I published the first part of this story on Substack earlier this year. Someone suggested I submit it to a literary magazine. To do that I had to un-publish it on the platform. I submitted it and immediately received a rejection stating that their magazine did not publish “fantasy” tales. So I’ve updated it and reposted it here.

The Invisible Library of Kafr Musa: Part 1

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

My friendship with Professor Sami al-Ghali began in 1954 during his residency at the Institute of Oriental Studies in Moscow. He came to the USSR as part of an academic exchange sponsored jointly by the governments of Premier Georgy Malenkov and former Egyptian President, Maj. Gen. Mohamed Naguib.

Professor al-Ghali (whom I shall refer to here as Sami) was a Coptic Christian, the scion of a prominent family of cotton exporters from Alexandria, Egypt. He could not speak Russian but was fluent in German, French, and English, the latter of which he taught us Arabic in.

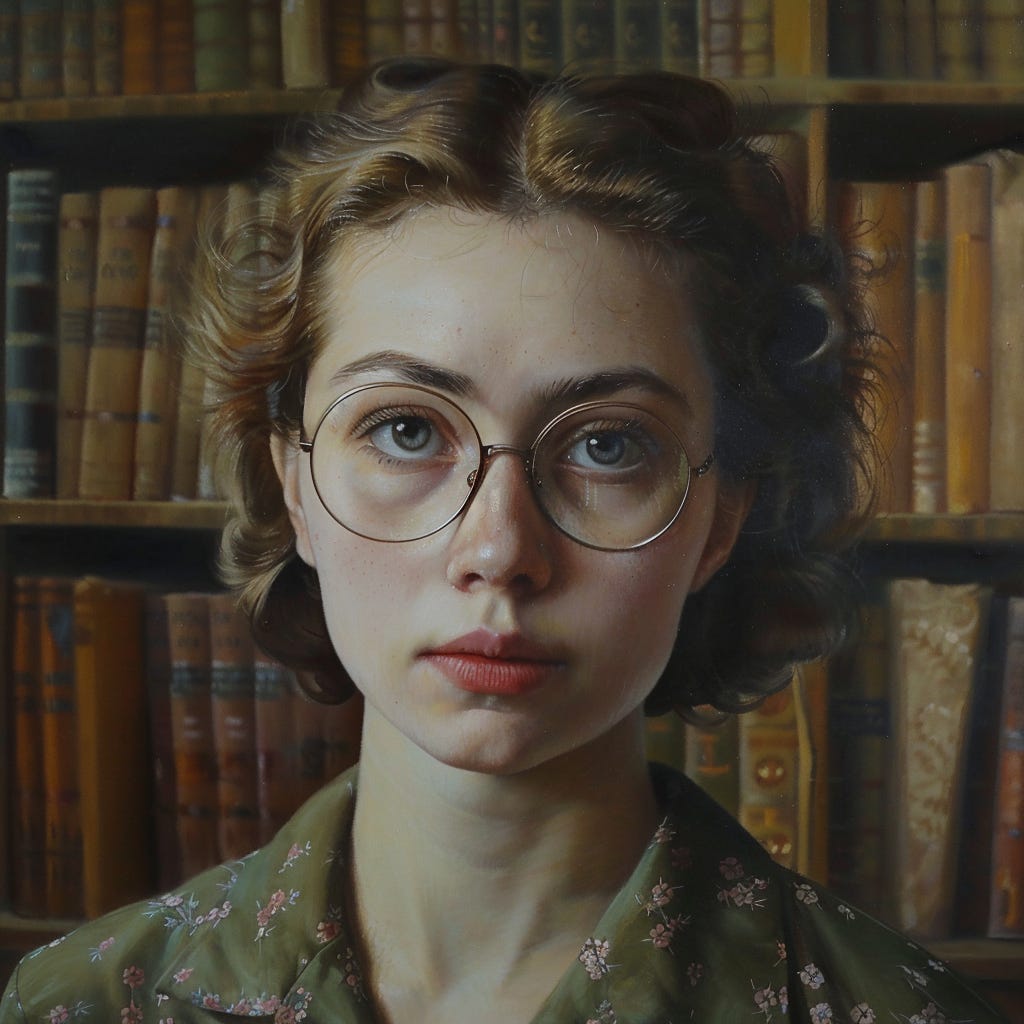

I was a young woman of twenty-four when we met. He neither made crude insinuations about my sex nor treated me as an inferior. He flattered me outside the classroom by continuing to speak to me in Arabic, gently pointing out mistakes I had made so that I could improve my fluency in the language, which was already deemed by the institute’s proctors to be rather advanced.

Sami was a handsome man in his mid-forties, but a crashing bore. He would ramble on about Graeco-Roman history or share his outré theories concerning the recent discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library in Upper Egypt. In class he would descant ad nauseum on the virtues of the Coptic language, a subject entirely irrelevant to our needs.

I once had the unenviable task of explaining to him that the reason that his guests had departed early from a soirée that he had hosted was not because they could not understand his English, but because they were bewildered by his discussion of Gnostic Archons, and could not have cared less that the Arabic word tamsah (crocodile) was of Coptic derivation.

He threw up his hands and laughed full-throatedly at my candor. “Where were you, habibti (my dear), when I was a lovelorn young man? We would have made a marvelous pair.”

How I wanted to tell him that we could still make a marvelous pair. But I did not dare cross that line. Besides, I did not have the words in English or Arabic to express my feelings to him without sounding like a simpering school girl, which, in retrospect, I was.

From an early age Sami had demonstrated an aptitude for languages but none for mathematics or trade. This was a source of consternation for his parents, Zakariya Bey and Leila Hanum, who had cherished the hope that, if their son was not cut out for the family business, then perhaps he would honor them by becoming a priest and marrying the daughter of Boutros Salim Pasha, a banker from Al Minya with ties to the King.

But Sami had confided to his parents that he was an agnostic.—“Whatever that means,” Leila Hanum would remark with tears in her eyes. The boy showed only an aloof and ironic interest in sacred matters, which the Coptic community of Alexandria regarded as an embarrassment verging on scandal. So in 1931 it was decided to send him abroad, since the only thing he would ever be fit for was the civil service.

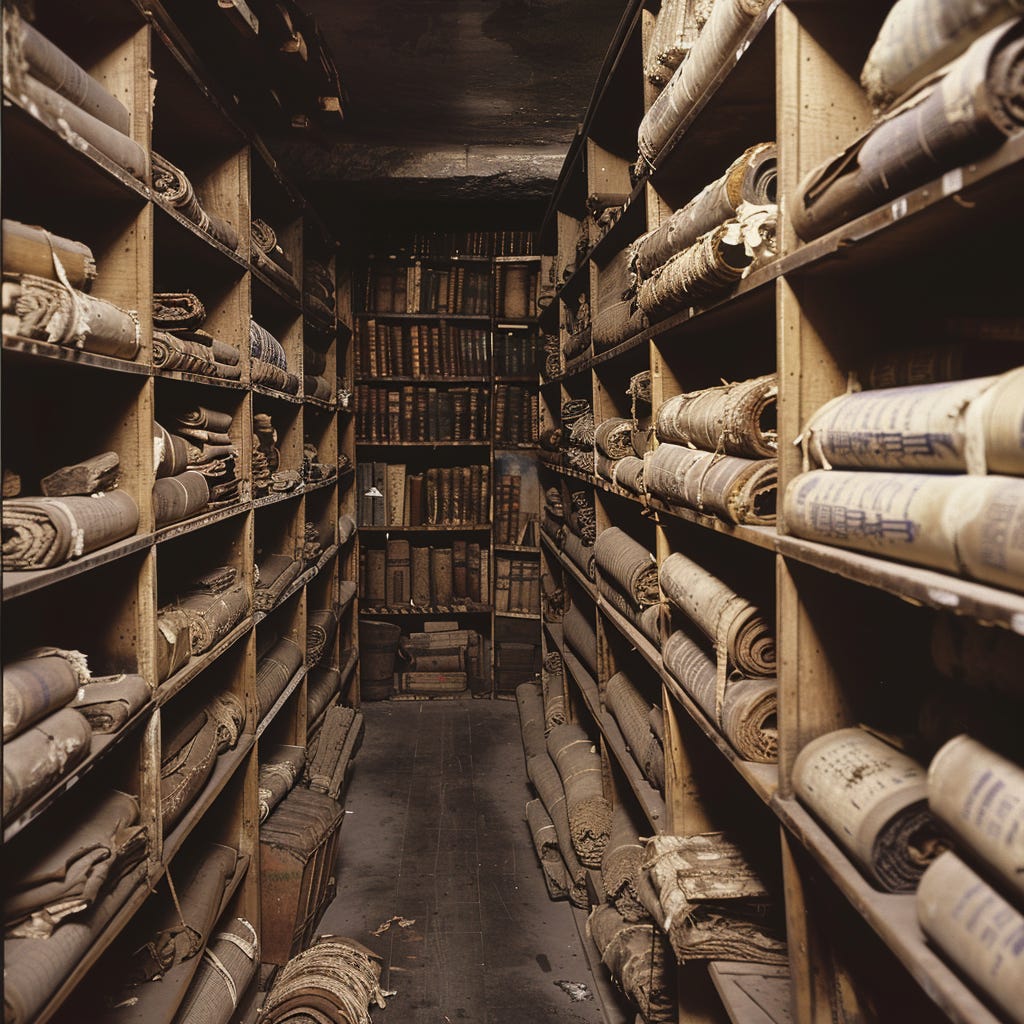

Sami attended Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin, doing yeoman’s work cataloging and translating a cache of Coptic manuscripts he had independently discovered in a neglected and musty annex across the street from the library. It housed an overflow of mouldering books from the university stacks, as well as a bewildering array of ancient Egyptian scrolls, codices, potsherds, and stelae.

But the eeriest section of the annex was a wide space between the bookshelves where seven wooden coffins were kept. The staff of the library avoided what they called der Schuppen (the shed), partially out of a Teutonic aversion for the cold drafts that crept in through the annex’s boarded-up windows, which were still perforated with bullet holes from the 1919 Spartacist uprising. But the main reason the annex was avoided was that it was believed to be haunted.

An elderly librarian had sworn that, one afternoon, as he carried a handful of books into the shed to deposit them there, he glimpsed a figure swathed in tea-colored shrouds behind one of the bookshelves. Then there was the story of the charwoman, who (at the height of the Great War) was found dead in one of the coffins—a tranquil smile on her face, as if she’d laid herself down to take a nap. (Actually, this last story was a complete fabrication but had been passed down among the students and faculty of the university for so long that it entered into the collective lore concerning der Schuppen.)

The relics in the annex were the fruits of an archaeological excavation carried out under the auspices of the renowned German Egyptologist, Herr Ludwig Borchardt, between 1912 and 1914 at a village in the Fayyum called Kafr Musa (the Hamlet of Moses), where local tradition holds the son of Amram was born. The village lies 10 kilometers west of the ancient city of Arsinoë, formerly Crocodilopolis.

Sami kept his discovery of this cache a secret, refusing to share it even with his close friend and fellow student, Pahor Labib, a man whom in later years he would regard as an intellectual rival.

I feel compelled to comment on Sami’s experience in Germany in the years leading up to the Second World War. He claimed to have been oblivious to the ominous winds blowing through Europe in the 1930s, though he admitted that both he and Pahor Bey had found it puzzling when, in late 1934, they had been obliged to resubmit their passports and letters of recommendation to the registrar of the university, so that the Reich Ministry of Science, Education and Culture could verify that the two Egyptians were neither Jews nor Romanians.

“But on the whole,” Sami remarked, “Germany seemed a rather civilized and peaceful place in those years, so long as a man kept his eyes to the ground—or his nose in one of the books that had not yet been burned.” He smiled vaguely as he told me this.

On returning to Cairo in 1937, Sami again had access to French and English newspapers, which had been suppressed in Germany during his time there. It was only then that he realized the world stood on the brink of a cataclysmic upheaval.

One afternoon, at Sami’s invitation, I went to his flat overlooking Moscow’s Palace Quay. The accommodations which the Soviet Ministry of Culture had provided him were far more opulent than the squalid blockhouse I lived in, an edifice that in later years we Muscovites would refer to as a Khrushchyovka.

Ushering me inside, Sami seized both my hands, whispering into my ear that he had a matter of the utmost urgency to communicate to me. He said that he would speak in English so that I could understand every word that he had to say.

My cheeks flushed in anticipation of a romantic overture. But to my disappointment, he indicated that he wished to share with me a discovery he had made, a discovery that would earn him a place in the annals of Egyptology alongside the names of Howard Carter and Jean-François Champollion.

I pushed up my glasses and, at his bidding, took a seat. He offered me a Turkish cigarette, which I greedily accepted.

“I came to the Soviet Union,” he began, “because I needed to occupy my days with something comparatively menial, like teaching brilliant young students such as yourself Arabic, so that I could devote my nights to formalizing a theory that I have been evolving over the last two decades. It is not my wish to seem vain, Yulia, but my labors have finally, as the English say, ‘paid off’.”

“Please explain, Gospodin Professor.”

He nodded, pacing the room as I savored the richness of the unadulterated tobacco and the comeliness of the professor’s profile.

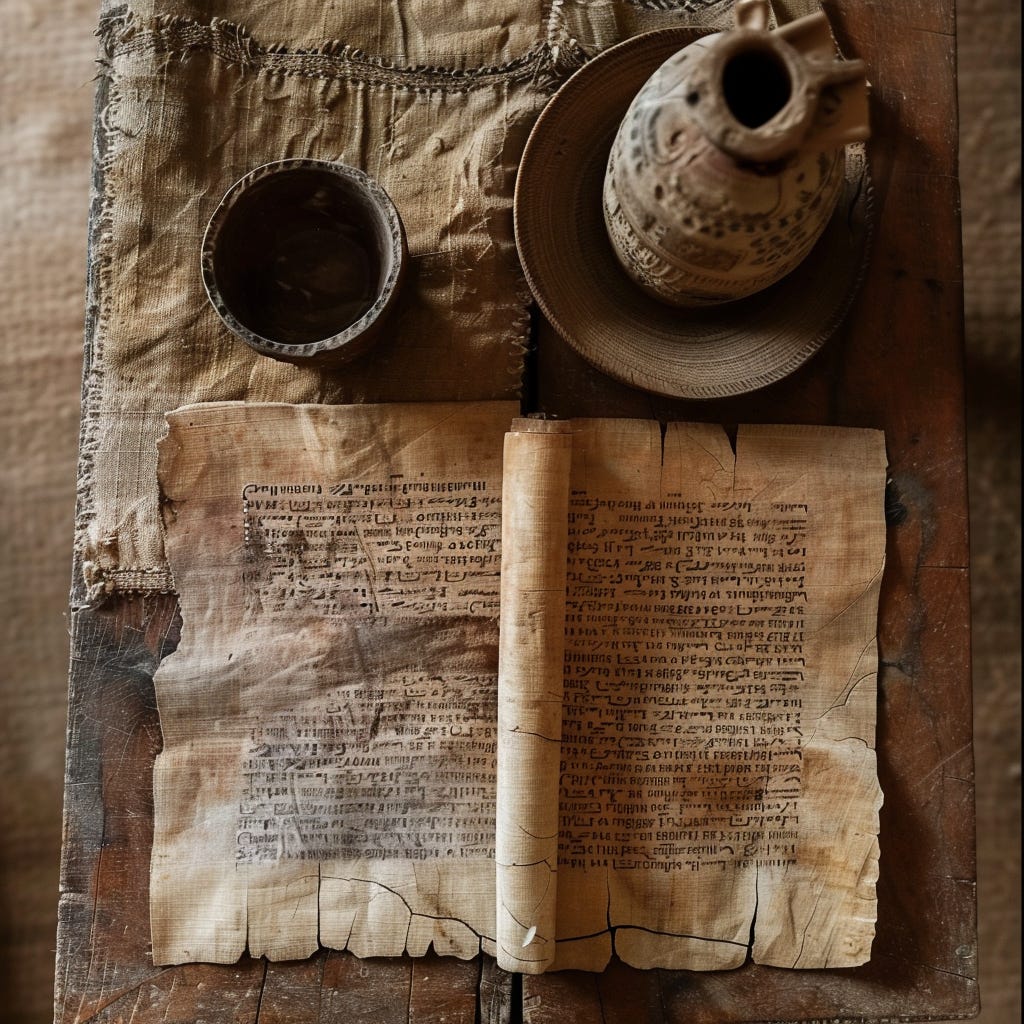

“I have spoken to you before of the excavation at Kafr Musa. The manuscripts discovered there are written entirely in Coptic. They are mostly spells, prayers, incantations. One of the codices was bound in cartonage that includes a fragment of a letter from a merchant in Caesarea who refers to ‘the recent Bar Kokhba uprising.’ This could indicate the tomb dates to as early as the mid to late second century of the Christian era, making it older even than the Nag Hammadi Library.”

He showed me a map of the site and a separate diagram of the excavation. The layout of the tomb was accompanied by arrows and lines, showing the dimensions of the compartments and shafts, along with a few annotations written in a crabbed hand, indicating the dates certain items had been found.

“In the central chamber, six coffins were arranged in a circle around a seventh. The head of each coffin was decorated with what is called an encaustic portrait, in which the pigments have been applied directly to a surface of hot wax and dammar gum. The paintings are beautiful. Strikingly realistic. The central coffin was the only one with the face of a woman. It was also the only one that contained no mummy.

“An inscription indicated that it belonged to Sophia, which, as you know, is the Greek word for wisdom. The interior lining of the coffin was covered in minuscule Coptic letters, forming words and sentences, such as the following: Sophia dwells in the realm of the great Invisible Spirit, which lies in the lacuna (gap) between the logoi (words).”

I exhaled a stream of smoke. “I don’t quite follow.”

Sami quoted from memory:

To find Sophia the postulant shall navigate the unseen realm of Domedon Doxomedon, a realm created by the Father of Silence and Premeditation. The portal is guarded by Eleleth, son of Sophia, Demiurge and Creator of this our sublunar world.

Once the veil has been lifted and the Seeker has entered the Pleroma, he shall gaze upon the majesty of Sophia enthroned, at which time the mirror image and sister of Sophia, Metanoia (Repentance), shall appear in the coffin, where she has been sleeping all along.

He went to a stack of papers and notebooks on the desk.

I lowered my eyes, dismayed. I have always considered religion and mythology to be the intellectual cesspits of human history. They cannot hold a candle to the social advances that have been achieved in the twentieth century through a rigorous and practical application of the principles enshrined in the writings of our own prophets of Communism and Dialectical Materialism.

Sami handed me an open notebook with a few Coptic letters that he had written out, apparently for my benefit. Although I cannot read Coptic, this was not germane to his argument.

“The coffin inscription closes with an invocation to Domedon Doxomedon: He who came from Silence and dwells in it, he who has an invisible name masked behind an empty symbol. . .

“Following that phrase, there appears a string of vowels, which I have separated here with a vertical line to highlight the point of repetition: IEOUEAO | IEOUEAO. In isolation, IEOUEAO could possibly be an abbreviation for Ieou is the Alpha and Omega.

“Ieou was believed by some Gnostics to be the true name of God. What is curious about this invocation is that, immediately after the string of letters there is a lacuna that has been intentionally gouged out of the coffin wood. And then, the same sequence of vowels has been palindromically reversed and mirrored on the other side of the lacuna, so that the inscription reads thus. . .”

IEOUEAOIEOUEAO [. . .] OAEUOEIOAEUOEI

“I would hardly call this groundbreaking, Gospodin Professor.”

“Please, habibti, stay awhile, that I may elaborate. . . At first, the discovery appeared, as you say, ‘hardly groundbreaking.’ So I turned my attention to a close examination of the manuscripts that were found in the tomb.

“Patterns began to emerge. There were odd interruptions within the texts. Clusters of Coptic letters, not always vowels, appeared mid sentence, followed by ribbons of unrelated narratives that sometimes lasted for several pages. After this, there would be another random sequence of letters.”

He beckoned me to the desk, taking up a pencil and scrap of paper.

“Allow me to demonstrate. Let us take the letters Lambda (L), Kappa (K), Delta (D), Alpha (A): LKDA. These letters might appear in the text as I have written them here. Then a phrase, such as ‘Look to the light’ would follow. After this, there would be a new series of letters.—Say, Delta (D), Omicron (O), 3 Betas (B), and Kappa (K): DOBBBK. It was obvious that I was confronted by a cypher of some sort.”

I nodded. “Perhaps a form of textual pointing. Or should I say, punctuation?”

“Precisely! Now, imagine my surprise, Yulia, when I located IEOUEAOIEOUEAO a second time in the middle of a scroll, a recipe for a magical theriac. This was the same sequence of letters that had appeared to the left of the lacuna in the coffin.”

I looked at him curiously.

“But this time IEOUEAOIEOUEAO was followed by the phrase, ‘Eleleth permits you to pass through the gate and begin your quest.’ It was then that I realized that these seemingly random groupings of letters, each of which had a sister somewhere in another manuscript within the archive, were the locks and keys, the hooks and hinges, binding together the books of an invisible library that had been figuratively compressed into the lacuna inside the coffin of Sophia. I had found the library’s opening sentence. . .”

IEOUEAOIEOUEAO | IEOUEAOIEOUEAO [Eleleth permits you to pass through the gate and begin your quest. . .] OAEUOEIOAEUOEI

I stubbed out the cigarette, intrigued.

Loved this the first time I read it. So glad you brought it back!

Whooaa this is a cool. The idea of texts being coded and hidden in the books of a library is so great