The Invisible Library of Kafr Musa: Part 2

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

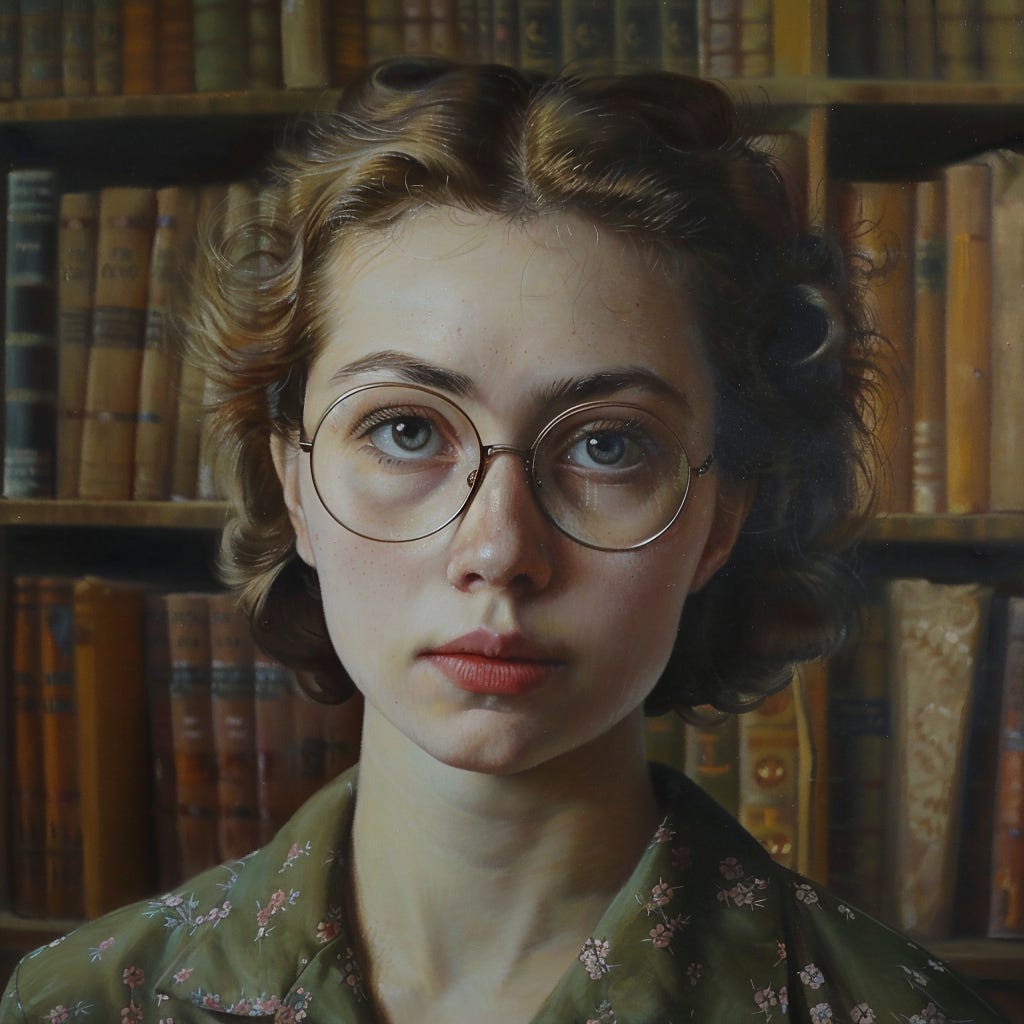

No sooner had I stubbed out my cigarette than I was drawn into Sami al-Ghali’s powerful arms. I gasped and righted my glasses to better see what I was certain would be the vision of his sensual lips closing in on mine. But the furthest thing from the Coptic scholar’s mind was a sexual fling with a student in a cheerless study overlooking the Neva amid the peripheral confusion of dust motes, foolscap, and a honking Lada in the street below.

My puckered lips morphed into those of pursed contemplation as I allowed myself to be led to a massive sideboard (or buffet) that stood flush against the damask flock wallpaper, a faded remnant of those champagne-swilling days of the Tsars. I imagined Sergeevich Pushkin in his early years pacing these very floorboards, scored and scuffed as they were by that specimen of American carpentry, which had been dragged from an outer room into this one (doubtless by a team of blasé Soviet minders at Sami’s bidding and the state’s insistence).

The sideboard was littered with photographs, butterflied books, unbound sheaves of yellowing paper, and a green-shaded lamp, which the professor snicked on in coy demure. But when no current entered the bulb, he went to his desk, struck a match, and lit a fat candle in a cheap tin dish. It was the middle of the afternoon; but the sun’s rays seeping through the smudged windows on the east side of the study had lost their brilliancy among the thickening gloom.

Through all these proceedings the professor continued to talk. He warmed to his recondite theme, which I was only half-listening to. I was more intrigued by his flamboyant mannerisms. And I wondered if it was common among Egyptian men to flail their arms as they spoke, clench their fists, waggle their heads, and look askance at the floor as if it had uttered an absurdity. Even in our drunkenness, we students were expected to comport ourselves with the blandness and poise of a grim-suited apparatchik.

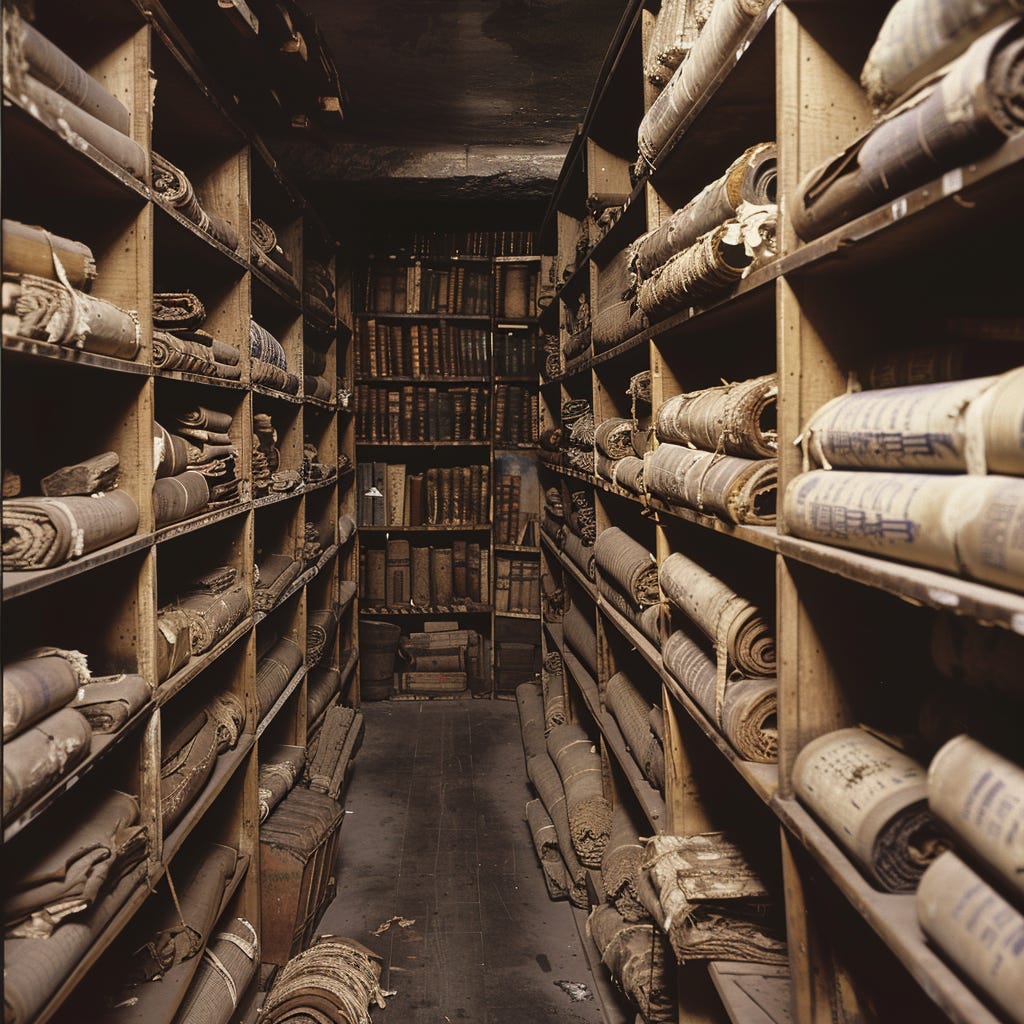

“Everything in that musty annex,” Sami exclaimed. “Everything!—the coffins, the manuscripts, the potsherds—was the property of Friedrich Wilhelm University. I knew that my time in Germany was limited and that I dare not steal these items, which now fell under the purview of the Third Reich. But labor in 1930s Berlin was cheap, and my remittances from Alexandria were substantial.

“I hired a team of photographers, former Weimar movie makers who had fallen on hard times. They assisted me in producing photostats and photographs of the manuscripts and other treasures in the annex. It was these I brought with me back to Egypt, thereby preserving in celluloid the fruits of the Kafr Musa excavation.”

My attention was drawn to a 1908 Hermitage Museum collection catalogue on the sideboard, which lay open to a page dominated by a grainy photograph depicting a chiseled idol in Egyptian alabaster of a matron caught in the coils of a serpent. The caption read: Diana enthralled by a snake. (Late Roman period)

“Was this found at Kafr Musa?” I asked.

“No.” Sami shook his head. “Damietta. It was unearthed during Khedive Ismail’s construction of the Suez Canal. That is not Diana. I have penned a letter in French to the museum to inform them of the misattribution. The serpent has a lion’s face. It is the Gnostic archon Yaldabaoth, the evil Demiurge and Creator of the material world.”

“Why is the Creator evil?”

“Because he has imprisoned our souls—the eternal light of the divine Monad—in the coils and meshes of base matter. The woman is someone we have already encountered. It is Sophia, the goddess of Wisdom, who is also Yaldabaoth’s mother.”

“So Wisdom brings forth creation?”

“So to speak. It is an allegorical sculpture. Sophia is being strangled by Yaldabaoth. The Creator, in his hubris, is destroying the Mind that created him—as a logic-chopping rationalist might ‘reason away’ the existence of God.”

I spontaneously recited the lines of an English poem we had been forced to memorize when I was a schoolgirl:

“Philosophy will clip an Angel’s wings, Conquer all mysteries by rule and line Empty the haunted air, and gnomed mine Unweave a rainbow as it erewhile made.”

Sami looked at me impressed. “You know Keats? I applaud you, habibti. You have hit on what I believe the artist’s intention to have been when he sculpted the idol.”

“How do you know the artist was a he?” I asked with a smirk, as I continued to turn the pages of the catalogue. Sami closed the magazine, annoyed, and set the candle dish on its cover.

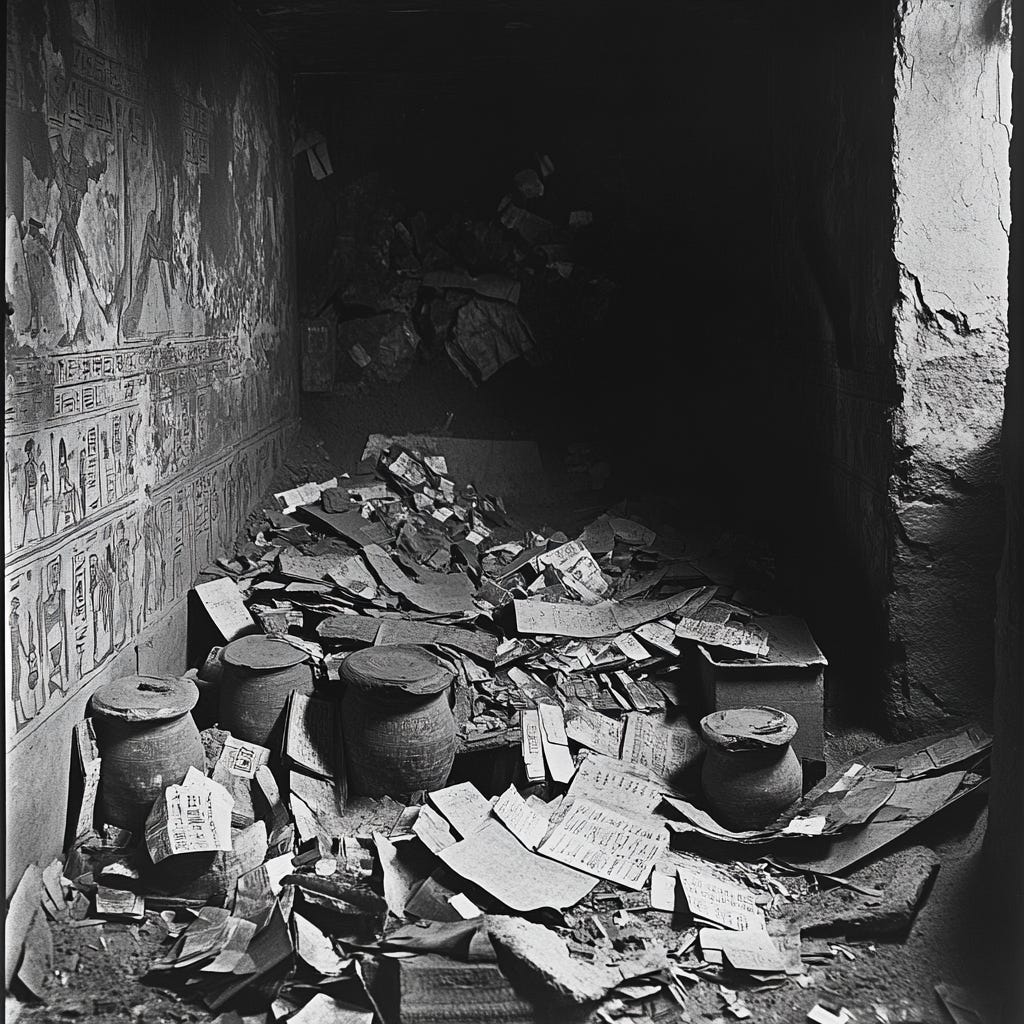

“Incidentally,” he remarked, “the Egyptologist who led the Kafr Musa expedition, Ludwig Borchardt, composed field notes, which were also in the university annex. He was not interested in the Gnostic relics, dismissing them as ‘proto-Christian rubbish’. His focus was on the tomb itself, which dates to the time of Pepi II.”

Sami placed his fingertips on a slender buckram-bound tome. “This is a working draft of what will be the first fascicle of a seven-volume study of the invisible library of Kafr Musa. A few years ago I built a private press at my family’s izbah (country estate) on the outskirts of Borg El Arab. I do not trust the printers and compositors of the Boulaq Press in Cairo.”

I opened the folio and perused it. Some of the pages were typed; others were handwritten. The bottom of each page contained a running commentary and critical apparatus. There were corrections and marginalia throughout.

Sami contemplated the candle flame. “Once I discovered the gateway into the realm of Domedon Doxomedon, I no longer cared about the contents of the individual scrolls and codices in the annex. From then on, I dipped into them only to look for those clusters of Greek and Coptic letters which form the interlinkages between the separate works of the library—totaling 125 books: hymns, poems, prophecies, etc. But these individual books can only be read in a serial fashion, since the last sentence of each contains the title of the next. . .

“I could live ten lives,” Sami mused. “Ten lives!—and would not have enough time to publish a critical edition of each manuscript in the university’s annex. That is a task that will have to be left to future generations. My job is to shed light on the secret library that has been artfully bundled up and metaphorically compressed into that gouged-out lacuna in the coffin of the Gnostic goddess Sophia.”

I leafed through the pages, glancing at the footnotes and interlinear translation, both of which were in English. I knew neither Coptic nor Greek. But even in translation the narrative was inelegant and rambling. The meaning of the words were clear enough. But just because words have meaning does not imply they have purpose. There were nonsensical passages such as the following:

The Seeker wanders through the silent spaces hidden between the words, drawing nearer and nearer to the Pleroma, even as he recedes from it.

I skipped over three of the so-called ‘books’ only to find a variation on the exact same theme several pages later:

But the Pleroma, too, wanders the vacuum in quest of the Seeker, drawing nearer and nearer to him even as it recedes from him.

I recognized the name Yaldabaoth (the Demiurge) in a paragraph that would take on chilling significance many years later when the completed first fascicle was given to me as a parting gift:

Just as Yaldabaoth created this world of matter, so too did he create the unseen books the Postulant believes he is reading. But Yaldabaoth shall unmake what he has made, leaving the Seeker blind before Metanoia, Mother of Repentance, and her sister, Sophia, enthroned side-by-side in the Pleroma.

“Are there other lacunae?—Other gaps in the library?” I asked innocently.

The question upset him. “Of course there are!” He snatched the folio from my hands. “It is unavoidable.” He flipped to a page spangled with bracketed ellipses to make his point. “Some of the manuscripts are illegible, others have perished. But the omissions do not detract from the importance of the discovery.”

I could tell by the glow in eyes that there was another revelation he was eager to impart to me. “Last night,” he remarked, “I found the final piece of the puzzle, the linchpin that holds the machine together.”

He reached for a photograph of a torn papyrus scrap. For my benefit, he scribbled on a notepad a transcription and translation of a blurry section of the papyrus, which included another word or phrase that had been intentionally scratched out:

|| The Seeker arrives at the end of his journey only to find that in the beginning was the AAOO [. . .] OOAA || OAEUOEIOAEUOEI.

He wiped his face and smiled triumphantly. “The last sentence is in Demotic Greek. If my theory is correct, I have discovered the earliest extant fragment of the opening words of the Book of John.”

I confessed to him that I had never read the Book of John. He was incredulous. He shook his head and recited it to me. “In the beginning was the Word.” He pointed to the text. “That is the Greek definite article ho, which is masculine—the same as Logos (Word). You will recall that the lacuna in Sophia’s coffin had a string of Coptic vowels to the left of it, and the same string reversed (in palindrome) on the right. Yulia, this is the last sentence of the invisible library. But the last sentence itself contains a lacuna. It’s all so extraordinary! Don’t you agree?”

When someone fishes for a compliment from me, I become embarrassed and tend to say exactly what I am thinking, which does not always come out right (especially when I am speaking English). “Which of your discoveries is the more important one, Gospodin Professor? The invisible library? Or this unconfirmed Biblical passage? It’s all so confusing. But then I was never good at acrostics.”

His shoulders slumped and he became downcast. I had spoken out of place. He would never be able to look me in the eye again. I was devastated.

“I return to Egypt in two months,” he said in a hollow voice. “Once there, I shall present my findings to my peers at the Coptic Museum in Cairo. Herr Borchardt’s notes lead me to suspect there is a chamber beneath the dais where Sophia’s coffin was found. I will call on the Egyptian government to sponsor a new expedition to the village of Kafr Musa in the Fayyum. I have pored over every line of every manuscript in the annex. But I cannot locate the missing ‘Word’—the Logos—which I am sure lies between the Alpha and Omega.” He touched the lacuna on the notepad. “My work is not yet done.”

I left Sami’s apartment in tears. After that day, he refused to meet with me in private. I would never have the opportunity to apologize. In the painful weeks that followed, he lectured us with an air of highhanded detachment. And when the term ended, he was gone. His replacement was a Tajik schoolmaster, who had learned Arabic from his Muslim parents before their death during the Revolution.

One morning, Professor Alexander Guber, head of the institute, entered our classroom with his assistants. He asked me to rise and read aloud a letter that Sami had written shortly before his departure. In it he praised my fluency in Arabic and affirmed that (of all his students) I had shown the most promise. By this letter, Sami al-Ghali had all but guaranteed that I would have a respectable job waiting for me when I graduated.

I started to read part 3 and realized I had somehow missed part 2! This story is so rich with intrigue.

…amid the peripheral confusion of dust motes, foolscap, and a honking Lada in the street below. 👏🏻