The Invisible Library of Kafr Musa: Part 3

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

On the morning of 27 April 1964, I took the trolley from Cairo’s Queen Farida Square to Al Azhar to meet the man I hoped might shed light on the fate of my former Arabic instructor, Professor Sami al-Ghali. Many years later I would return to Egypt, by which time the only trolleys left in the country would be those in Alexandria plying the dusty tracks between Mansheya and El Raml (beneath a web of sparking wires and a cloud of diffident nostalgia).

I was the only woman in the car, the only foreigner for that matter, and a man made so bold as to address me lasciviously in the local dialect.

“Taddi ‘ah,’ ya wardah.” (Just say yes, my rose.)

“Tuzz feek,” I replied.

“She told you to piss off!” his friend repeated, and the two erupted into throaty laughter, which spread like contagion to the other passengers. The conductor was so caught up in the general hilarity of the moment that he recounted to each person who boarded what the pretty khawagah (the Christian foreigner) had said “to that jackass, Abu Faisal,” whose own smile began to fade with each retelling.

It was the day after the Muslim Feast of Sacrifice (Eid al-Adha), commemorating the ‘aqidah—an Arabic word referring not only to the “binding” of Isaac upon the sacrificial altar, but to Abraham’s “binding contract” (or Covenant) with God. Since goats were infinitely cheaper in Egypt than sheep, they had been slaughtered in untold numbers over the past three days and their carcasses were still heaped in the alleys.

From the comfort of my hotel room, I had gazed down upon the fellahin dragging the goats by the horns from their pens to the men in the blood-drenched galabiyahs with their skinning knives who were stationed at every corner. Once the fatal cut had been administered, the animals rolled over, legs quivering and extended, as the blood flowed from the wound, trickling down the brick sidewalks and pooling in the streets.

For some reason the spectacle had called to mind an incident from when I was a little girl, during the Moscow bombings in WW2. There had been several young boys from our neighborhood, some as young as twelve, who had been training in the muddy park outside our tenement building in preparation for their being sent to the Western Front. The women in our block were tasked with feeding them.

My mother and I were preparing pots of cold soup. (We had no fuel for fire.) The sirens sounded and we crawled under our small kitchen table. When the bombs ceased and our building no longer shook, my mother crawled out but told me to stay put. She looked out the window and groaned: “Don’t go outside, Yulia. The heads, guts, and limbs of those beautiful boys are everywhere.”

I stepped down into the street. The conductor waved and laughed, clanging the trolley bell thrice as he drove off. There was still blood in the grooves of the tracks, which was cast up in gory fans on either side of the car as it continued on its merry way in the direction of Cairo’s medieval cemetery, the Qarafah, more commonly known as the City of the Dead. To this day when I dream of that jolly trolley-man, he sometimes assumes the qualities of a grim-visaged Charon.

The din of Al Azhar assailed my ears but was overlaid by another sound, the voice of Umm Kulthum, the Kawkab al-Sharq (Star of the Orient). This was because every radio in every shop and home was playing her latest song, Inta Omri (You Are My Life), which had been released a few months prior. The lyrics, composed by the poet Ahmad Shafiq Kamil, were striking in their unaffected poignancy:

Before my eyes beheld you, all they had ever known was a lifetime wasted.

For three years I had been living in Egypt. But this was my first visit to Cairo. . .

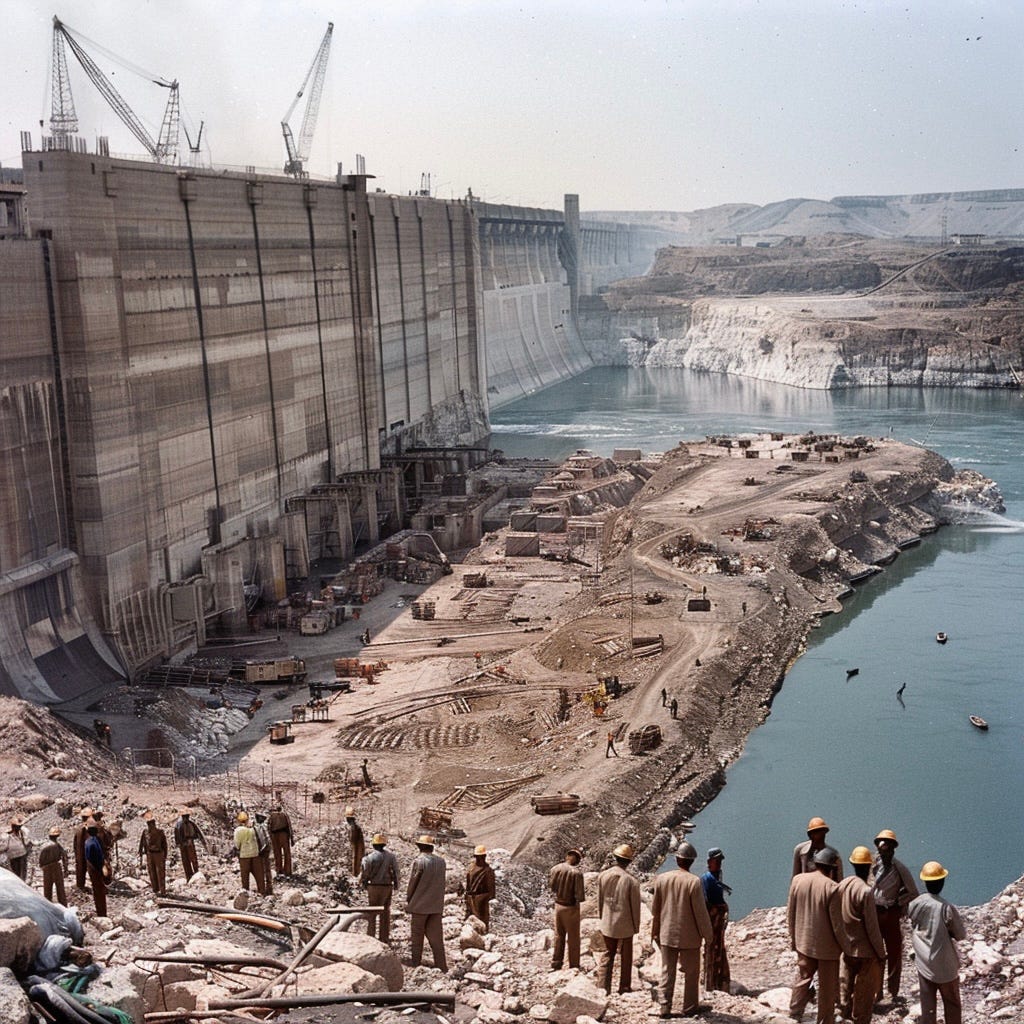

I had been working in Aswan for the Moscow-based Institute for the Planning of Hydroelectric Power Stations (Gidroproekt for short). I was an Arabic-Russian interpreter for the Egyptian and Soviet engineers involved in the construction of the Aswan High Dam. Most of my working day was spent in a quonset hut located at the bottom of a rocky basin, which would soon become the bed of Lake Nasser.

The living conditions were spartan, but I found them to my liking. We slept and supped in tents and ramshackle trailers beneath the massive cranes and concrete walls. While working there, I met and fell in love with a gifted mathematician from Stalingrad, a city which had only recently reverted to its original name, Volgograd, a fact that even my lover, Vasily, was still getting used to.

We rarely ascended the ramps and stone-cut steps leading out of the basin, since our food and other necessaries were carried down to us by locals, many of whom were Nubians, who worked at the site for months at a time before collecting their wages and returning to their villages in the swamps and mudflats along the Cataracts of the Nile. Scores, if not hundreds, of these villages would vanish like Atlantis when the flood waters came. The Nubians who worked for us did know that they were building the beast that would devour their ancestral homeland. But being ignorant of East African geography, I did not know this either.

In early April an Egyptian messenger in buff jodhpurs knocked on the door of my hut. When I opened it, he handed me an envelope, clicked his heels, saluted in the British manner, and left. The envelope contained a cable from our embassy in Cairo. It stated that Soviet Premier Nikita Kruschev had been invited by President Gamal Abdel Nasser to Egypt to attend the ceremony of the diverting of the Nile, which would take place in Aswan sometime in mid-May.

I told Vasily about it as we sat tête-à-tête over a chessboard in the recreational tent after dinner. Outside, the western sky was filled with the colors of twilight. The stars in the east had begun to rise.

“Why do they want you to go to Cairo?—Check.” He tapped the game clock.

“They want me to be on the tarmac when the Gidroproekt delegation arrives. They are arriving separately as part of the advance party. My ticket from Aswan to Cairo and my food and lodging while in the capital will be covered by the Egyptian government.”

I made a careless move and hit the clock button.

He sighed. “Mate.—You wanted to lose.”

“I never wanted to win. There’s a difference.”

He pushed his wire-rimmed glasses up the bridge of his nose. “But you are getting the knack of the game. It’s taking me more moves to beat you. I know that were I to go easy on you, you would sense it. You have a gift for rooting out deceptions.”

“You deceive me now,” I quipped.

He plucked the pieces off the board when he realized the evening’s entertainment was over. “I think it’s wonderful.”

“What?”

“What they’re asking you to do.”

“They’re not asking me. They’re telling me.”

“Your accomplishments have obviously been noted at the highest level.”

“They want me to accompany the delegation back to Aswan.”

“What’s wrong with that?”

“They’re returning aboard an Antonov. I hate military planes. They make me ill. That’s how I arrived here the first time, and I was laid up for a week after.”

He reached across the table and took my hands into his. “When we return home, what you and I have accomplished here will reflect well on both of our records. We will be able to marry—to raise a family.”

“I suppose you’re right.”

“Of course I’m right. I’m a human calculator.”

The train from Aswan to Cairo is a like a refined old matron fallen on hard times through no fault of her own. It is a relic of the British Occupation. Its cracked windows have not been replaced since Farouk fled the country; the brass fixtures and grommets in the curtains have all been stolen. I had an entire sleeper car all to myself. We arrived at Ramses Station early in the morning and went immediately to the hotel to check in.

I remembered that Profess al-Ghali had a connection to the Coptic Museum. Using a tourist map, I decided to walk there—not only to exercise my legs after the overnight journey, but to experience firsthand the marvels of this city, which I had read so much about but had never seen with my own eyes.

A man pushing a handcart full of junk (broken gramophones, torn oilskins, bent candelabras) cried out, “bekiyah, bekiyah,” a corruption of the Italian phrase “roba vecchia” (vintage goods). He was not only flogging these wares, but begging the occupants of the ornate buildings he passed by to come out and pitch into his cart something old they no longer needed that he could turn into a profit.

The Coptic Museum of Cairo, while not as famous as the sprawling Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, is nevertheless impressive and beautifully curated. I bought a ticket at the counter from a Christian woman in a turban and wandered through two galleries before discovering the administrative corridor.

Hearing the measured clack of a typewriter, I followed the sound into an open door. I was confronted by a row of lattice-work mail-slots in the mashrabiyya style. I scanned these, but could not find the nameplate I sought. When I rounded the corner, a young man in a natty suit with curly black hair looked up from his typewriter and rose in agitation.

I had committed a gaffe. Whether Christian or Muslim, an Egyptian man holding a position within the government—as all the museum employees did—dared not be seen chitchatting alone with an unchaperoned lady.

“Professor Labib,” the young man called out to the bespectacled academic in the office behind him, who had just finished rubber-stamping a document.

Pahor Labib was the director of the Coptic Museum. I remembered Sami telling me that the two of them had studied in Berlin in the 1930s, and I wondered if that experience had in anyway contributed to the director’s decision to sport a brush mustache. He stepped out of the office and addressed me in French. “Bonjour, Madame. Comment pouvons-nous vous aider?”

The voice was urbane; the timbre admonitory.

It would have been presumptuous of me to respond in Arabic. But my French was rusty, so I spoke in English.

“I’m sorry for the intrusion. I’m looking for a Professor Sami al-Ghali. He came to the Soviet Union a few years back. I’m a former student of his. I seem to recall his being affiliated with this museum.”

The two glanced at each other like conspirators in an Eisenstein film. I wondered if I had misplaced an English preposition.

“Tawfiq Bey,” Professor Labib said.

“Effendum (Sir)?”

“Take the Madame to your father.”

“At your service.”

Pahor Labib turned his bland eyes in my direction but kept them fixed on the wall behind me. “Engineer Essa al-Gabaly knows the man of whom you speak. He will be able to assist you. Good day.”

Tawfiq led me to a gallery of the museum that was being prepared for an upcoming exhibit. He lifted the tarp over the door and beckoned me to precede him.

There was scaffolding everywhere. There were electricians on the ladders working on the wiring of the lights.

A man in the center of the room was shouting suggestions and mumbling imprecations when these were ignored. He wore a flannel suit and white kufiyah wrapped tightly round his scalp.

“Baba,” Tawfiq said.

When the man turned around, I saw he wore sunglasses (even though we were inside a building). But he immediately removed these, disclosing two comically bulging eyes, like the Hungarian-American film actor, Peter Lorre.

I was wearing kit-gloves, and so I extended my right hand to shake his, introducing myself in Arabic and telling him why I was here. He put the glasses back on before accepting my hand.

I spoke rapidly and confidently.

He looked at his son with a twisted smile. I assumed he was impressed by my fluency. But he held up his hand to silence me; and I could not help but feel a bit crestfallen by what he said next. “Do you speak English?”

“Yes.”

“Then let us continue in that language. Your Arabic is passable. But that harsh accent of yours and those strange Slavic catches defile the lovely lips with which you speak it.”

I looked down at my shoes. “I was wondering if you could tell me what has become of Professor Sami al-Ghali. I have not seen him for many years. I was told you know him.”

“Yes. I’ve known him since I was a boy. He no longer works here.”

“Where is he?” I persisted.

“How should I know?”

“Because you’ve known him since you were a boy.”

“Ya Rabb,” he exclaimed in frustration.

As if on cue, every lightbulb in the room popped and went out. The atmosphere became chaotic, as the workers exchanged recriminations. A skinny man cupped his hands over his mouth and called down from one of the ladders.

“Bashmuhandis (Engineer-Pasha)! The circuit’s overloaded!”

“No, you son of a shoe!” Engineer Essa said. “The connections were loose! I warned you of that!”

He grabbed his chest and Tawfiq went to him, concerned. But his father pushed him aside, because it was just part of the act. “I’m sorry, my dear,” he said, wiping sweat from his brow, “but I must ask you to leave. As you can see, I have millions of things to do.”

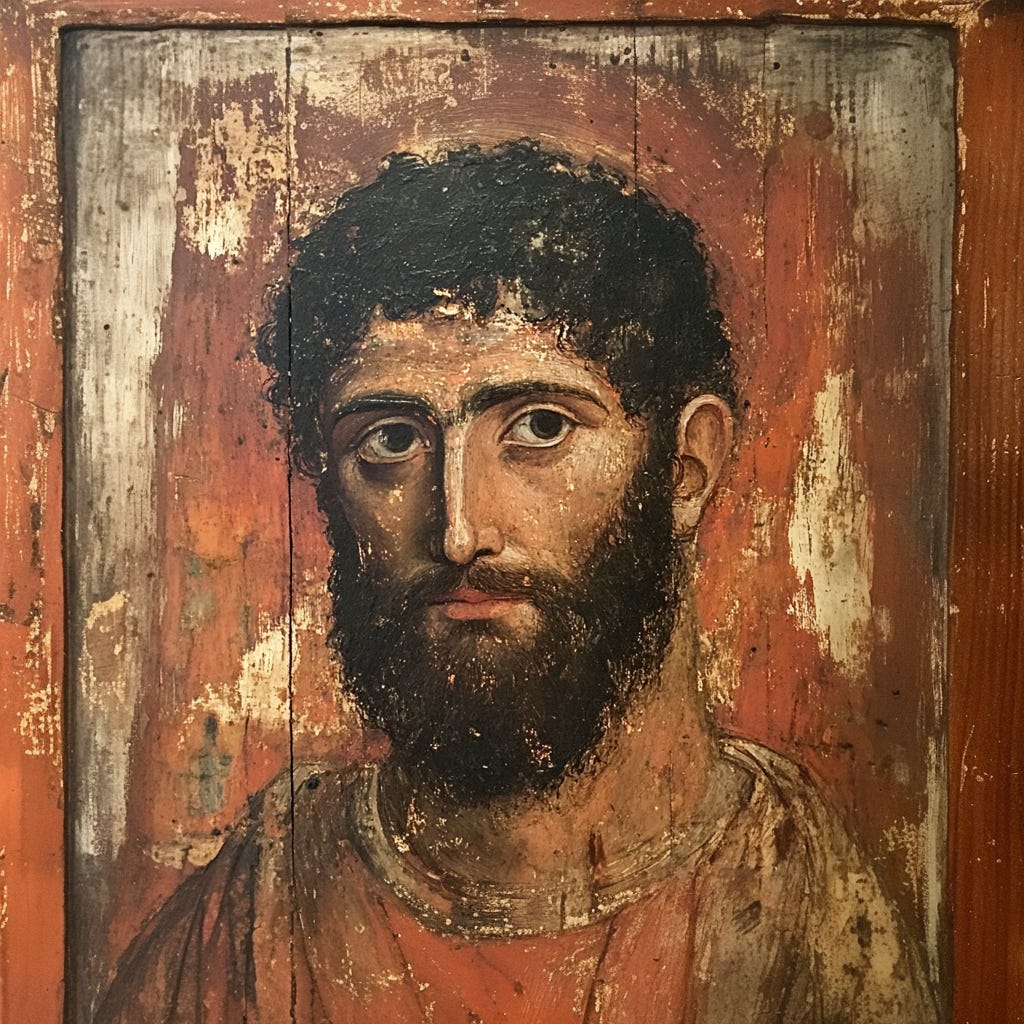

Although the lights had gone out, the room was not plunged into darkness, due to the small apertures that ran along the ceiling. A shaft of sunlight fell upon the upright lid of a Roman coffin decorated with an encaustic portrait of a young man.

I looked at it, and then again at Engineer Essa. “I wanted to ask Professor al-Ghali about his discovery.”

“What do you mean?” I could feel his eyes boring into me from behind the sunglasses.

“He told me that he had found evidence for the existence of an invisible library—hidden away in a trove of manuscripts unearthed during an excavation in the Fayyum. At a place called Kafr Musa.”

At the mention of Kafr Musa, Tawfiq walked away (pretending he had not heard).

“He spoke to you of this?”

“Yes,” I whispered.

He recoiled from me, as if what I said was too much for him to credit.

Someone entered the room, clacking a wooden mallet against a plank. It was a naqus, the ritual bell used by Arab Christians to summon the faithful to prayer. The man wielding it was Pahor Labib. The woman who had sold me the museum ticket followed the director into the room. Tawfiq and the laborers joined them before a Coptic icon (one of the museum’s artifacts), which depicted the flight of the Holy Family into Egypt.

“How long are you in Cairo?” Engineer Essa inquired.

“Until May.”

“Do you know of the coffeehouse, El-Fishawy?”

“I’ve heard of it.”

“It is near the Mosque of Hussein. I shall meet you there on Monday at noon. The Eid will have concluded and the Azhar Quarter will be alive with activity.”

“How will you find me?”

“I will find you. You are conspicuous.”

“What if you don’t come?”

“Then I will have died or lost interest. Either way, you will be in the heart of Khan al-Khalili, Cairo’s Grand Bazaar. . . There is much there to see; and there is much there that cannot be seen by the human eye.”

Without another word, he turned and walked away, crossing himself as he joined his colleagues at the icon.

It is only priests and scholars these days who can read the liturgical language of the Copts. So Professor Labib, who was leading the prayer, spoke in Arabic and opened with a verse from Hosea: When Israel was a child, I loved him; and I called my son out of Egypt.

Continue to Part 3

This story is an absolute treasure.

Fascinating!!