The killing yard”—as Uncle Costa called it—was slick and oozy with black mud. The carpenter Loukos had brought planks and boards in a donkey cart to set down a makeshift path for the German filmmaker, Egon Koebner. The director wore tan spats and a swastika pinned to his lapel. He stood on an upside-down crate sunk in the mud peering through the rolling camera’s lens. A maze of duckboards criss-crossed the yard.

The young diplomat, Günther Rippenberg, was again tasked with managing the cables and equipment. He kept an eye on the portable battery to keep it dry. The lower half of the battery was lodged inside a wooden case that provided it with some protection. Günther had also set up an audio recorder in front of the camera, and its horizontal reels were rolling. Koebner wanted the boar’s screams on tape so he could dub it into the film. He claimed that if this was done correctly, the sound would not only unsettle viewers but would become associated in viewers’ minds with the Greek peasantry and enhance their revulsion toward them. He based this claim on an article he’d read in an industry journal authored by a Viennese psychologist.

The carpenter’s son, Manolios, had refused to have anything more to do with the Nazis after they had shamed and insulted him in front of his wife and townsfolk the previous day. The Nazis’ host, Uncle Spiro, in an effort to mend bridges, had approached Manolios’s father, Loukos, and asked him to provide assistance to the Germans, promising to waive the outstanding debt Loukos owed him for the land Manolios and Dorcas had decided to build their house on—an issue that had first come up at the wedding.

“No one has ever claimed that land.” Loukos told Uncle Spiro when the miser approached him about it at the reception.

“I know!” Uncle Spiro said testily. “Which means the land is mine!”

In bewilderment, Loukos had appealed to Papa Nikolaos for assistance. But the priest sided with Uncle Spiro because the town’s charter clearly stated that all unclaimed land in Dagitsidos (“save the land immediately contiguous to the property appertaining to the Church of the Dormition of the Mother of God”) belonged to the House of Andhroutsos.—“And I am the head of the House of Andhroutsos,” Uncle Spiro added as he applauded the cake cutting.

And so this morning Loukos arrived at the farm before dawn and set to work building the path and platforms. Everything was ready by the time the crew arrived. Loukos remained in front of the house by his donkey and cart, smoking a cigarette. But Günther came to him and saluted him. The young German could speak a few words of Greek, enough to get his point across. He asked if Loukos could help them. He wanted Loukos to hold a wand with a perforated bulb at the end of it, explaining through broad hand gestures that the wand would catch the sounds. The wand was connected to a box in front of the camera. The box had two spinning discs on it that looked like narrow wagon wheels. Loukos shrugged and agreed to do as Günther bid.

The pigpen was located on the other side of a low stone wall on the western end of the yard. Thekla Witte was standing on the wall to keep her clothes free of mud. She also wanted to be well enough away from the jets of blood when the pig’s arteries were severed. She wore a white blouse with long sleeves to hide the mosquito bites from the previous night. In lieu of slacks, she wore loose-fitting high-waisted gauchos called Hosenröcke (pant-skirts) in German. A pair of dark sunglasses had replaced her regular steel-rimmed glasses. The steel-rimmed glasses were frankly an affectation; she wore glasses because men took her seriously and treated her more respectfully when she had them on. It was overcast this morning, so she didn’t even need the sunglasses; but she wanted her eyes concealed when the butchery started.

As the boar screamed and kicked its forelegs, Uncle Costa spoke loudly to Thekla, explaining the reason he had erected a permanent wooden wall as a screen between where he stood and the pigpen. It was so the pigs in the sty couldn’t see one of their own hanging in the air. Otherwise they would sense what was happening and it could tinge the taste of their meat when it was time for them to be killed.

Thekla translated this to Koebner, and then looked over her shoulder at the pigs on the other side of the wall. The animals were pressed together as far as they could get from the boar’s screams. Some were shaking. Their eyes were wide with panic. Thekla turned around again. Two of the boys had placed hooks into the boar’s mouth and were pulling these back so that the animal’s head yanked up as if intentionally for the camera’s benefit. The gums bled. Thekla believed she saw a tear roll down the animal’s cheek.

Uncle Costa continued to speak: “If you strangle a pig or knock it on the head with a mallet before cutting into it, the blood is no longer quick and the Devil can slip out of its veins and crawl into you, like when Jesus drove the Evil One from the madman and cast him into the Gadarene swine.”

Thekla turned to Koebner as she translated because she had seen the serrated knife being raised.

Uncle Costa told the boy closest to him to step behind his shoulder. The boy did as he was told and dexterously maneuvered the hook handle out of the swineherd’s way. Uncle Costa cut into the throat. Blood spurted all over his chin and leather apron, gushing into the wooden vats the other two boys manipulated on the ground to catch the spillage. The tallest boy put down his hook and seized a cloth from a peg on the wall so he could wipe the feces welling from the pig’s anus to keep as much of it as possible from dribbling into the blood-vats for the black sausage.

Koebner switched off the camera and looked incredulously at Thekla. The primitivism of this child race repelled him. True, there were slaughterhouses in Germany, but the animals were killed humanely—with mallets—and the carcasses were processed in an assembly line fashion based on the principles and techniques perfected by the American genius Henry Ford. German butchers were not this barbaric, this messy, this grotesque. He blinked at Thekla who regarded him enigmatically behind the tinted glasses.

A few minutes later there was a loud crunch followed by the sound of flesh tearing. The boar’s head had been separated from its spine and thrown into the mud. Uncle Costa set about butchering the carcass. Loukos turned to Günther. The young man had switched off the audio recorder. He nodded to Loukos to signal that the carpenter no longer needed to hold up the microphone.

Günther put the audio recorder in its case. Then he stepped down into the mud and crouched in front of the pig’s head. Its tongue was hanging out. Günther curled his lips until his teeth were bared. He stared into the pig’s eyes. He wondered how long a severed head continued to be aware of what was going on around it. He remembered reading somewhere that, during the French Revolution, a physician condemned to the guillotine had instructed his apprentice to lift his head from the basket and take notes on how long he could alternately wink each eye. Evidently the physician’s eyes didn’t wink at all, as he had intended. The lips simply twitched and the roving eyes kept glancing in horror in the direction of his apprentice as if the dying brain still recognized him. Günther pushed the pig’s snout in with his canvas-gloved index finger. He snorted twice and grinned. The pig’s eyes were motionless, so there was no life left in this creature’s head.

“Günther!” Koebner shouted.

The young man rose and went to the director.

“It’s getting overcast again,” Koebner said. “Pack up the camera and the rest of the equipment and take it all back to the mansion. I’m done filming for the day.”

Thekla looked up into the sky. There were only a few clouds left and the weather was already clearing up. She sensed something else troubling the director. She walked the length of the wall toward the swineherd’s house.

When they were back at Uncle Spiro’s mansion, Thekla washed her face in the water basin in her room. She opened the window and looked out at the carpenter’s house across the way. The window where she’d seen the veiled woman this morning was shuttered. Thekla folded her arms and paced around the room. She suspected Koebner was scheming to get back to Germany as soon as he could. It was obvious he hated it here. She herself had mixed feelings about the place. She’d never been to a Mediterranean country and the quaintness of the town’s setting was pleasing to her. Last night’s dinner was undeniably dramatic. But a startled bird flying upsetting a dinner table wasn’t sufficient grounds for packing up and leaving. At least she didn’t think it was. But her own views held no water on this mission. And the few suggestions she’d made were brushed aside or sniffed at by the director and Günther both.

Thekla was worried that if Koebner left Dagitsidos on Monday, she would have nothing to show for this trip. What was it Reichminister Goebbels said to her? She would be able to conduct field research in northern Greece. He’d thrown that out as an aside—even as he held over her the threat of immediate dismissal from the university if she refused to accompany Koebner on the trip. All she’d done since coming to Greece was act as the director’s interpreter. Now that Koebner was considering cutting the trip short, her future prospects were once more in doubt.

“I’m not going to stay inside for the rest of the day,” she said to herself. She could hear the women singing in the groves behind the mansion. In her luggage was a small leather back containing a notebook and scientific equipment. On the chest of drawers was her personal camera, a boxy affair with an accordion-like lens. She put her steel-rimmed glasses on and smirked. Then she wrapped a red scarf around her head.

“What she doesn’t realize,” the witch in the mountain pass said, “is that we have given her a chance to avert her fate. We have shown her a possible future, not a fixed one.”

Philippa of the Holy Vision and Yiayia Elena stood with the witch in a twilight valley floored with asphodels. The flowers also blossomed from the edges of their robes.

“And yet,” Philippa interjected, “she is about to squander that chance.”

The three nodded and sighed, as they effervesced into the thickening mist.

Thekla had an idea. Günther had used that audio recording device this morning. Since the device belonged to the Reich Ministry of Foreign Affairs and was technically under his control, maybe he would accompany her and record the women’s work song. How can I entice him? she thought. I know, I’ll tell him that the little girl, Clio, might be in the fields too.

The moment this thought rose in Thekla’s mind, the skull of Yiayia Elena rolled to the side under its death shroud; and Philippa of the Holy Vision looked up from her loom and whispered, “Out of the heart proceed evil thoughts.”

The witch in the mountain pass rose from the table under the pergola of her taverna. She had been sitting with a Montenegrin family who were enjoying a lunch of grilled river fish that Dorcas had prepared for them. Clio was holding Dorcas’s baby, Tobias.

“What’s wrong with her?” Clio asked, inclining her head toward the witch.

Dorcas shrugged and scraped the grill to clean it.

Yesterday, after Papa Nikolaos’s fire and brimstone sermon against witchcraft, several members of the congregation were flummoxed. They stayed behind and asked him if they should stop talking to the witch and force her to shut down the taverna.

“Of course not!” he replied. “If you do that, the tourists will stop coming and the town will go back to being irrelevant.”

Perplexed but relieved, the citizens went back to treating the witch as their neighbor. As the boar was being slaughtered that morning, the baker set up his stand opposite the steps down to the Church of the Dormition. Dorcas’s father had unlocked his shoe hut in the canyon leading to the witch’s enclosure, but the tourist season was over and business was scarce.

Thekla knocked on Günther’s door.

“Komm!” he said. He had recognized her footsteps on the wood floor.

Thekla opened the door. Günther was sitting up on the bed, reading an old edition of Der Angriff.

The witch leaned against one of the poles sustaining the pergola. The little Montenegrin boy stopped eating and studied her, curiously. Something had startled the doves and they took flight from the ledges. The birds circled the enclosure and then flew into the cave leading down to the river Acheron.

Thekla breathed in deeply and said, “I want to do some research in the fields and I was wondering if you would be interested in joining me. I would like to have a recording of the women’s work song.”

Günther grinned but refused to look up from the magazine.

She continued: “Herr Koebner would be able to use the recording as well… for his film.”

The young man threw the magazine aside and stretched. Then he rose from the bed. “Why not?” he said.

Thekla was relieved. His own ambition had determined his course. She didn’t even have to mention the girl.

“Too late!” the witch said and spat in the air. “Too late,” she repeated. Then she hissed and mumbled an ancient spell.

“Who is that lady talking to?” the Montenegrin boy asked his mother.

“Someone who has no future,” the woman replied, picking meat from the fishbone.

Thekla left Günther’s room and walked back toward her own, scratching her forearms. The mosquito bites had all flared up at once.

Now that lunch was over, Dorcas removed her clogs so that her feet could breathe again. She only wore shoes while cooking as a precaution against the falling coals and ash. She had cleaned and scoured the grill. She reached down and took Tobias from Clio. There would be no more guests today.

Clio kissed the baby on the brow before handing him to her.

“What’s wrong?” Dorcas asked.

“I wish I was lucky like you. I want to have a baby and a husband one day.”

Dorcas smiled down at the girl. “You’ll be lucky like me one day. You know, there’s a secret to luck… The witch told me.”

“What do you mean?” Clio asked.

“Luck favors those who are grateful for it. When something good happens to you, say ‘Thank you.’ After that, more luck will follow.”

Clio turned away and regarded the witch who was now looking directly at her. She seemed not to notice the girl. The black dove, Queen Hecate, flew down from the high ledge and landed on the witch’s shoulder.

Thekla and Günther were stood in the olive grove near one of the stone walls that seemed to be as common to Dagitsidos as stray cats in Berlin. Günther was setting up the audio recorder. He had brought a smaller battery than the one he’d used at the pig farm.

Several children had gathered around Thekla to look at the camera and scientific instruments.

“Who wants to be first?” she asked the children.

“Me!” a boy said. He sat on the low wall.

The other children stood around giggling.

Thekla removed the calipers and told the boy to hold still. She measured the width of his head and recorded this in her notebook. Then she removed a ruler and told him to keep his mouth closed and look straight ahead. The boy pulled a funny face and the other children laughed.

Thekla grinned and addressed him Greek slang: “Simmer down, you little turd!”

The children burst into laughter and the boy giggle and said, “She says ‘simmer down, you little turd’ like Mama Irene!”

“What?!” Mama Irene said from a nearby tree.

Thekla stood up straight. She grinned and wagged her finger at the boy. Then she grabbed her camera and turned to look at Mama Irene who was standing with a basket full of olives.

Suddenly, Thekla froze. Standing in the treeline behind Mama Irene was the veiled lady. No one seemed to notice her—not even Günther, who had turned on the recording machine and was holding the microphone toward the women. The laborers resumed their work and began singing their work song:

We are the dames of Dagitsidos. From dawn till dusk we’re on our toes. Our men are stumps as God well knows. They smoke and fart, playing dominoes.

They repeated the same four-lines and at the end of each iteration, one of the women would shout, “Oopah!”

The veiled woman started to wipe her arms as if she was cleaning them. Then one of the girls screamed and pointed at Thekla because spots of blood were appearing on her white sleeves. The stains were growing. Thekla dropped her camera and started scratching her arms because the bites suddenly itched tremendously. She looked up in a panic. The veiled lady was gone and the women were running toward her, asking her if she was alright. She was sweating. Günther looked at her in horror and lowered the microphone. Thekla fell to the ground in a swoon.

When she woke, she was back at Uncle Spiro’s mansion in her bed. The miser stood at the threshold wringing his hands. Old Agatha, who was known throughout Epirus for concocting effective medicinal balms, had been summoned and was applying a white poultice to the bites on Thekla’s arms.

“Nasty,” she commented out of the corner of her mouth while smoking her clay pipe. Egon Koebner emerged from his suite. The director looked haggard.

“What’s going on?” he asked. Neither Uncle Spiro nor Agatha could understand what he was saying.

“Where’s Günther?”

Uncle Spiro recognized Günther’s name and recalled that the young man had left the mansion. Uncle Spiro pointed vaguely in the direction of the front of the mansion and said “out!” in English.

“I have as much right to be in here as you!” Koebner snapped in German.

Thekla spoke from the bed: “Herr Direktor, our host is saying that Günther went outside. I think he’s gone to see if he can find a way for us to leave as soon as we can.”

Koebner looked at Thekla’s bare arms smeared with the poultice. Then he squinted and turned away, covering his eyes.

Agatha, worried that her pipe smoke was what had irritated the German’s eyesight, made a halfhearted effort to wave the smoke away.

“Are you okay, Herr Direktor?” Thekla asked.

“I just want to be done with this place,” he said and walked out of the room.

Although he didn’t know German, Uncle Spiro intuited that the director wanted to go home. Spiro was concerned that if the Germans left Dagitsidos with a bitter taste in their mouths, it could jeopardize his plans to solicit their assistance in securing a contract with the Reich as a supplier and middleman for the Istanbul-Baghdad railway venture. This can’t have come at a worse time, he thought. Tomorrow was the Sabbath and the day after that would be the Lord’s day. No one in town would be permitted to work on either of those days, and it was too late now to send for the mechanic in Glyki to prepare his truck to drive them out of town on Monday.

Uncle Spiro left Thekla and Agatha, and went down the broad staircase. He paused at the half-landing and studied the oval portrait of his ancestor, Odysseus Andhroutsos. Then it came to him: Kareem Abu Shahed and his crew! The Albanians would be able to work both tomorrow and Sunday. He could hire them to get the Germans to Glyki and then to Parga, where his cousin, who had a yacht, would be to get them to Trieste or Venice.

The director was saying something to Spiro from the top of the steps.

“What?” Uncle Spiro said in English.

“I said that I’m not leaving until I film the witch in the mountain pass.” Then Koebner blinked and held one hand in front of his eyes.

“Ah… i Mágissa?” Uncle Spiro asked.

“Die Hexe (the witch)!” Koebner repeated in German.

Uncle Spiro nodded and smiled broadly. “Yes,” he said in English. “Witch!”

Günther walked up the slope toward the entrance to the mountain pass. It was late afternoon and the sky had again become overcast. A mist was rising up from the river.

This trip is turning into a fucking disaster, Günther thought. I’ve got to find a way to wire the embassy in Athens or contact Berlin.

Günther passed the baker who was waddling down the hill in his direction. He held an empty tray. Not a single customer had patronized him all day, so he’d closed up his stand and eaten the remaining inventory.

As the baker passed Günther, he smiled and hooked his thumb in the direction of the mountain pass, saying in English, “Moon Day!”—by which he meant to imply that on ‘Monday’ he would reopen his stand.

Günther looked up. Weirdly, a full moon could be seen peeping through the gray clouds of the late afternoon sky.

“Moon Day,” the witch whispered to Queen Hecate who cooed in the old woman’s cupped hands.

Something had caught Günther’s attention. He looked down at the courtyard of the Church of the Dormition. Someone had entered the cemetery. The young man smiled.

Clio descended the steps of the terraced cemetery. Her mother, Mama Irene, had said to her: “Leave this small bag of almonds at Papa Nikolaos’s residence; and then leave this second bag on the grave of Yiayia Elena.”

Midway down the steps, the girl went to the stone sarcophagus that stood above the weedy soil marking the final resting place of Philippa’s mother. A flat unadorned slab covered the grave. Clio placed the small bag on top of it. She noticed that the side of the sarcophagus was cracked. There were asphodels growing under the crack. She bent down and smelled the flowers, but the scent was overwhelmed by an even sweeter odor issuing from the cracked sarcophagus. It smelled of sanctity. Like jasmine, Clio thought.

Then she stood up and gasped. The blond man was standing at the top of the cemetery steps. He was looking down at her. “Éla, korítsi (Come, girl),” he said quietly in Greek.

Clio was afraid to scream. Papa Nikolaos would doubtless hear her and think she was mad. She didn’t know why the strange German was talking to her and grinning that way. She looked behind her. The crumbling steps led down to the Acheron. She turned and ran.

She had to watch her step so that she didn’t trip. She heard the man walking unhurriedly behind her. Why was he following her? At the base of the steps she turned around. He too stopped. But only for a moment. “Éla, korítsi,” he repeated.

Clio stepped into the cold water. Her feet touched the sunken walkway. The water rose to her chest as she struggled to wade toward the cave chapel where the corpses of the dead had been washed in former times. She heard the man step into the river behind her: “Éla, korítsi.”

He was moving faster. To her horror, she felt him touch her hair. She screamed.

The water was up to her neck by the time she reached the ledge of the chapel. She pulled herself up and turned around. The man was directly underneath the ledge of the cave chapel. She ran to the rear of the chapel and paused at the mouth of the tunnel leading up to the enclosure where the witch lived. The man lifted himself out of the water and stood frowning at her.

Clio turned and ran. Günther looked at the ancient frescoes on the wall. The shrouded figures seemed to be pointing down at him. The eyes of the figures had been scratched out. When he had entered the river, he removed the penlight from his breast pocket. Now he turned it on and entered the tunnel.

The witch in the mountain pass heard Clio scream. Hecate was cooing even more calmly. The witch leaned into the black dove as if to kiss her. But then suddenly she bit the bird’s head off and spat it to the side. Blood drizzled down the witch’s chin as she threw the feathered carcass into the air. But the wings outspread and the head of Hecate emerged from its spine as she soared unscathed up toward the clouds and the full moon.

Clio couldn’t see anything. She was worried that she would trip in the pitch-black tunnel.

With the penlight, Günther moved with ease and Clio could sense that he was gaining on her. She had to get away from him. She knew he was trying to harm her in some way, although she could not fathom how or why. She could see far up the slope the dimness of the enclosure. Standing at the cave’s entrance was the witch.

She had almost made it to the witch when she cried out in alarm because the man had thrown a boulder at her. The missile flew over her shoulder and landed in front of her; but it didn’t sound like a rock when it struck the ground.

Clio saw the old woman’s face streaked with blood. The witch was grinning. Clio turned around and, from the faint moonlight streaming in from the enclosure, she saw a headless torso collapse in the tunnel. She gasped and looked down at the boulder the man had thrown at her. It wasn’t a boulder. It was his head.

The girl fainted. But before her body hit the ground, the ghost of Yiayia Elena scooped her up and bore her over the twitching corpse of the dead Nazi. Down through the mountain tunnel, the ghost of Elena bore young Clio—down to the ancient funereal cave chapel and over the black waters of the river of death.

The witch in the mountain crouched down until her spine cracked and her face swiveled in an unnaturally parallel arc until it faced the severed head. Günther’s eyes were wide with horror but fully aware of what was happening.

“How long does a severed head remain aware of its surroundings?” the witch asked. Then she snorted like a pig and pressed her finger against the German’s nose. “In your case,” she said, “forever!”

Then she pulled back the hood of her robe, and the hairs on her head rose up and writhed and turned into snakes. The witch bared her rotting teeth in a hideous rictus and the severed head and bleeding torso of Günther Rippenberg turned into stone.

Clio felt a hand touch her hair. She woke up, gasping. She had somehow fallen asleep next to the grave of Yiayia Elena. It was night and the moon shone full. As her eyes adjusted to the dark, she thought she saw a woman’s hand retracting into the crack in the side of the sarcophagus. Clio remembered kneeling down to look at the asphodels. She remembered the fragrance issuing from the grave. But that’s all she could recall.

She needed to get back home. Mama Irene would be worried sick. Clio stood up and grabbed the little bag of almonds that lay on the top of the grave. She pushed the bag into the crack in the side of the grave. Then she ran up the cemetery steps. Suddenly—and she knew not why—she felt an overwhelming sense of gratitude well up inside of her. The girl stopped at the cemetery and turned around one last time.

“Thank you, Yiayia Elena,” Clio said, smiling. And the skull in the jasmine-scented tomb smiled, too, beneath its rotting burial shroud.

Agree with Adrian! Really enjoyed the visuals with this (though relieved there were no pigs :-( ...) And I like how your chapters often complete a circle thematically, in this case with the severed heads, etc. Nicely done!

Great work with the Midjourney integration, Daniel. I can only imagine the key words!